Black pride embodies the interior and exterior of blackness as it shifts and changes from body to body and culture to culture. Black pride is a consistent theme we have encountered either explicitly or implicitly each week throughout the course. Although I could speak about its existence in every reading and documentary we’ve watched, it is more effective to focus on the commonality of them all – dispelling the monolith of Blackness. To understand the way Black pride functions, one must understand that Blackness is multidimensional and exists in different social, political, and economic spheres. These all represent the outer spheres of how to view black pride, but Kevin Quashie reminds us in The Sovereignty of Quiet, to look past theorizing Blackness through the lens of resistance that is public, loud, and dramatic. He encourages readers to analyze the Black experience through the interior, or what he calls quiet. Quiet highlights “one’s inner life—one’s desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears.” (6). This speaks about the “full range of one’s inner life” that is absent from race/racism but focuses on the essence of their being. To understand Black pride, one must see that Blackness isn’t just an observable quality based on physical traits, but needs dissecting of the mind and the spirit; the interior.

In Iola Leroy; Or, Shadows Uplifted, the main character, Iola discovers her blackness later on in life after living as a free white woman during slavery. Her parents chose to let her pass as white as a means to protect her, but when her father dies, and her envious uncle reveals the truth about her family, she is confronted with her identity and forced to deal with it. Iola chooses to embrace her Black identity by advocating for racial empowerment and civil rights. Another example of Black pride can be seen in the Nina Simone documentary, The Amazing Nina Simone, as she reveals herself to us as unapologetically Black. Black with pride, and not caring about what anyone else had to say about it. Nina’s Black pride can be seen on the outside as she embraced Afro-centric dress and natural hair, along with her interior through her music. Her song “Young Gifted and Black,” (inspired by Lorraine Hansberry) along with others, opened the doors for others to take pride in their Blackness, and Nina was vulnerable enough to share this with the world. Black Pride also exists across different times and socioeconomic backgrounds. In Imani Perry’s biography Looking for Lorraine she speaks about the pride Hansberry had as a highly educated Black lesbian woman during the 1950s. While Geneva Smitherman brings to light the pride that exists historically in Black Vernacular English. Black Pride isn’t strictly physical but can exist within the interior, in education, art, and culture. As you conceptualize this theme, I encourage you to ask yourself these questions: Can Black Pride only exist amongst Black Bodies? When and Where is Black Pride? Can Black Pride be “Quiet?”

____________________________________________________

A Seat at “Her” Table: How Solange Expresses Black Pride Through Music and Commentary

A Seat at the Table, is Solange’s third album that was released in 2016. Within the lyrics, instruments, and beats Solange creates an album that highlights all aspects of her Blackness. As she touches on the physical, she also brings the listener into her interior. Rolling Stone in, a review of her album says A Seat at the Table, is a record about black survival in 2016; a combination of straight talk and refracted R&B for what she calls her “project on identity, empowerment, independence, grief, and healing.” As we think about Black Pride, it is important to acknowledge the different spheres it can navigate. Through a mix of music and commentary, Solange provides the listener with a look into the different aspects of her life.

Don’t Touch My Hair highlights the physicality of her hair, but describes its intimate and personal connection to who she is. Mad where she expresses her own frustrations and anger and touches on loneliness. F.U.B.U where she calls out to the Black community speaking about unity and the repetition of the word “us” to reiterate that feeling of togetherness. It speaks on the struggles Black people feel but can connect over. Weary where she confronts this idea of belonging within the world. In this song she touches on finding her body and having the realization that “a king is only a man with flesh and bones, he bleeds just like you do” which highlights this humanness we all share. Hierarchy is a manmade concept and this realization allows her to find that belonging.

As apple music quotes “a confessional autobiography and meditation on being black in America, this album finds Solange searching for answers within a set of achingly lovely funk tunes.” This album takes the listeners on a journey of searching as Solange searches through herself, the listener gains insight on what her understanding of Blackness is in all aspects of her life. She takes pride in the process as she documents it through music and commentary and provides us with “A Seat at the table” with her as we find these answers.

_____________________________________________________

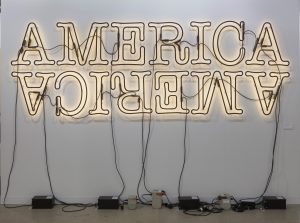

Photo Credit: The Broad

When I first encountered Ligon’s “Double America 2” I was struck by how much the image reminded me of Jordan Peele’s 2019 horror film, “Us.” In that movie, the characters discover their doppelgangers, hidden for years literally right beneath the humans but always invisibly connected. Much like that movie, “Double America 2” speaks to how duality fundamentally shapes the black experience. DuBois’ concept of double consciousness suggests that black people are always aware not just of how they see themselves, but of how they see one another. Yet this idea can be pushed even further to include Quashie’s concepts of the tension between interiority and one’s public persona.

Quashie argues that black people are too often confined to a monolithic identity that denies individuals the ability to explore their private, vulnerable selves outside of the public (white) gaze. Interestingly, Ligon himself explores this conceptual theme through his work as a leader of the post-blackness movement. Post-blackness is an artistic and philosophical argument for the reconciliation of blackness as a construct with the lived experience of African Americans, liberating artists to explore racial themes without their work being interpreted as a representation of all black people. Embracing duality while theorizing blackness grants art the permission to be simultaneously exterior and interior, public and private, individual yet connected.

Jordan Peele’s film “Us” is a horror film that confronts American audiences with the unseen violence that lurks underneath America’s surface. In the movie, there are people (The Tethered) who live underground, and there are people who live on Earth, unknowingly connected to The Tethered. When I look at “Double America 2,” I immediately connected the intricate lines between both Americas and the invisible connection between the Tethered and the un-Tethered (in the film, represented by the scissors as recurring symbol). Similarly,“Double America 2” reminds us that these two Americas operate alongside one another, inextricably connected and defined through one another.

There are different lived experiences for people of color, and black people specifically, than the worlds white people enjoy access to. Racism can be ignored by white people while people of color confront racism in nearly every aspect of contemporary social life – the legacy of redlining, disproportionate access to resources such as education, healthy food, and healthcare, continued discrimination, to only name a select few. In fact, one could argue that black Americans experience a completely different America than white people. “Us” takes the idea of a dual lived experience and pushes the audience to grapple with the question of what can and would happen when the ugliness pushed beneath the surface erupts, in an explosion of rage and violence. More importantly, what culpability do the un-Tethered have and what do they owe The Tethered? How do we position ourselves to better see and understand the worlds and experiences that we ourselves do not live through?

Beyonce Runs the World

In 2016, Beyonce performed her song “Formation” at the Superbowl. Beyonce is a popular symbol of “Black Excellence,” and she therefore can be seen as a prime example in our category ‘black pride’ due to her reputation alone. She is both an emblem of black pride, as well as a proponent thereof. Perhaps her emblematization is a result of her advocacy for black pride. In this post, however, I will analyze this performance for how it defines, expresses, and encourages black pride. Beyonce’s first line, “okay ladies now let’s get in Formation” is coupled with a move in which Beyonce and her backup dancers, who all appear to be black women, form rows with beyonce as the head. This imagery implies support, that not only does Beyonce rely on her backup dancers (or, for metaphorical purposes, black women in general), but they contribute significantly to her identity and fame. From this, we can assert from Beyonce’s reputation, that black women are black excellence in that they make up the basis for Beyonce’s platform, and are her community.

The lyrics themselves are even an example of black pride in that they praise and celebrate black culture. Here is an excerpt to illustrate this claim:

My daddy Alabama, momma Louisiana

You mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bamma

I like my baby hair, with baby hair and afros

I like my negro nose with Jackson Five nostrils

Earned all this money but they never take the country out me

I got a hot sauce in my bag, swag

In this stanza, Beyonce tauts aspects of black culture that she takes pride in: afros, a ‘negro nose’ with Jackson Five nostrils, money, hot sauce, and her connection to the south/”country.” Although these may not be qualities that every single black person can personally relate to, they are qualities that are definitively stereotypically connected to blackness and black identity. Beyonce reclaims these aspects of identity that have been associated with negative stereotypes by white people, and praises them as a source of pride and black excellence. This reclamation is especially significant due to the platform of the performance, on the field at the 2016 Superbowl during halftime.

The 2016 Superbowl had 111.6 million viewers, from all different races, ethnicities, and nationalities. That means that Beyonce’s performance and message reached a huge audience. Her performance, posted on youtube, has 1 million views and her music video for the song has 205 million views. This speaks not only to the popularity of black pride, but also the acceptance thereof. Beyonce’s work in general encourages black people to embrace their ‘black excellence’ by taking pride in their heritage, their identities, their communities, and one another. She is both a role model and a leader, setting an example to the world about what it means to be proud to be black.

Analysis of “Afro-Latina”

A Poem by Elizabeth Acevedo

“Afro-Latina, Camina conmigo. Salsa swagger anywhere she go, como ‘¡la negra tiene tumbao! ¡Azúcar!’ Dance to the rhythm. Beat the drums of my skin. Afrodescendant, the rhythms within.” I got chills the first time I heard Elizabeth Acevedo’s poem “Afro-Latina”. Acevedo’s words are powerful, vivid, and speak from the perspective of one Black intersectional identity that is overlooked, Afro-Latinx. In the poem, Acevedo discusses her personal evolution with coming to appreciate and be proud of her racial identity.

Initially, she is embarrassed by her immigrant family, because they are nowhere near the margins of whiteness according to her peers. However, learning the history of Afro-Latinx identity shifted what she thinks about herself and her family; It is the impetus to her finally loving her Afro-Latinx identity. This is shown when Acevedo exclaims, “They’re in the bending and blending of backbones. We are deformed and reformed beings…We are the unforeseen children.” Acevedo is proud of her ancestors, because of the hard work and oppression her ancestors endured and rose from. She views them as resilient due to Afro-Latinos and Blacks ability to continue progressing in the face of adversity. Acevedo also inserts herself in the definition of blackness she says, “We are the unforeseen children,” which could be interpreted as a screw you to people who don’t view her as black and the whites who did not believe non-whites would sustain themselves and become successful.

Her raw and honest account also emphasizes that there is not a singular definition of blackness; it is a diverse and complex phenomenon that is defined based on a specific time and space. Afro-Latinos are typically excluded from the theory of blackness, because they did not follow the middle passage journey, which would have linked them to African American slaves. When Acevedo states, “Read our lifeline birth of intertwine/ moonbeams and starshine. We are every ocean crossed. North Star navigates our waters. Our bodies have been bridges”. Acevedo brings to light how Afro-Latinx have connections to blackness, because their history intertwines with the African slave trade. Acevedo’s discussion of her mixed and complex racial identity emphasizes Michelle Wright’s concept of blackness as an epiphenomenon, because blackness is not linear, it is fluid. It is a dynamic and “beautifully tragic mixture, a sancocho of a race history” that must be interpreted by various space times that includes multiple voices theorizing when and where blackness is.

An Examination of Queen & Slim

Queen & Slim, the 2019 film directed by Melina Matsoukas and written by Lena Waithe, tells the story of a couple, who, after an altercation with the police go on the run. What begins as an awkward first date for the couple, played by Daniel Kaluuya and Jodie Turner-Smith, turns into a journey South in attempts to evade the police. Though the film is intense and the moment of arrest looms, Matsoukas nonetheless includes scenes of quiet. There is a scene in which Queen and Slim are dancing, the world fading around them; there is another point in the film that shows Slim getting his head shaved and Queen having her braids removed; and there is another scene in which Queen and Slim hang out the car window, the ocean stretching out beside them. In the midst of extreme stress, there are nonetheless moments of beauty to be had. While the plot unfolds from the fallout of a white police officer’s actions, the film nonetheless feels like a celebration of blackness, in which humor, love, beauty, and complexity are all seen.

While the film is set in contemporary America, it weaves together incidents from various time periods, contains historical references, and bears similarity to a past in which slaves went on the run from their masters in search of freedom. In Jelani Cobb’s essay, “The Powerful Perspective of ‘Queen & Slim’,” he analyzes the events that influenced the film. In one paragraph, he writes:

Most provocatively, the incident at the heart of “Queen & Slim” is framed in the context of a May, 1973, incident on the New Jersey Turnpike, in which members of the Black Liberation Army, including Assata Shakur, were involved in a shootout in which the police officer Werner Foerster was killed. Shakur, who is referenced multiple times in the film and serves as a kind of historical inspiration for the decisions Turner-Smith and Kaluuya make after the shooting, escaped from prison, in 1979, and has remained a fugitive in Cuba for nearly four decades.1

Despite the modernity of Queen & Slim, Cobb is right in looking at how it nonetheless relates to numerous incidents involving violence against black people throughout history. In this regard, I can’t help thinking back to Michelle Wright’s book The Epistemology of Blackness in which she argues for a more non-linear, multidimensional, fluid means of thinking about blackness and its history. I would argue that Queen & Slim exists in what Wright coins “the now” or epistemological time. Wright explains, “our phenomenological manifestations of Blackness happen in what I term Epiphenomenal time, or the ‘now,’ through which the past, present, and future are always interpreted.”2 By evoking historical events, using the names “Queen” and “Slim” until the end of the film (relatively nondescript names), and including aspects that are often found in slave narratives, Queen & Slim exists in epiphenomenal time.

Queen & Slim is rich in its depiction of community and love, tracing Queen and Slim’s relationship from their first date to having to figure out how to run from the police to falling in love and to ultimately dying together. In an interview published in The Atlantic, director Matsoukas perhaps most aptly describes the relationships happening onscreen. She explains, “I also wanted to showcase black love and unity, not just romantic love. Black unity is our greatest power against oppression. What is represented on-screen is not just the love between those two characters, but the love that the community shows Queen and Slim.”3 As the couple go South, ultimately in attempts escape to Cuba, they are helped and embraced along the way. One character plays the couple “a black Bonnie and Clyde,” another tells Slim that he and Queen are safe when the two are at a juke joint, and in another scene, a black police officer lets the two escape. The film shows an intimate portrayal of black love between a young couple thrust into a situation neither of them anticipated, with a community behind them.

The penultimate scene of Queen & Slim is perhaps the most arresting and graphic of the entire film. Though in many ways this scene could be understood as the ending of Queen and Slim’s journey as they are caught by the police and fatally shot, it does not feel like a conclusion. About endings, Wright examines, “A great summing up, a grand conclusion, is simply not possible, because different moments manifest different meanings; these spacetimes can be intersected with one another, but they cannot be subsumed by one spacetime alone.”4 Matsoukas understands this inability to neatly sums things up. Queen and Slim journey continues and exists in multiple spacetimes. Their journey continues and lives on through those who remember them, as seen in the final scene with a mural of them two and children wearing shirts with their photo on it.

Lastly, the score and the soundtrack in Queen & Slim are performed by black musicians. The score, done by Devonté Hynes (also known as Blood Orange), is beautiful. Most of the tracks contain only piano, cello, and sounds from a synthesizer yet feel layered and rich. The names of the tracks themselves, such as “This Is A Safe Place,” “Bed,” “Love Theme (Photograph),” and “Kissed All Your Scars,” all emphasize the beauty and love found throughout the movie, despite of the intensity of the plot. The soundtrack too, containing songs by Solange, Lauryn Hill, Moses Sumney and Vince Staples, is varied in the sound and is a celebration of black musicians.

Through its playing with time, score and soundtrack, moments of calm, and emphasis on community, Queen & Slim feels like a celebration of black love.

1 Jelani Cobb, “The Powerful Perspective of ‘Queen & Slim’,” The New Yorker, November 27, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/the-powerful-perspective-of-queen-and-slim.

2 Michelle M. Wright, Physics of Blackness: Beyond the Middle Passage Epistemology (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 4.

3 Adrienne Green, “Melina Matsoukas’s Unflinching Eye, ” The Atlantic, December 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/12/melina-matsoukas-queen-and-slim/600907/.

4 Wright, Physics of Blackness, 94.