I cannot remember a time when there were not stacks of photos, albums, bins, and scrapbooks out in the house somewhere that my mother was in the process of going through. For many years there was a goal of “finishing the scrapbooks,” an unachievable target, which my sister and I, in our youth, worked toward as we filled the pages with brightly colored paper that garishly and over-decorated with stickers and cut-outs. The photographs were not our focus at the time. Today, my mother sits on the couch with me and shows me photos that she is sorting through, picking the ones to keep, the ones to send, and the ones to shred (my mother once told me to shred any photos I was throwing out in order to avoid becoming an art students project á la found art). I like looking through these family photos with my family. There is something that makes me feel connected when I learn the names and faces of my lineage, when I see photos of my parents before they were married, and when the power of genetics becomes so apparent as I see the baby photos of aunts and see the same face in children’s baby photos. But it has always been a collective activity.

Very rarely in my life have I sat down alone and looked through family photos. My mother or parents has always been my side, or sometimes even a slew of cousins, aunts, and uncles as we crowd on my grandparent’s couch to flip through scrapbooks. So, as I sat on my bed tonight, with a scrapbook and four boxes of photos to look through, I didn’t think I would it would feel different to look at them alone. I was wrong. Of course, I sat down with an objective, to find my own “Winter Garden Photograph,” which shifted my experience, but even with this searching mentality, I think that being alone while I looked was the most essential aspect of finding the photo. Instead of pointing out in features, deciphering the location or time, exclaiming at outfits and hairstyles aloud with others, as I looked at the photos I perceived and processed them internally. I held them only in my hands to see, not with arm extended or shifted away, to share with others. It was an intimate experience in which what I looked for in the photo was the essence that I understood of that person.

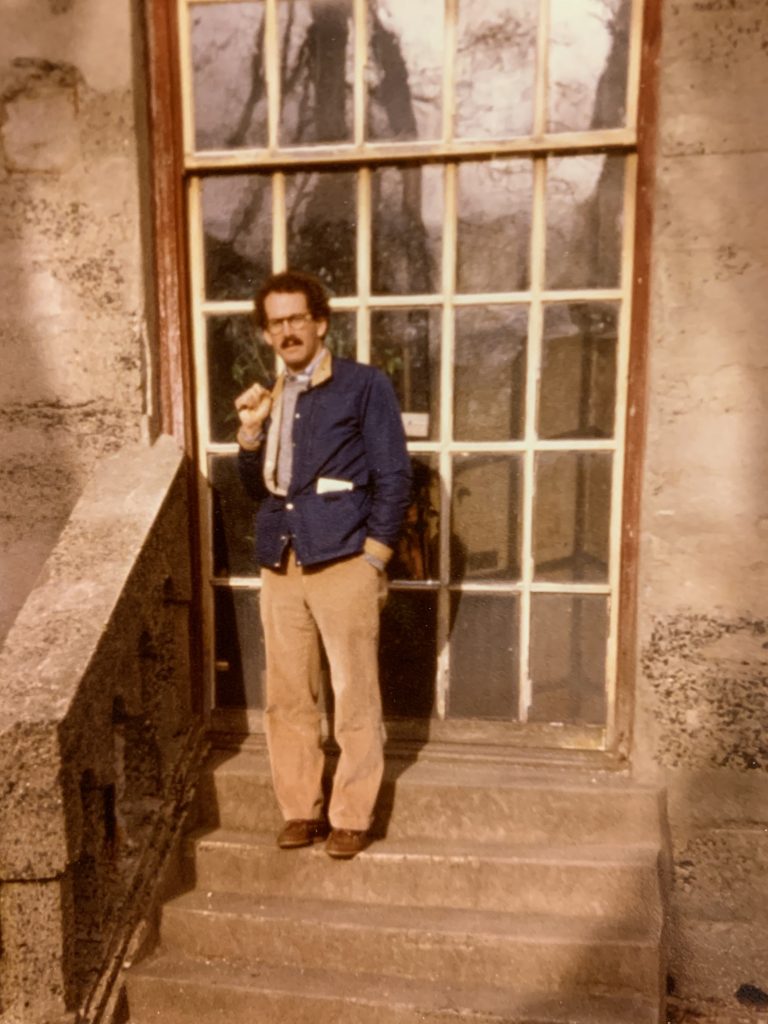

I didn’t come into the process knowing that I was going to look for a photo of my father. But as I continued to look at photos, I kept feeling myself looking at or for him in the image. Perhaps this is the result of stumbling across a truly iconic photo of my father, and from then wanting to just look for more, but I don’t think that is the only reason. There is something about my father that makes his true essence hard to capture. I have seen pieces here and there in other photos, but it’s hard to photo that I think really allows for me to feel the essence of his being. My “Winter Garden Photograph” did not immediately stand out to me. It is a photo of my father, standing in a place that I do not exactly know. I looked at it for a while, noticing my father’s posture, his clothing, his body language, but I kept moving. I realized as I had moved onto another box, that I was still thinking about that photo, one that was far less iconic from other photos, including one of my father standing in front of Half-Dome with his acid wash jeans and 80s ‘stache. And that didn’t exactly make sense to me, but thinking of Barthes, and what he writes about the photos that we still see or think about when our eyes are closed, made me realize that there was something in that photo, something that was drawing me in. What was pulling me back to the photo, I realized as I looked at it again, was that it contained in it an image of my father that embodied who he is. He is still, pensive, patient, serious, but playful. He is curious, intelligent, stubborn. He is himself, my father, but also not. He is the essence of himself in this photo.