The construction of time and our understanding of it is largely a linear one: stories are told with a beginning and end, lives are thought of as starting at birth and ending at death, most conceivable entities have an origin, and memory is understood much in the same way. The mechanisms through which time is measured even mirrors this linearity (calendars, for example, have a certain angular rigidity to them). Foregrounding our exploration of time with Michelle Wright’s text The Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, Wright urges for the use of epiphenomenal time “through which the past, present, and future are always interpreted.” (4) She further writes that this conception of time “denotes the current moment, a moment that is not directly borne out of another (i.e. causally created).” (4) In short, Wright calls for a less linear, more fluid, rhizomatic understanding of time and history, which she names “the now.”

Using this epiphenomenal time framework then, blackness, as Wright explores, is not really a what but more of a when and where. In texts such as Lose Your Mother by Saidiya Hartman and The Sovereignty of Quiet by Kevin Quashie, the examination of blackness, return, history, memory, and time all intersect to shift conventional constructions of blackness.

By examining blackness through the prism of when and where blackness is not stagnant. It becomes a moving target, something that is unfixed, ever-changing, ever-expansive. Using Wright, Hartman, and Quashie’s texts, as well as other contemporary works from visual artists, this section of the website, will provide us with the opportunity to reimagine blackness and its multitudes through non-traditional modes of time.

__________________________________________________________________________

Childish Gambino’s “This is America”

Childish Gambino, also known as Donald Glover, shocked the world with his music video “This Is America”. With over 10 million views in 24 hours, it sparked quite a bit of controversy. And while the song itself merits a book’s worth of conversation, I’m interested in looking at the music video through the lens of Michelle Wright’s theoretical framework of blackness.

Wright writes, “In the strict logic of cause and effect, white racism is the agent that sets the historical agenda for the Black progress narrative because it initiates the Atlantic slave trade (as opposed to slavery in Africa), Atlantic slavery, segregationist laws, racial violence, terrorist acts against Black communities, and exploitation- the list goes on, and in each moment, whiteness is the actor and Blackness the reactor.”[i]

Wright cautions against the use of “Middle Passage Epistemology”, which frames blackness in terms of white violence, and minimizes an infinite number of aspects, particularly agency, of blackness. Aspects of “This is America” exemplify the narratives of “Middle Passage Epistemology”.

Glover’s song and music video are certainly meant to express the severity of violence against black people in America. He specifically evokes: slavery, Jim Crow, gun violence, and police brutality. References to slavery are evokes subtly; for example, the pants that he is wearing are thought to be a Confederate soldier’s, which denotes war over slavery. There are also configurations that look like the ring shout, which was a popular means of resistance and survival by slave communities. In terms of Jim Crow, Glover evokes poses and facial expressions that denote Jim Crow Caricatures, which were historically made for the entertainment of white people. The scene of the shooting of the gospel choir, evokes a likeness to the Charleston Church Massacre, in which nine black churchgoers were killed in an act of racially motivated violence. Throughout the video there are police officers and police cars, which often appear while others are running. There is a particular scene where a police car has his lights on, and past the police car rides a white horse, a symbol of the apocalypse; perhaps, in this scene, Glover is highlighting the severity in which police brutality plagues the black community. Each of these scenes depict white racism as the agent of violence against the blackness. NPR illustrated this notion in a piece written soon after the video was released:

“It is representative of this history of violent white supremacy.”[ii]

Wright argues that “Middle Passage Epistemology” can be dangerous because whether, “explicitly stated or implicitly constructed through key moments of horizontal circulation- [it] cannot always incorporate all the dimensions of Blackness it seeks or sometimes even claims to represent.”[iii]

While Glover does extensively depict a narrative that Wright cautions against, he does depict a counternarrative, which enables broader depiction and understanding of blackness. For example, the music video does not use linear time, but is rather a snapshot of various events all taking place in the same space, a warehouse. This disruption of a linear narrative, allows Glover to portray what Wright calls the “now”. Wright defines the “now” as, “the only way to produce a definition of Blackness that is wholly inclusive and nonhierarchical is to understand Blackness as the intersection of constructs that locate the Black collective in history and in the specific moment in which Blackness is being imaged.” Glover is locating a specific moment in history, located in that warehouse, which he calls, “This Is America,” which intersects with aspects of black history, flawed as they may be in the eyes of Wright.

There was one scene that particularly struck me, as it stood out from the rest of the video. At about the climax of the song, and three fourths of the way through, Glover completely stops. His hands are in a position to shoot a gun and he lowers them in near silence. The scene of quiet is in categorical opposition to the rest of the video, which is chaotic and loud. Throughout the video, Glover’s character is uniquely humanized; he stares into the camera, bearing his soul, we see his emotions fully, and we, as viewers, become invested in his character. With Glover seemingly reflecting, eyes closed, in silence, lowering a gun, we see action formed from his own consciousness and volition, indicating interiority. Interiority and quiet are also a means of exercising agency and power, in a way that is not in opposition and resistance to whiteness.

In “This Is America” Glover cleverly toes the line in order to show racialized violence, but does so in a way that does not minimize Blackness to resistance, or a reaction to whiteness. Rather, Glover brings awareness to issues that disproportionately affect the black community, but does not reduce blackness to just these issues of violence.

[i] Michelle M Wright, Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology, (Minneapolis;London;: University of Minnesota Press 2015), 38.

[ii] Audie Cornish and Monika Evstatieva, “Donald Glover’s ‘This Is America’ Holds Ugly Truths To Be Self-Evident,” NPR, May 7, 2018.

[iii] Michelle M. Wright, Physics of Blackness.”, 60.

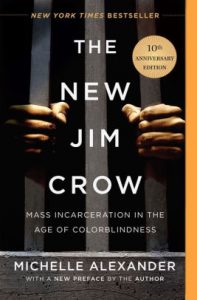

The New Jim Crow Proves Time is Not Linear

Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow is the first in-depth analysis of our country’s prison system and the mass incarceration of black men since the end of Reconstruction. Alexander exposes the ways in which the War on Drugs targeted black communities, and specifically, black men, as the most dangerous perpetrators of society. Alexander exposes the structural patterns of targeted criminalization of black men, resulting in the ever-increasing mass incarceration of black men and subsequent disastrous effect on black communities throughout the nation. She exposes funds granted to police departments throughout the country by the federal government, in which officers were directed almost exclusively toward policing black neighborhoods, where the federal government claimed was the epicenter of the “crack epidemic.” Coupled with the onslaught of policing of black men came the smear campaign against black women, who were depicted in the media as ‘welfare mothers’ who gave birth to ‘crack babies.’ Obviously there is much more to her research than I can fit in this post, but I highly recommend reading her book if you haven’t already.

Michelle Alexander’s study exposes our country’s prison system for what it is: slavery redesigned. Her book relates to the idea of time that we considered throughout our course this year as a result of Michelle Wright’s book, The Physics of Blackness. Our linear conceptualization of time allows us to believe that because time has passed since slavery and Jim Crow segregation, our society has made progress on the notion of racial equality. Our linear progress narrative allows us to blissfully ignore the inequities in quality of life for whites and non-whites; we ignore poverty rates, homelessness, incarceration rates, access to education and healthcare, and so much more. Our society is still divided by race, just as it always has been, because we are living in the now — aka, we are still experiencing slavery and Jim Crow segregation, but in a new, more subtle, form, as Michelle Alexander explains. If this theory sounds absurd, and you don’t believe me, just read The New Jim Crow.

This collage is a mix of photos of black artists, authors, activists, along with a poem by Evie Shockley, a photo of black Madonna, a photo of the Lorraine Motel, and a screenshot from a New York Times article about an online forum. I included the green spirals to represent oft-repeated history, the BaKongo cosmogram, and an emphasis towards thinking about time less linearly (as Wright pushes for). I wanted to create something artistic as a way to honor all those black musicians, theorists, and authors discussed in class this year.

BIO: DIASPORA VIDEO

Note: When quoting what people said in the video, I left the capitalization and punctuation as it appears in the subtitles in the video.

In a short 4-min film titled Bio: Diaspora, artist Emmanuel Afolabi weaves together seven vignettes, each of which is a personal reflection on what blackness is and means to them. Each of the vignettes shows a varying, individual perspective on blackness and how they each individually experience it in their day-to-day lives. Through its form and having such a diverse perspective of voice, Afolabi’s video shows the expansiveness and diversity in blackness.

https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/emmanuel-afolabi-bio-diaspora-film-290420

In the first vignette, Aysha Sow says, “Living here, [the United States] you are constantly reminded of how black you are. Or how black you are not. the question is always up in the air, do you identity as black? and in Europe, that’s not something that really comes up alot.”1 With this particular vignette, the role of place when thinking about identity comes into light. For Sow, when she is in the United States, her blackness is something that comes up often and that she is reminded me. However, when she is in Europe, her experience moving through spaces is different.

About Bio: Diaspora, Afolabi explains, “Bio is an identity series that explores the importance of contemporary black education through the revelatory stories of black people. I am inspired by life, the different people in it, the unique stories we share and the collective struggles.”2 In the film, each of the individuals depicted is presented the opportunity for reflection and to speak in an honest, thoughtful manner. Aflolabi acknowledges that there is a community to be had through struggle, but that individuals nonetheless have stories that are unique to their own lives.

Bio: Diaspora reminds me of Tressie McMillan Cottom short story “Black Is Over (Or, Special Black),” in which Cottom engages with ideas of being too black, not black enough, and what that means. She writes,

But, first, just what kind of black am I? It is actually a common question… Do I align myself with black people across the diaspora? With black people on the political left or the political right? With back people who have a nonblack parent?… The easy answer is that I am basic black. The harder answer is that it’s never as easy as it sounds.3

Cottom speaks to much of what those in Bio: Diaspora push back against, simply in describing their experiences. Instead of viewing each person as an individual, Cottom is discussing the oft-asked question she receives about the specific type of black she is, as if blackness is something with clear categorization. The rest of the essay depicts Cottom engaging with this question of what kind of black she is and ultimately comes to the conclusion that blackness must be decided and experiences individually.

Additionally, Bio: Diaspora touches on so many of the themes brought up in this class.

The decision of choice arises: in the first vignette, Sow says, “whereas over here [the United States] you could be a visibly black person and black will still wonder, do you identify as a black person which in some cases here, there are people who don’t identity as black who is visibly black.” 4

The idea of blackness as resistance and reaction is brought up: in the third vignette, Lili Lopez says, “my friend said it right actually. if feels like here being black is a reaction to something because it has a lot of negativity but to me, it has ever been negative. And in anything that I do I am black out of me just being and it’s not a reaction to a race issue or a race conversation…”5

History and the past comes up when Denzel Bryan reflects, “the foundation of the world when it comes to art, culture, music, even the land that we walk on day to day, was built on by my ancestors, so I think that’s something that I always have to keep in mind…”6

And the idea of being a foreigner and what that looks like is reflected upon by Olive Uche when she says about her parents, “Imagine being African, or just being a foreigner and you are coming probably during the 70s or 80s, not knowing anything, not knowing the language as much, and you have to compete on a larger scale…”7

Ultimately, Bio: Diaspora engages with what it means to be black and through its format of vignettes resists the idea of any type of incredibly linear history of blackness.

1 Emmanuel Afolabi, “BIO: Diaspora, ” Published February 23, 2020, Video, https://vimeo.com/393255623.

2 It’s Nice That. “Emmanuel Afolabi’s new film, Bio: Diaspora, explores the importance of contemporary black education.” Published April 29, 2020. Written by Ayla Angelos. https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/emmanuel-afolabi-bio-diaspora-film-290420.

3 Tressie McMillan Cottom, “Black Is Over (Or, Special Black),” In Thick: And Other Essays, 127-152, New York:

The New Press, 2019, 132.

4 Emmanuel Afolabi, “BIO: Diaspora, ” Published February 23, 2020, Video, https://vimeo.com/393255623.

5 Ibid., “BIO: Disapora, https://vimeo.com/393255623.

6 Ibid., “BIO: Disapora, https://vimeo.com/393255623.

7 Ibid., “BIO: Disapora, https://vimeo.com/393255623.

Joyner Lucas’ Music Video, I’m Not Racist

The video opens to a young white man with a beard, wearing a MAGA hat and staring intensely into the camera, as if he is addressing the viewer directly. He claims “with all due respect, I don’t have pity for you black n-words that’s the way I feel.” The screen only shows the white man until 28 seconds in, when the perspective shifts to show there is a young black man sitting across from him. This is unexpected – this man spewing ignorance and racial epithets has been speaking directly to a black man the whole time. The rest of the music video shows the white man completing his unfiltered rant about his feelings about black people, and then the black man’s response to him. The monologues of both characters relates to Michelle Wright’s conceptualization of time, and more specifically, of the now.

Firstly, the racial stereotypes that the white man lists remind me of the now because they are simply centuries-old racism that has taken a different form, and hides behind ‘free speech.’ The white man depicts black people in general but specifically black men as lazy, bad fathers, impoverished, and ‘ghetto.’ Every stanza, he attempts to mask his racism by saying “I’m not racist,” the phrase that is repeated throughout the song. The repetition of this phrase reflects its frequency of use in our society as a justification for saying or doing racist things. In using it in this song, Joyner Lucas exposes this phrase for what it really is: a crutch white people use to protect themselves from the truth that they are racist, to hide behind a lie, to allow their contribution to the maintenance of white supremacy to remain invisible to them. This phrase and the use thereof reminds me of the ways in which white slave owners would justify slavery to themselves by saying black people were less than human, that they treated their slaves like their own children, that they give them purpose, etc. The repetition of this phrase is therefore a metaphor for the cyclical and repetitive nature of history, similar to Michelle Wright’s conceptualization, that shows us how little progress our society has actually made since slavery.

In his monologue, the young black man responds to almost every single one of the ‘points’ that the white man made by pointing out the flawed logic in his thinking and sharing his reality with the white man. As an explanation for why the white man (or, rather, white people in general) don’t understand his experience, he says “It’s like we livin’ in the same buildin’ but split into two floors.” With this line, he recalls segregation and shows how we are still living in that ‘now’ — albeit races may not be legally segregated, Lucas asserts that our society is still split along racial lines. This line illuminates Wright’s explanation of the linear progress narrative — we think that because time has passed since segregation ended, progress has been made. The linear progress narrative allows us to live a life where we don’t have to confront how little progress we have actually made, whereas the ‘now’ forces us to confront the ways in which racism has simply taken on new forms that we ignore.

This video and the lyrics are ridden with significance and relation to Michelle Wright’s ideas as well as other themes we have discussed in our course. I picked out a few moments that stuck out to me, but almost every single line in this song could be analyzed for its significance. This video is worth a watch, or five, or twenty.