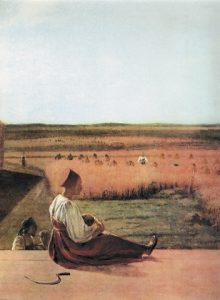

Alexei Venetsianov, was the first and the single one of his Russian contemporaries to find inspiration in the Russian countryside and in its landscapes and inhabitants. In contrast to Russian painters like Karl Briullov and Sylvester Shchedrin, who seem to have lived in Italy for most of their professional lives and were so heavily inspired by its influences that their identity as Russian painters vs Italian painters seems contestable, Venetsianov glorifies the seemingly simple and pristine peasant way of life. With him, we see this shift of focus from the exterior and foreign towards Russia and its distinctness, which gives way to feelings of nationalistic pride on the part of the painter. In my mind, this is exemplified in his Spring, Plowland, and in his Summer, Reaping:

In these two paintings, the idea of simplicity is very prominent: there is little to no action occurring in the two works, eschewing a certain sense peace and serenity. The colors are very light and the sky is blue and very clear; although depicting scenes of hard manual labor, the scenes are very lighthearted.

Another observation to be made in this depiction of peasant life, is the tying together of the traditional garb of the peasant to the season: the spitefulness of the pink in spring, and the heaviness of the red in summer. Venetsianov in his paintings shows the strong relationship of the Russian peasant to nature: the peasant’s ties to Russia and its nature becomes an essential part of the Russian peasant cultural identity through the eyes of the painter.

However, the depiction of the Russian peasant in these paintings is incomplete. In attempting to portray the peasant life in his paintings, Venetsianov shows his disconnect to the Russian peasants and their culture, depicting only a superficial ideal of the peasant life. This can be first seen in the way he paints the peasant maidens, though in traditional garb, they are painted in a style strongly resembling neoclassicism; especially in Spring, Plowland, where the form and movement of the maiden is reminiscent of those found in other neoclassical European paintings. The disconnect is further exemplified in the simplicity of the peasant life depicted. When I first listened to the peasant’s folk music, when I read the folktales, and when I first saw the traditional folk dancing, I was struck by its prevalent vivacity and variety; there was nothing simple and peaceful, in the literal sense of the word. Nowhere can we see in these paintings this underlying passion for life that manifests itself in beautiful harmonies, at times full of life and energy and sometimes beautiful and haunting, nor can we see the rich and colorful imagery of the peasant’s folklore.

The confusion surrounding what it means to be truly Russian is again manifested in Venetsianov’s paintings, where he is still too influenced by Europe in his art to perceive or depict a truly distinct Russian identity.