Integrating Special Collections & Archives into learning experiences offers the opportunity to get hands-on with books, manuscripts, and archival records: the raw ingredients of history and how we’ve interpreted the past across time.

Grounded in the Primary Source Literacy Guidelines, the education program of Special Collections & Archives emphasizes active learning for information, archival, and visual literacy.

There are infinite ways to integrate special collections materials into a classroom experience, whether exploring examples of printmaking techniques, transcribing nineteenth century correspondence to use as mapping data, or investigating the dissemination of a work of literature through the ages. The intersection of distinctive materials and intentional pedagogy offers an exciting space for collaboration. The participants in the NEH Seminar Teaching the Holocaust through Visual Culture engaged with four artist’s books and publications:

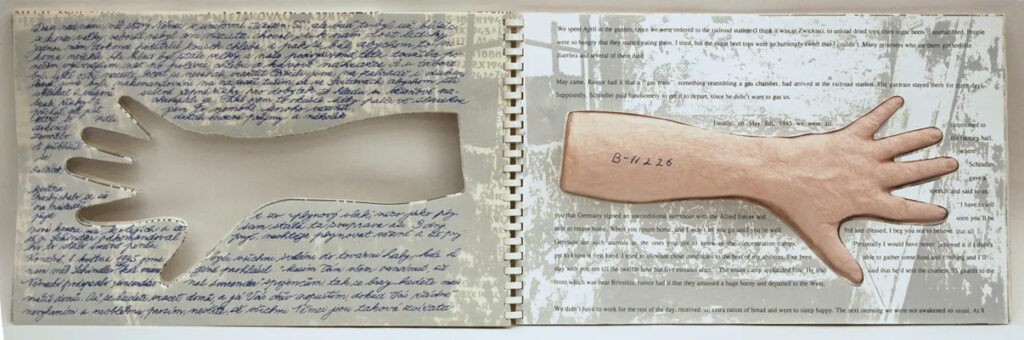

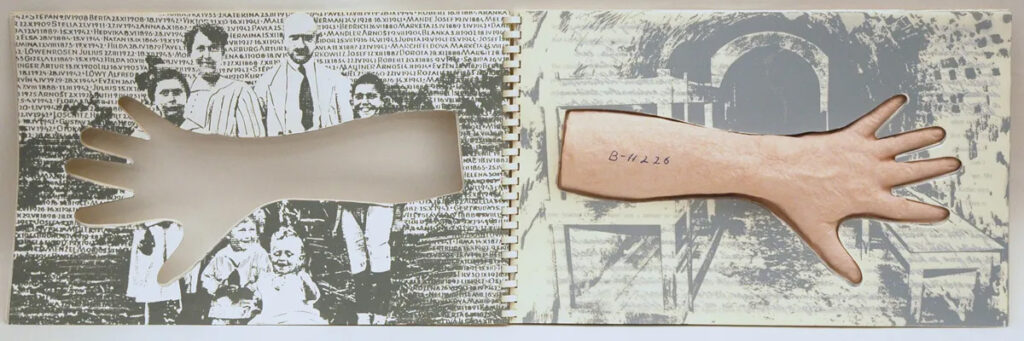

- Tana Kellner’s B 11226, Fifty Years of Silence : Eugene Kellner’s Story. Rosendale, N.Y: [Women’s Studio Workshop], 1992.

- Tana Kellner’s 71125, Fifty Years of Silence : Eva Kellner’s Story. Rosendale, N.Y: [Women’s Studio Workshop], 1992.

- Two volumes preserving the author’s parents’ memory of internment in several concentration and extermination camps during World War II. Handwritten Czech text, transcribed into English by the author, is printed over contemporary and historical photographic images from concentration camps. The original manuscript is reproduced on transparent interleaved pages. Family photographs provide a poignant contrast to these horrific accounts. Die cut pages fall around a flesh colored, handmade paper cast of each parent’s forearm, tattooed with its ineradicable number.

- Art Spiegelman’s Maus: a Survivor’s Tale. [New York, NY: Raw Books], 1980.

- Spiegelman first published Maus in parts issued as inserts of Raw, v. 1, no. 2-7 (1980-1985), a comics anthology he co-produced—the format of these parts is much more reminiscent of an ephemeral comic book and offers an alternate reading experience and glimpse into the evolution of the graphic novel.

- Maureen Cummins’ Unpublished Manuscript, 1946. Translated by Gertrude Weaver. Rosendale, New York: [Maureen Cummins], 2019.

- Produced at the Women’s Studio Workshop, Rosendale, N.Y., in the summer and fall of 2019 by Maureen Cummins as part of the Friends, Peace, and Sanctuary project. The original manuscript was translated from the German and compiled by Gertrude Weaver and her students at a German-language secondary school in Pennsylvania. Weaver shopped the manuscript to U.S. magazine publishers under the title “Buchenwald experiences of Hans Bergas written for Chester High School students, 1914-1946”–with no luck. It was eventually published in the book Fighting fascism and surviving Buchenwald: the life and memoir of Hans Bergas / by Bension Varon (Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, [2015]).

This collection of materials allowed participants to explore the pedagogical impact of close-looking and sensory experiences by engaging with Holocaust narratives in the artist’s book format. Artist’s books, as book and art objects, encourage us to think broadly about how we experience narrative and receive information.

Introduction to Artist’s Books video:

Read more about ways to integrate books and other primary source materials (whether physical or digital) into meaningful learning experiences on SC&A’s education site. The Teaching with Primary Sources Collective also offers various entry points for considering the pedagogical and practical aspects of working with sources.