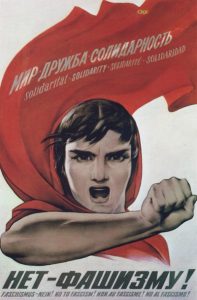

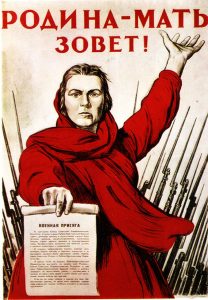

Looking at the Stalin-era propaganda posters, the personified, female Motherland (Rodina-Mat’) appears again and again. She is portrayed in a more or less uniform manner-she is swathed in a red approximation of village female dress, and she occupies the center of the poster, either calling upon the viewer directly, or looking up and leftwards towards a hostile ‘other’ (it is up for debate whether the figure in the V.S. Ivanov poster is the Rodina-Mat’ ‘simplified,’ or a different figure, an archetypal Soviet all-mother.

The personified Motherland demands two things: action from the viewer, or damnation upon the other-enemy. This action is tied with issues of war, betrayal, revenge- this action requires either violence or self-discipline as ‘verbal violence’ (nye boltai!). The viewer is expected to do something, to placate this figure, to prove themselves a real Soviet citizen (though, keeping Freud in mind, this mother-invocation to go fight and save the motherland might have slightly different implications for young Soviet men…). The Rodina-Mat’ is the ‘mother’ to all citizens, the home front conscience who spurs them on. She will harvest the grain, clutch the child, but none of this will be possible if the viewer does not act.

So, where’s dad? The figure that is missing from these posters is, of course, Stalin himself. This does not mean that he is absent from Soviet propaganda posters- the difference, rather, seems to be in his role. A cursory search reveals that, in Stalin-era propaganda posters, the role of Stalin himself is, compared to the Rodina-Mat’, markedly less aggressive and action based: he is an object of adulation, a benevolent guarantor of the future. When he is ‘doing’ something, he is portrayed as insulated from the viewer’s gaze: they will see how he acts, but he does not explicitly call upon them to act.

Why is this? I posit that, in the Stalinist symbolic universe, Stalin-as-image and the Rodina-Mat’ are two components of a symbolic ‘pair,’ a semi-parental function with a dialectic relationship both to each other and to the viewer. As an image that represents, to a certain degree, a ‘real’ figure, Stalin-as-image cannot be too intimately tied to the world of direct action: as people disappear in black cars at night, and gossip from the front varies in its positivity, this image might not be as convincing. The Rodina-Mat’, however, is doubly useful: she simultaneously does not ‘exist,’ yet, as a reimagining of the ‘eternal mother/feminine’ figure, exists everywhere, and retains real power to motivate. These two figures, hers and that of Stalin, need each other to comprise a full symbolic universe: she to demand love in the form of action, he to receive love as the result of implied action.