And so, draped in red, the pendulum swings back again. We have often discussed the semi-cyclical (ovulalular? Parabolic? Any shape that implies recurrence will do) nature of cultural change (and, hence, its representation in cultural production) in Russia and the Soviet Union. We read Gladkov’s Cement, in which Gleb arrives home from the front to find everything (especially relations with his wife) radically altered. Gleb struggles to comprehend the new, radical gender relations of the (albeit heavily idealized) Soviet world- his wife operates outside the home, holds responsibilities. He is not the center of her world, and he bristles at his loss of authority.

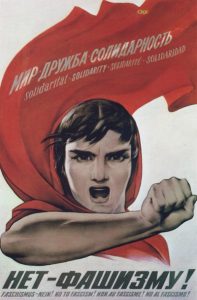

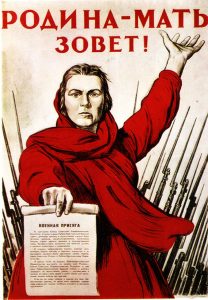

Then comes Stalin, and the dynamism of the early Soviet gender ideal is locked behind the iron facade of towering, epistemologically stable gender monoliths. Enter ‘red traditionalism’- man as warrior, man as worker, woman as mother. Mother calling for revenge, raising pioneers, etc.

So what to make of the gender roles portrayed in Moscow Does Not Believe in

Tears? This is a big topic, so I will say just a few words here. Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears appears to be a sort of synthesis of the two previous models for gender relations (and their portrayal) in Soviet works. Ekaterina is the director of her factory. This is portrayed as an achievement (she is complimented, remarked upon), but essentially normalized: her life story remains within the realm of the possible. It is just unusual enough to be a source of dramatic tension with Gosha-this dramatic tension is not employed in the movie to ‘prove’ Gosha ‘wrong’, or to ‘prove’ his patriarchal views ‘right’ (at least explicitly.) Rather, it lets these views be showcased, and also normalized. ‘Red traditionalism’ is given a platform, and is left unquestioned. When Gosha is a ‘strong father,’ the results are shown as positive, and when he asserts patriarchal control, Ekaterina acquiesces. He leaves, upset, when he finds out about her position, but returns with the ‘problem’ left unresolved: drunken comradeship and zakuski, deus ex machina that they are, do not change that Ekaterina is still the director of her factory. The ending is touching, but has a note of ambiguity-Soviet gender relations continue to toe the line between progressivism and traditionalism.

But everyone seems happy. And it really is a beautiful movie.