What is blood? Biologically, blood is a liquid in the human body, which serves to keep the body alive. In this sense, blood is physical, and tangible, as you can palpably see, and at times even feel it; but blood also functions intangibly. The main character of the literary novel, Iola Leroy, speaks about the conception of African blood, or more generally ancestral blood: “The best blood in my veins is African blood, and I am not ashamed of it.” (200) African blood, an intangible notion of identity, is how Iola Leroy conceptualizes, and notably claims, her blackness. Yet others reject this notion. Mary Ellen, a Ghanaian resident featured in Saidiya Hartman’s, “Lose Your Mother,” rejects the confluence of African ancestry with blackness: “I’ve been here too long to call myself anything except a black American. This is what feels true.” (29) Mary Ellen rejects the idea of African blood as defining her blackness, as by living in Ghana she found that there “was no longer a future in being an African American, only the burden of history and disappointment”: Mary Ellen chooses to define her blackness by the prospect of the future, rather than history, which she felt she could not personally identify with (29).

Blackness can also be conceptualized through blood ties, particularly through the mother. Historically, a person’s slave status was defined by the mother, meaning that those children were defined as black. Iola Leroy serves to exemplify this notion, as characters in the novel that are white passing all chose to claim their blackness, and not insignificantly, all of these characters’ mothers are black.

Religion and spirituality can serve as a lens to understand and conceptualize blackness. In particular, Christianity, which includes services and beliefs devoted to the body and blood of Christ, has shaped and characterized blackness across space and time. In a manner, Christianity, particularly in times of turmoil and trauma, has served as a lifeblood of black communities. However, although Christianity may be a central aspect of blackness across certain spaces and times, certainly not all black people identify as Christian.

In both juxtaposition and complement to blood there is choice. “Iola Leroy” exhibits this tension: “He belongs to that negro race both by blood and choice. His father’s mother made overtures to receive him as her grandson and heir, but he has nobly refused to forsake his father’s people and has cast his lot with them.” The “He” in this quotation is a white-passing doctor who chooses to claim his blackness, regardless of attempts by his white family to “shield” him from his blackness.

Within ancestry and history there is a choice to reject or accept it. Within family, or blood ties there is a choice regarding belonging. Within the Christian community, or blood and body of Christ, there is choice. Within and in contrast to blood there is choice.

________________________________________________________

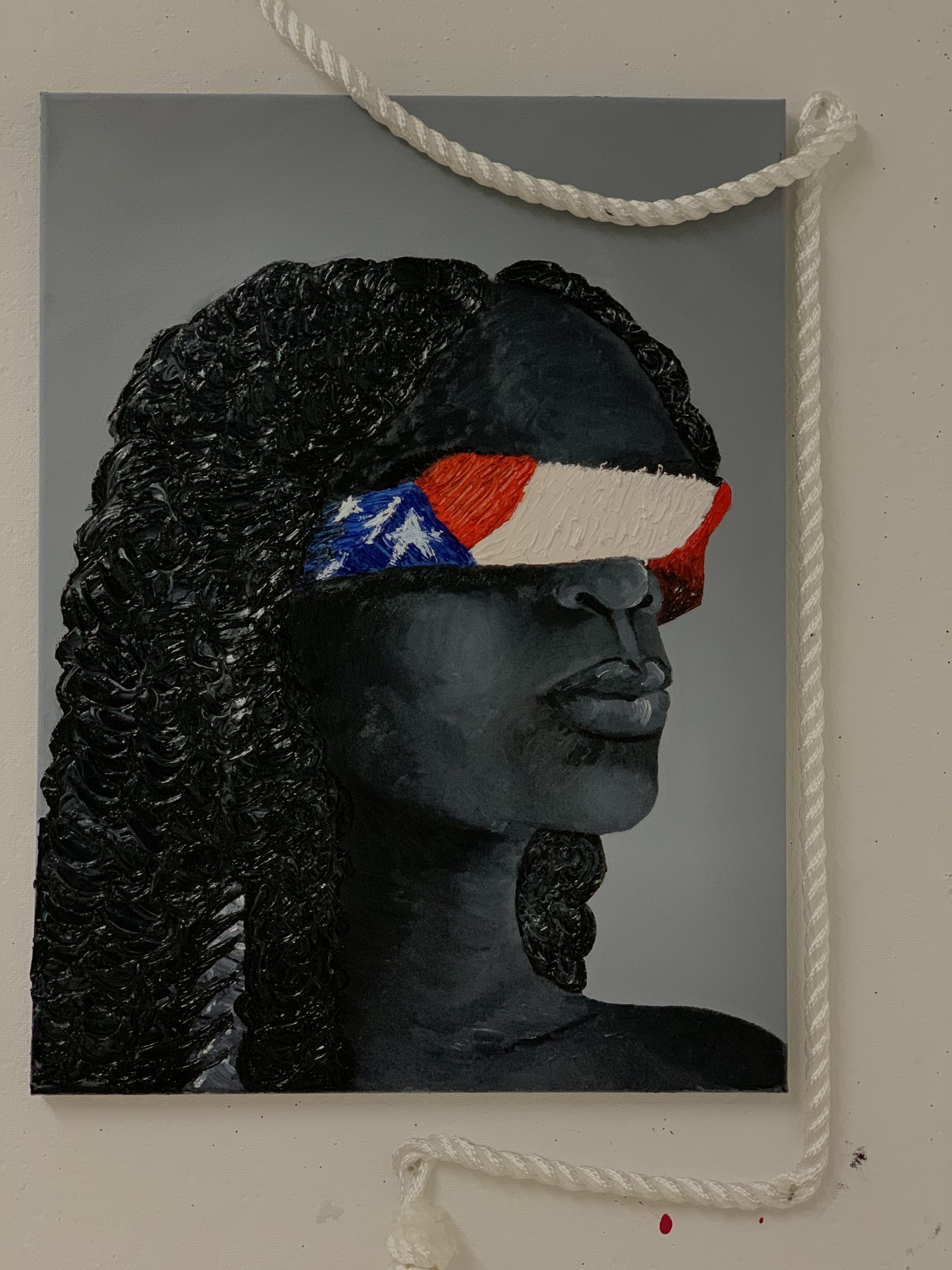

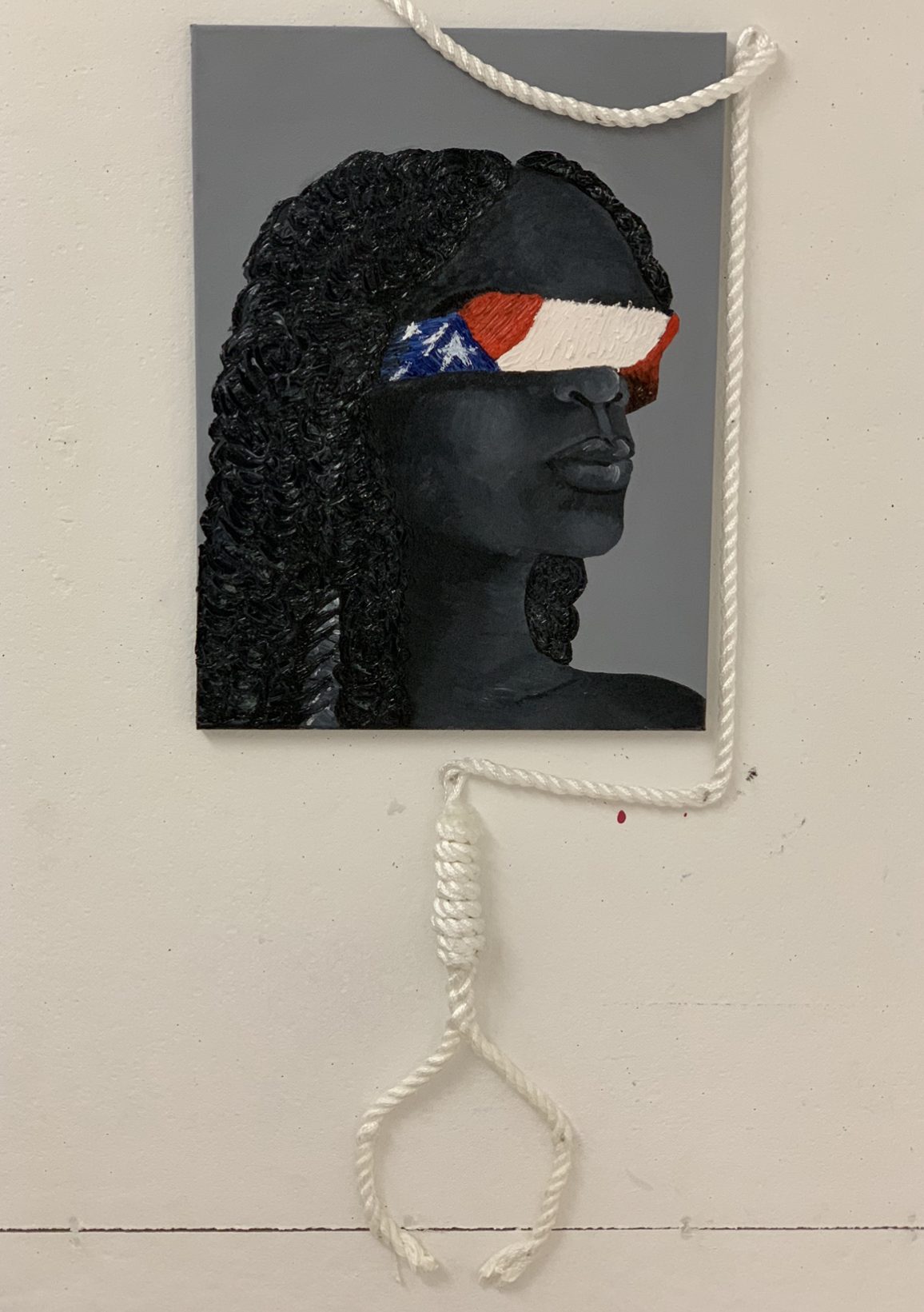

Destiny Kearney, Repression and Resistance, Oil Canvas Oil, 2020

This painting highlights both the feelings of repression and resistance that I as an AfroNative woman in the context of the American 21st century. I created this self-portrait by pushing thick layers of oil paint on to the canvas with a brush and a palette knife, hence physically engaging with the painting with a force that echoes the theme of “resistance,”. In creating this piece I wanted to touch on parts of my identity that have shaped who I am and being an African American and Native American woman, I’ve struggled a lot with my place and finding a “home” in the country I was born. The history of my ancestors is one of violence and genocide, and this history lives in me, even in a contemporary context.

This painting confronts the violent past that is symbolized in the American flag, which is printed on the blindfold covering over my eyes. It represents bondage that is very much still present today for my people. The noose that hangs alongside the painting, only to fall at the bottom and reveal itself as broken, is the symbol for repression. As I grow older and become more fond of my history I acknowledge the violent actions, but they no longer fuel or define who I am. My ancestors existed before these acts of violence occurred. It symbolizes a newfound motivation to push forward and take pride in who I am and where I come from.

This painting and its process have caused me to think a lot about what blood means to me, but also place. I am a native American from my great grandmother who is 100% Wampanoag and based on my physical appearance people wouldn’t assume that I had native blood in me. It is something that I could’ve chosen to omit and hide from those around me because I could pass as if I was not, but learning about my history and taking pride in that has pushed me further in acknowledging who I am.

The Conceptualization of African Blood

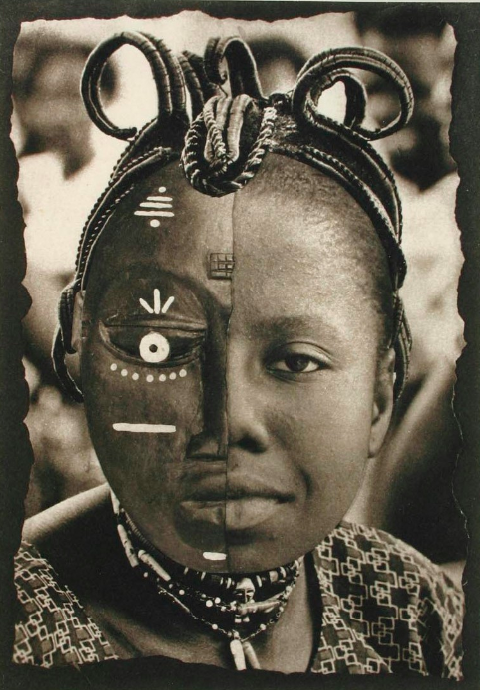

Gene Young, Conjure Girl, 1989.

On the integrality of conjure to blackness, Chireau writes, “it is certain that during slavery, and even beyond, Conjurers were highly visible figures on the cultural landscape in black America.”[i] Conjure was a powerful tool of both resistance and agency in the enslaved community.[ii] Chireau writes, “Conjure beliefs enabled some black bond persons to chip away at the foundations of slaveholders’ authority, sometimes through small, disabling acts.”[iii] Conjure practices, like rootwork, certainly provided black bond persons the means to resist the systematic oppression of slavery. Conjure, and other various practices involving African cosmological symbols and beliefs, also enabled black bond persons to achieve agency, apart from systems of oppression, by providing systems of empowerment, completely outside, and free of slavery. Chireau illustrates this notion, “Attaining power—over one’s destiny, over one’s circumstances, over one’s environment—was a particular concern for African Americans… It may be argued that conjuring traditions allowed some blacks to achieve a conceptual measure of control and power over their circumstances.”[iv] Conjure was a means of both agency and resistance; notably, these practices were strongly associated with Africans, or more particularly, African blood.

“Conjurers were “full-blooded Africans,” a designation that affirmed the geographical and spiritual roots of conjuring practices.”[v]

Conjurers were a “highly visible figures” of black America, and were linked with African blood. The association of African blood and blackness is not uncommon. Iola Leroy, novel by Lorraine Hansberry, also addresses this association: “The best blood in my veins is African blood, and I am not ashamed of it.”[vi] You can also find references to the notion of African blood in pop culture. For example, Kendrick Lamar, in his song “DNA”, poeticizes:

I got, I got, I got, I got

Loyalty, got royalty

Inside my DNA[vii]

Lamar could perhaps be referencing African royalty, which is in his heredic makeup, or DNA, which is found in blood. Blood is interesting because it complicates linear time, in that it encompasses past, present, and future. Conjurers as “full-blooded Africans,” denotes a link to African roots of spirituality conceptualized in present Conjurers. Kendrick Lamar evokes ancestral royalty of African Kings and Queens, which still course through his veins via DNA. In this sense of time, blood has sustaining power in the conception of identity. It is unsurprising then, that across certain spaces and times, blackness has been conceptualized in terms of African ancestry, or more specifically African blood.

[i] Yvonne Patricia Chireau, Black Magic: Religion and the African American Conjuring Tradition, (Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press, 2003) 13.

[ii] Sharon K. Moses, Enslaved African Conjure and Ritual Deposits on the Hume Plantation, South Carolina, Vol. 39. (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications, 2018).

[iii] Chireau, Black Magic, 18.

[iv] Chireau, Black Magic, 24.

[v] Chireau, Black Magic, 33.

[vi] Frances Ellen Watkins Harper. Iola Leroy, Or, Shadows Uplifted. Vol. 739. Boston: Beacon Press (1987), 200.

[vii] Kendrick Lamar, “DNA,” Damn, (Warner Chappell Music, 2017). https://www.lyricfind.com/.

______________________________________

ODE TO THE BLACK PEOPLE AT THE WHOLE FOODS BY THE HOUSE I GREW UP IN

Where were you when I was 14?

I really needed to see your glowing skin and beautiful bodies.

(I mean, so that I could see my own)

In our class this semester, we troubled the idea that blood is intertwined with the concepts of family, heritage, and ownership. Within the broader thematic framework of blackness as a fluid concept, our professor constantly challenged us to destabilize hegemonic ideas about the body and identity. In our class, the body re-emerged within different contexts. We discussed the racialization of Foucault’s ideas concerning bodily surveillance, the legacy of bodily exploitation and experimentation within black communities, and the body as a site of both surrender and liberation. Theoretically, we examined bodies of work that represent aspects of individuals’ perspectives and experiences within the African diaspora, ranging from paintings, to music videos, to literature, and to movies. There is so much beauty in all the creative and expressive mechanisms through which black people reveal their intimate lives, the truth at the core of who they are. In this section, I reflect on the work of artist Mikael Owunna, a photographer who used the project Infinite Essence to subvert the prevalent popular media practice of portraying black bodies as violent, associated with death and danger. His work links the black body to the cosmological domain, asserting a divine connection to magical and celestial spaces.

I link Owunna’s work to a short poem by Rin Johnson, a conceptual artist based in Brooklyn, because his phrase “I really needed to see your glowing skin and beautiful bodies” speaks so eloquently to the power of beauty within representation. He clarifies the statement by continuing that the reason he needed to see those beautiful bodies is so that he, too, could recognize the inherent beauty and worth within himself. What do we have to lose with the skewed representation of black bodies? What do we stand to gain when we collectively recognize and celebrate the beauty of black bodies?

Owunna asks his audience, “What if the only images you saw of people who looked like you were dead and dying bodies? How would that affect the way you move through the world?” His question probes beyond surface-level arguments for representation within film or popular media disseminated throughout popular culture. He cuts to how black bodies are shown, displayed, and commodified within news coverage or popular movies – Tarantino’s films in particular come to mind – and suggests the potential for an embodied exhaustion. The high rates of hypertension within African Americans further implicates the role of repeated and enduring stress within the body. If that amount of damage occurs within the veins and blood of individuals, what destruction does misrepresentation cause to a person’s psyche?

The mind and body are inextricably connected, contrary to the common Western assumption that dichotomies divide our lives and bodies. Owunna draws on the Igbo spiritual concept of “chi” in every person, the soul of each individual. The chi is infinite and so are we. The photographs Owunna produce illustrate the inherent chi that exists in black bodies as spiritual beings, transcending the mortal plane and disrupting linear structures of time or place. As the audience, we are not just passively looking at these photographs, but actively engaging with them cosmologically and spiritually.

At the time of this post, May 2018, the footage of Ahmaud Armery is being widely disseminated across social media platforms like Twitter. The circulating footage embodies Snorton’s analysis that “the recurrent practice of enumerating the dead in mass and social media seems to conform to the logics of accumulation that structure racial capitalism, in which the quantified abstraction of black and trans deaths reveals the calculated value of black and trans lives through states’ grammars of deficit and debt,” marking black bodies as commodities (Snorton, 12). The recording of his murder drew attention to the Atlanta case, but it is imperative to problematize how black death is represented and distributed in the news cycle, and how videos and images of death can perpetuate trauma. Without intentional action, what does consumption of those images promote? How do non-black people make a conscious decision to publicly celebrate and display the lives and beauty of black people?

Jay-Z’s “Oceans”

Elephant tusk on the bow of a sailing lady, docked on the Ivory Coast

Mercedes in a row winding down the road

I hope my black skin don’t dirt this white tuxedo before the Basquiat show

And if so, well fuck it, fuck it

Because this water drown my family, this water mixed my blood

This water tells my story, this water knows it all

Go ahead and spill some champagne in the water

Go ahead and watch the sun blaze on the waves of the ocean[i]

Jay-Z plays on conventional linear understandings of time in his song “Oceans”. The first line of the song and chorus, “Elephant tusk on the bow of a sailing lady, docked on the Ivory Coast,” evokes images of the past, which starts on the Coast of Africa. This line addresses two parts of the slave trade: the Middle Passage and the First Passage. In the 19th century, during colonization, the Ivory Trade intensified within Central Africa. Like black African bond persons, the ivory was taken from the interior of Africa and brought to the coast. The First Passage is not nearly as widely acknowledged as a part of slavery, in comparison to the Middle Passage. The “sailing lady,” though currently “docked on the Ivory Coast,” implies movement across the water of the Atlantic Ocean, also known as the Middle Passage. After this powerful line, Jay-Z transitions back to the present moment with the line, “Mercedes in a row winding down the road.” In the present time, the movement being described is not that of past black bond persons but of contemporary wealthy people that are also traveling. This conflation of past and present will continue with Jay-Z’s conception of water.

With the line, “This water drown my family,” Jay-Z is evoking the trauma and tragedy of the Middle Passage. Many black bond persons did not complete the Middle Passage journey due to horrendous and dehumanizing conditions on slave ships. In the same breath, Jay-Z poeticizes, “This water mixed my blood.” This line is so incredibly powerful because it conflates the past and present. The same water that both carried, killed, and changed the realities of black bond persons, is the same water that courses through the veins of Jay-Z. Through the conflation of past and present Jay-Z is acknowledging the importance of his ancestors, and draws parallels between them.

The line “Go ahead and spill some champagne in the water,” indicates that water is not stagnant but is ever fluid and evolving. Champagne is the liquid form of celebration. The fact that Jay-Z mentions champagne connotes that he is repositioning the same water, recalled from the Middle Passage, in terms of the current social position of a wealthy and successful black man. The water that courses through Jay-Z is multidimensional, evoking historic pasts which have shaped him, while also representing a celebration of his wealth and luxury.

Through the water Jay-Z is also able to reclaim history. By flippantly “spilling” champagne in the water, he is pointing to the fact that the past is only so important, and perhaps it’s what you make of the past, like pouring champagne on it, is the most important part. The song later expands upon this idea in the line, “I’m anti-Santa Maria, only Christopher we acknowledge is Wallace.” Jay-Z is no doubt condemning the mal-treatment of Native Americans, who suffered at the hands of Christopher Columbus, but he is also condemning the treatment of history. Christopher Columbus Day is still celebrated as a national holiday in America, despite his atrocious acts. By “pouring champagne” in the water, which “knows his story” and formed his blood, Jay-Z is claiming this history, and repositioning it on his own terms.

This song reminds me of the saying, “blood is thicker than water,” but in this case the water has actually formed the blood. Jay-Z is both evoking and reclaiming the notion and history of Middle Passage in order to show the importance of the past as it informs the present.

[i] Jay-Z, “Oceans,” Magna Carta… Holy Grail, (Pharrel Williams, 2013). https://genius.com/albums/Jay-z/Magna-carta-holy-grail.

Little Fires Everywhere

Originally a novel published by Celeste Ng, Little Fires Everywhere was released as a TV series on Hulu this spring. Starring Kerry Washington and Reese Witherspoon as the leads, the 10-episode series follows Mia Warren (played by Washington) and her daughter Pearl as they move to Shaker Heights, a small, affluent, white town in Ohio. Soon, the Warrens’ lives become intertwined with the Richardson’s, lead by matriarch Elena (played by Witherspoon). As the two families become increasingly entangled, tensions arise and the series ends with the Warrens leaving Shaker Heights.

The show deals with topics such as adoption, abortion, wealth inequity, queerness, privilege, race, and above all, choice. Though a majority of the show is set in 1997, multiple episodes include flashbacks to both Mia and Elena’s youths, allowing the audience to better understand their characters. Mia, unable to pay tuition for her second year of college, becomes a surrogate and ultimately ends up keeping the baby, leading to her becoming estranged from the family and having to constantly move. For Elena, we see her struggling with her role as a journalist and mother, trying to juggle what she wants with what society expects of her.

In one particularly striking moment of the series, during a discussion about motherhood, Elena tells Mia, “A good mother makes good choices,” to which Mia responds, “You didn’t make good choices, you had good choices! Options that being rich and white and entitled gave you.” Elena retorts, “Again, that’s the difference between you and me. I would never make this about race.”1 Elena’s comment about race is particularly poignant as the idea of color blindness was a popular ideology in the 90s.2

In this episode, theme of choice becomes abundantly apparent. Because of white privilege and having grown up with money, Elena has access to resources and opportunities that Mia does not have (or that she would have to work much harder at to get). Mia’s identity as a black, single, working-class woman influenced her decisions when running away from home, deciding to keep her baby, and more. Particularly as Mia and Elena are occupying the same spaces throughout the TV series, the difference in how they move through and engage with these spaces is even more apparent.

In an article published in The Atlantic, Shirley Li writes, “The concept of caging others and being caged by others—based on one’s background, values, and lifestyle—is a pivotal theme in Ng’s novel. Throughout the first half of the season, defining the Warrens as black complicates that theme.”3 With this quote, Li is referring to the change the TV show’s producers took in casting the Warrens as black (in Ng’s novel, their race is never mentioned). Caging and choice are related as caging someone, in whatever form that is, automatically takes away their agency and diminishes the possibility for fruitful, rich relationships and futures.

Ultimately, the aforementioned scene in Little Fires Everywhere highlights the degree to which having choice can be related to privilege.

1 Little Fires Everywhere, “The Spider Web,” Directed by Lynn Shelton, Written by Attica Locke, Hulu, March 25, 2020, https://www.hulu.com/watch/9131b77b-95cb-4173-baca-6f361fe035f2, 30:40.

2 Shirley Li, “When a TV Adaptation Does What the Book Could Not,” The Atlantic, March 31, 2020, https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/03/little-fires-everywhere-hulu-series-pivotal-change

3 Li, “When a TV Adaptation Does,” https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/03/little-fires-everywhere-hulu-series-pivotal-changefrom-novel/609151/.

Praising Ancestry

Edwaujonte’s writing is “…rooted in ancestral ritual” (Edwaujonte 2019, 7). Ofrenda: para las ancestras is a book of poems written by Edwaujonte as an offering to his ancestors and spiritual beings. Blood represents familial ties, and in this context, these familial ties are expressed through writing. His writing functions as roots that connect him to his ancestors. He praises his Abuelas’ cooking in “Ofrenda para mis Abuelas.” Next to the name of a specific dish is “Grandma Claire” or “Mama Anna.”

“Blessed be the rice and beans and peas and jolof/jambalaya jolofalaya” (13).

His grandmothers’ dishes are theirs, but they became a part of him when he accepted their food traditions in his life.

Edwaujonte includes a written eulogy to his grandfather. This piece is not written in stanzas but still holds praise to his grandfather “There is no school that lays out a blueprint to be a grandfather. If there were, your life would be its canon” (49). He holds his grandfather’s advice and inspiration just as valuable as the work of an academic in their field. His grandfather’s experiences are traditions that are just as worthy as academic books.

“we gather beneath this weeping willow of a house witnessing the stump of a family tree retracing the phantom trunk that reaches back to a Sahel we never knew…” (51)

The use of “we” in his poem “Jones.” can allude to Edwaujonte’s experience with his ancestry. His family tree is only a stump, but there is a “phantom trunk” that connects his ancestors to him. This “phantom trunk” is a result of the lack of visibility of records of enslaved black people, that do exist.