The immediate impacts of the Great Chinese Famine—thousands of people resorting to cannibalism, limbs protruding from the ground due to overcrowding of graves, and millions of deaths—have been studied in great detail, largely part because of their salience and accessibility. The longer-term, more insidious effects of this famine have only been studied intermittently and without the depth that modern-day Chinese citizens deserve. Shige Song, a sociologist at Queens College of the City University of New York, has spent much of the last 20 years examining another example of slow violence: the effects of famine on pre and postnatal infants. Song has found that not only were pregnant people who were physically stressed by the famine more likely to give birth to females, but those women were also statistically more likely to suffer from infertility because of their famished mothers.

On its own, the fact that 36 million Chinese citizens died from the Great China Famine is staggering and incomprehensible. That shock is only compounded when paired with another statistic—the number of people who were not born because of the famine. The starvation resulted in a significant drop in birth rate, which meant that there was an “estimated shortfall of 40 million births in China during [the years of the famine].”1Yang Jisheng, Tombstone (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2012), 13. In total, that is a loss of about 76 million Chinese lives during a three-year period.

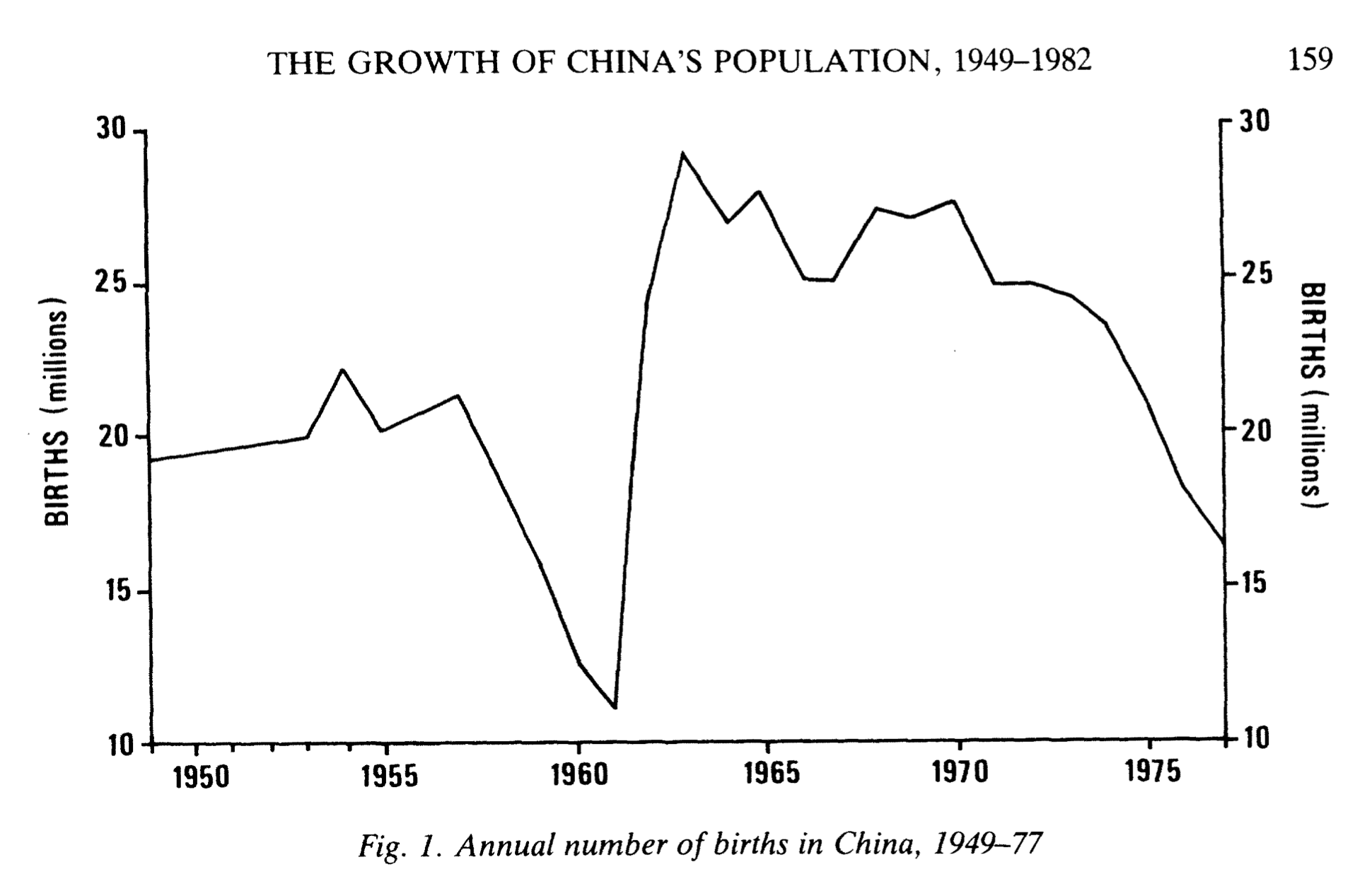

In 1957, when China stood on the precipice of famine, the average birth rate per 1,000 citizens was 34.03; in 1959, only one year into the famine, that number had dropped sharply to 24.78.2A. J. Jowett, “The Growth of China’s Population, 1949-1982 (With Special Reference to the Demographic Disaster of 1960-61),” The Geographical Journal 150, no. 2 (1984): 158, accessed December 20, 2020, https://www.jstor.org/stable/634995. Unsurprisingly, the average birth rates for the years 1960 and 1961 do not exist. However, given that the famine was in full force during those years, it is completely reasonable to assume that the number of births remained similarly low.

Although one would assume that the ratio of males to females born would decrease equally during the years of the Great Chinese Famine, that was not the case. During and up until two years after the famine, the ratio of male-to-female births skewed significantly towards females. In 1957, 52.74% of children born in China were male; in 1962, at its low, 51.60% of children born in China were male.3Shige Song, “Does Famine Influence Sex Ratio at Birth? Evidence from the 1959-1961 Great Leap Forward Famine in China,” Proceedings: Biological Sciences 279, no. 1739 (2012): 2889, accessed December 20, 2020, http://www.jstor.org/stable/41549364. A shift of about 1% in birth rates is very statistically significant and not within the bounds of average male to female ratio fluctuation. After the famine, beginning in October 1963, there was a compensatory rise in male birth rates, resulting in a V-shaped graph of the percentages of males born in China during the late 1950s and early 1960s.

The theory of adaptive sex rates proposes that the ratio of male-to-female children born is variable and shifts depending on the health and well-being of the mother. This theory states that “because the reproductive success of male offspring tends to be more variable and resource-sensitive than that of female offspring, parental investment in sons of good quality yields greater reproductive returns than the comparable investment in daughters of the same quality, whereas parental investment in sons of poor quality yields lower reproductive returns than the comparable investments in daughters of the same quality.”4Song, “Does Famine Influence,” 2883. This quote implies that, during times of physical or resource-intensive struggle, pregnant people are more likely to give birth to women, as females have higher rates of success in resource-deprived environments. The statistics provided above with respect to male birth rates during the Great Chinese Famine give merit to this theory, as the ratio of males born dropped while mothers were in strife and rose once those mothers physically rebounded.

Intriguingly, the adaptive sex rates theory maligns with another significant, long-term impact of the Great Chinese Famine—the adverse impacts of in utero exposure to famine on fecundity. Famine can cause brief periods of infertility in women, for “when food consumption falls below a critical minimum level, women stop ovulating and thus cannot conceive.”5Shige Song, “Assessing the Impact of ‘in Utero’ Exposure to Famine on Fecundity: Evidence from the 1959-61 Famine in China,” Population Studies 67, no. 3 (2013): 293, accessed December 20, 2020, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43287890. Once food consumption surpasses that critical minimum, however, ovulation is restored.6Song, “Assessing the Impact,” 293. But if an already pregnant woman’s food consumption drops below that critical minimum, scientists hypothesize numerous deleterious impacts on the fetus, specifically pertaining to “in utero development of the organs responsible for the production and regulation of reproductive hormones.”7Song, “Assessing the Impact,” 293. The Great Chinese Famine presents a perfect disaster in which to examine this hypothesis, as millions of children were conceived and born during the three-year period.

Through extensive research, Shige Song found a strong positive correlation between in utero exposure to famine and infertility in women. Chinese women whose mothers were famished between the years 1959 to 1961 have an increased risk of sterility by 1.1 percent, and “given that primary and permanent sterility is a rare phenomenon with an overall population prevalence of only slightly higher than 1 percent in China, this is a substantial and important effect.”8Song, “Assessing the Impact,” 304-5.

When paired with the increased percentage of women born during the famine, Song’s research regarding fecundity highlights the long-term, disastrous impacts of the Great Chinese Famine. The Great Leap Forward brought about the death of 36 million Chinese citizens and the shortfall of 40 million more citizens being born while simultaneously increasing the percentage of women who were born during the years of 1958-1963. And those women had a significantly higher chance of being born with lifelong infertility due to their mothers’ lack of access to proper sustenance. Not only did the Chinese Communist Party bring about incomprehensible loss to its citizens during the Great Leap Forward, but its long-term fallout continued to differentially impact women for decades afterwards.

Figure 1,9Jowett, “The Growth of China’s,” 159. Figure 2.10Song, “Does Famine Influence,” 2888.