Amidst Friday’s grab-bag of cultural material, the Pussy Riot video stood out the most to me, especially since it is so contemporary. By combining anti-Putin, LGBT, and feminist sentiments, the band was arrested outside of a church for asserting their beliefs.

I think what interested me most is that this protest highlights the tyranny of Russia for certain people that still exists today. In this class, we have read many texts and seen films depicting the struggles people have faced in exile, indoctrination, censorship, and countless other contentions. However, this riot is bold and courageous; though there is something deeply upsetting about seeing people having to go to extremes for equality (whether that be for women, queer people, etc.). Invoking God and, interestingly, the Virgin Mary as an icon for women, a savior, an insider, Pussy Riot dares to cause a storm in a country still struggling.

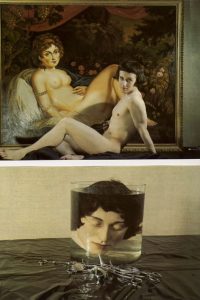

I found the parallel between Pussy Riot and the New Wave art, namely Chernyshev’s History of a Love, fascinating. Feminism in the culture we have studied has been present, but preliminary. This painting struck me. As Pussy Riot protested, Chernyshev painted a stark comparison, with a past female, idealized, glowing, perky… With a modern woman posing next to an antiquated portrait, emotions rise — do you love her for being different? For being herself? Or do you hate her for being different?

The second half of the painting is strange and alarming, (and I could be totally wrong), but demonstrated to me the desire to pick and choose the parts society maintains of a woman.