As we consider Russian folk culture as reflected in Russian high culture, it is important to keep in mind the roots from which this ‘folk culture’ (whether authentic or reworked, presented or constructed) springs. What does the life-world of the Russian peasant look like? From what components is it constructed, and how do these components syncretize into a ‘folk culture’ ? Village culture would, naturally, center to a degree around the izba, the peasant hut. To draw a direct link between spatial features of the izba to the manifestation of folk belief in high culture is too big a jump, but I do think think that elaborating on a few aspects of the izba could be useful here.

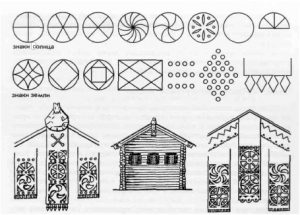

Let us begin by looking at two sets of illustrations, that of the ‘signs’ (znaki) inscribed onto Russian peasant houses, and that of the doorway decorations. The znaki are divided into two types: signs of the sun, and signs of the earth. The motive behind decorating peasant houses with such signs can be guessed at: the symbols link the houses (and thus the peasant families living within them) both to pre-Christian beliefs surrounding the sun and earth (remember the Ukrainian Easter egg?), and, more directly, to the agricultural rhythms of village life: without sun, without earth, there is no harvest.

The effect of such symbols upon ‘folk culture’ as such, and its distillation into forms for consumption and reproduction in the form of ‘high culture’, should not be ignored. What does it mean that the lifeways of the Russian peasant are inscribed onto where he lives (which, followingly, is both the space in which he is imagined and the space from which he signifies his ‘essence’)? The izba becomes a multi-layered symbol: a place of residence, yes, but also a piece of ‘folk art’ signifying agricultural ties and a shrouded pre-Christian legacy.

The doorways, the physical entrance point to this ‘signifying’ space, are themselves covered in signs: chickens, the sun-the pre-Christian/agricultural vocabulary stays the same. Entering the izba, the peasant is reminded of the rhythms that structure his life, while the writer or artist passing or imagining the izba is reminded that there are proscribed symbols and rhythms linked with ‘folk life’. ‘Folk culture’ is given architectural unity in the form of the izba, thus creating a building block from which ‘high culture’ can begin to construct the image of the peasant village (and from there incorporate the song, the dance, the peasant himself, into a unity of allusions).