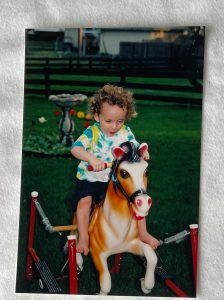

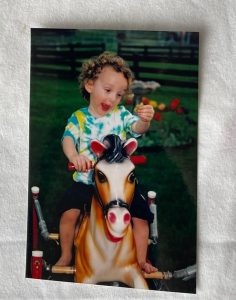

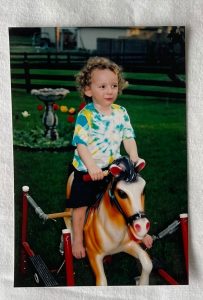

The conceptualization of this project immediately triggered questions about patient confidentiality. How could I depict my clients while keeping their identity and personal information present? How could I honor them in this work without their exploitation? Such questions required critical examination of the subjective lens through which I viewed my clients. By working with families, I viewed the client in the role of a patient, but also as a brother and son. The idea of client identity deeply inspires my work as a therapist and healthcare advocate. How did personal connections influence my work and experience as a therapist? To convey my subjectivity and protect the identity of my clients, I will use images of my brother from ages 3-5 as reference images for my artwork. Per the sociological imagination, this artistic decision reveals the deeper impact of personal biography. His images convey subjectivity’s role in inspiring a deeper connection to work or acting as a distorting lens that confuses sociological inquiry.

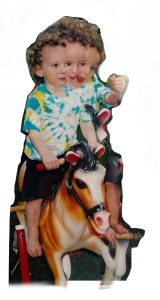

To explore the methodology of this work I expounded upon three specific images taken of my brother at age 3. These photographs evoke a sense of rocking-like motion that I was interested in studying. Translating this image into a drawing, I focused on creating colorful, shifting visuals to express neuroscientific research describing how the hyper-stimulation of neural networks contributes to sensory overload and stimming behavior. Markam and Markram’s (2010) Intense World Theory The authors offer hyper-functioning local neural microcircuits as a potential biological mechanism of autism. Through this model, hyper-perception, hyper-attention, hyper-memory, and hyper-emotionality connect to memory and emotional states. Specific molecular cascades contribute to hyper-reactive, hyper-plastic, and hyper-functional microcircuits in autistic brains. I cannot fully convey the experience of stimming without lived experience. Using this biological and advocacy autism research as background I created this piece to convey my mental exploration of this topic as a non-autistic individual.

Using photoshop, I created an image emphasizing the body’s movement in space and time. Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behaviors, interests, and activities comprise the third diagnostic domain of autism spectrum disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Stimming describes repetitive behavior such as hand flapping, body rocking, object manipulation, or vocal stereotype (MacDonald et al. 2007).

During my time as a therapist I frequently viewed stimming in the form of lining up similar, but different colored, objects such as toys, play dough containers, or alphabet puzzle pieces. Children might become fixated on such forms of play-based stimming and resist redirection to other activities. As an ABA therapist, stemming was framed as a behavior to decrease through behavior redirection and operant conditioning techniques. At the same time, I frequently used repetitive physical motions such as rocking a child or jumping with them on a trampoline as a way to foster connection with the children I worked with. Such reinforcement was physically exhausting work that required me to hold, lift, and rock a child. I hope to translate this physicality into my artwork in later weeks. The nuance of downregulating stimming while also using similar behavior as a reinforcement illustrates the ongoing debate over stimming within the Autism community. In her artistic video “I Stim, Therefore I am”, an Autistic self-advocate and professor of English Melanie Yergau redefines stimming as a valuable language form (Yergeau 2010). In presenting stimming as an expression of identity-based communication, Yergau stands in defiance of the pathologized ABA framework. In future weeks I hope to explore how Yargau and other Autistic self-define and depict the experience of autism. Going into next week, I want to record the redefinition of stimming over time and how the definition presented within the field of ABA might contrast with that of Autism advocates.

References

MacDonald, R., Green, G., Mansfield, R., Geckeler, A., Gardenier, N.,

Anderson, J., … Sanchez, J. (2007). Stereotypy in young children

with autism and typically developing children. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28, 266–277.

Yergeau, M. 2010. Circle wars: Reshaping the typical autism essay. Disability Studies Quarterly

30 (1). http://www.dsq-sds.org/article/view/1063/1222. Accessed 28 Dec 2014.