Resistance and Surrender are themes that have come up throughout the texts we have read in our course. Resistance typically places blackness in relation to whiteness, as something against whiteness – “resistance is, in fact, the dominant expectation we have of black culture” (Quashie 3). We see interpretations of action as resistance in texts such as The Fire Next Time, in Baldwin’s words, and A Raisin in the Sun, in Hansberry’s characters. In his book The Sovereignty of Quiet, Kevin Quashie exposes us to the idea that resistance is often something that reduces the ‘black experience’ to a monolith, and therefore using the language and logic of resistance as the prominent narrative about blackness is actually racist and reductive of black people’s experiences to their public expressions.

Quashie introduces us to the notions of interiority, intimacy, and quiet, that make up surrender. Surrender is something so individual and abstract that it is difficult to put into words – it is the exact opposite of resistance in that it is not at all performative, it is an internal process that one experiences only for oneself. Examples of surrender can be found in any of the books we read this semester, if one looks hard enough, but are especially evident in The Sovereignty of Quiet, mentioned earlier, and Looking for Lorraine, which provides us with insight into Lorraine’s inner thoughts and inner life beyond the narrative of resistance that she is often placed into. With a photograph from the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City of two black athletes who placed in the 200-meter race, Quashie shows us how an act commonly interpreted as a performance of resistance can alternatively be seen as an act of surrender. He analyzes the athletes’ body language and facial expressions to find evidence of internal processing amidst the public expression of resistance in their outstretched arms and hands formed into fists in support of black rights. Quashie’s analysis of this photograph pushes us to confront a truth in each of us — our trend to read black bodies as inherently political, expressive, resistant. Quashie pushes us to move beyond this tendency and to learn to look for and appreciate the quiet interiority that is surrender, and that renders one person’s experience individual. This section of our website seeks examples of Quashie’s ideas of resistance and surrender, and explores the relationship between the two through examples from everyday lives and media to illustrate these categories.

__________________________________________________________________________

Black Interior Photography Project created by Destiny Kearney

“A Photographic Response To The Sovereignty of Quiet by: Kevin Quashie”

After reading Kevin Quashies’ novel, The Sovereignty of Quiet, I was so moved by the text that I wanted to create my own response to his argument using an artistic mode of understanding. I decided to create a photo book for my class, in which I shared these images with members of my class. I placed the images on black pages and inserted quotes that alluded to quiet, but left it up for interpretation. This is a small blurb I included for the project.

“Quashie encourages readers to look past theorizing Blackness through the lens of resistance that is public, loud, and dramatic. He encourages readers to analyze the Black experience through the interior, or what he calls “quiet”. Quiet highlights “ones inner life-ones desires, ambitions, hungers, vulnerabilities, fears”(6). This speaks about the full range of one’s inner life that is absent from race/racism but focuses on the essence of their being. So I titled this piece The Black Interior, as I challenge myself to analyze my own interior and express it through the medium of photography.”

For this project, I directed a photoshoot in which I used self-portraiture & portraiture as a means for capturing the interior. I wanted to illustrate themes of vulnerability, ambition, desire, and fragility. To illustrate these themes, I used self-expression and the use of objects to invoke emotion. Thematically the use of artificial and natural is fluid throughout the photo series. Look at the use of flowers and lighting. What effects do these images have on you when you view them? Which aspects make you feel this way. The process itself allowed me to be vulnerable. To photograph me at home with neighbors watching and family nearby, or allowing myself to cry on camera. I needed to allow people to see the aspects of my humanness that aren’t always highlighted. Absent from race, or resistance I wanted to make myself available to the viewer primarily based on the essence of my being; my interior.

__________________________________________________________________________

Barkley Hendricks: Portraying the Interior

Being a Professor at Connecticut College, and having his collection at our art museum from July 2017- October 2017, the Bowdoin community should be no stranger to Barkley Hendricks. Barkley Hendricks is a revolutionary artist, most known for his painted portraits of black men and women in the 20th century. Influenced by dramatic court portraits of the seventeenth and eighteenth century, Hendricks painted in Grand Manner style, which essentially translates to high art portraiture.[i] The significance of this portraiture style is two-fold: it inserts the black body into art canonization, and destabilizes current hierarchies established by dominant western-centric narratives.

After traveling to Europe, Hendricks sought to fill the gaps in current canonization; he was dismayed by the lack of representation of black bodies in high art. His portraiture, modeled after the very style that traditionally excluded blackness, set out to “treat blacks with the same dignity and artistic virtuosity accorded aristocrats throughout history.”[ii] Not only does Hendricks’ portraits address issues of representation, they serve to destabilize the very systems of canonization, which systematically exclude the black body. The conscious choice to paint in a Grand Manner connotes that his portraiture subjects are reconceptualized and reimaged as classical, timeless, and dignified; manners that were previously reserved for the white aristocracy.

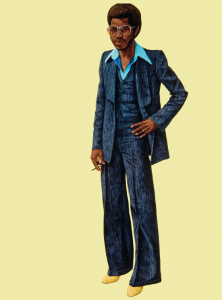

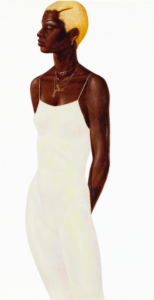

Barkley Hendricks’ piece Noir depicts a well-dressed man, in sharp detail, set against a backdrop of monochrome tan. The man looks directly at the viewer, and stands with his hand on his hip in a position of power; he has a cool aura, enhanced by his shaded glasses and cigarette, positioned between his fingers.

Hendricks’ Dancer presents a very different image. Her white dress almost blends in with the background, in striking contrast to her beautiful, dark skin. Her head is turned, exposing her profile. She has her eyes closed, in an almost reflective pose. The dancer wears a white leotard, and her hair is bleached, cropped in a short afro.

In contrast to the light, matte backgrounds the two figures are almost propelled forward. Barclays is known to capture his subjects true persona, rather than mere likeness:

“A clear depth of vision is being created. It is tempting to see this as a kind of iconicity: the projection of an interiority, an immanence, that goes beyond the external and physical reality we see.”[iii]

Barkley Hendricks’ portraits project the everyday essences of the people he captures. They epitomize Quashie’s notions of interior, and the power of quiet. Quashie argues that, “the ability of nationalism to argue for black humanity is hamstrung without a concept of interiority.”[iv] While Barkley Hendricks made it known that he rejected the label of Black Political painter, he revolutionized how the black body was depicted in painting.[v] He depicts his portrait subjects with incredible depth, stressing the importance of everyday being and portraying the full extent of one’s life, including, or rather especially, the interior.

Perhaps Hendricks’ work is best illustrated by Quashie’s words:

“Quiet is the syntax of possibility, the capacity for inner life. It is the unappreciated grace of every person who is black. Quiet is inevitable, one’s full-orbed life. Quiet is.”[vi]

[i] Anna Arabindan-Kesson, “Portraits in Black: Styling, Space, and Self in the Work of Barkley L. Hendricks and Elizabeth Colomba,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 38 no. 1 (2016): 70-79.

[ii] Ariella Budick, “Barkley Hendricks’ Black Portraits,” FT.Com, Dec 06, 2008. https://login.ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/docview/229203603?accountid=9681.

[iii] Anna Arabindan-Kesson, “Portraits in Black.”

[iv] Kevin Quashie, The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture, New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press (2012).

[v] Jazmine Hughes, “Barkley Hendricks Rejected the Label of Black Political Painter,” New York Times, December 28, 2017.

[vi] Ibid.

___________________________________________

Love Letter to Rihanna’s “Anti”

This album is everything. I am not kidding. Rihanna’s aesthetics, lyrics, and musical choices in Anti destabilize the consumption of Rihanna’s celebrity presence as a Barbados-born pop star. The album begins with Consideration, in which Rihanna sings, “Time could never me, no, no, no, no / I know you try to…I got to do things my own way darling / will you ever let me? Will you ever respect me?” Her lyrics confront so many themes we covered in this class: expanding past the linear and Western concepts of time, the radical potential of black artists creating art for themselves, and not as representatives of a race, and the liberating empowerment of a black woman demanding respect. In this album, Rihanna unapologetically defies all expectations, choosing instead to craft her own narrative, unintelligible to those who do not seek to understand. Her identity is created on her own terms, and this album does not attempt to create a cohesive and easily digestible portrayal of who she is. As a project, Anti is layered and complex, exploring and experimenting with multiple genres, styles, and influences. Anti is beautiful in its decision to remain undefined, purposefully claiming ambiguity over marketability or even likability. Anti-linear, anti-colonial, anti-yours. Anti does not exist for reviewers, or album sales, or even for me. Anti just exists for itself.

In our class, we thought critically and deeply about the concept of interiority as a framework for understanding black identity and individuality. Challenging the racist assumption that black people are monolithic necessitates comprehending the expressive and private ways in which black people nurture a productive sense of self. Art, through literature, poetry, and music, are particularly powerful mechanisms through which black people produce meaningful inner worlds. The author Kevin Quashie draws on the notion of quiet as a transformative act that goes beyond resistance within black culture, and pushes readers to fundamentally trouble our preconceptions of what black people resisting looks like. He illuminates the nuance and depth of black identity when black people’s private worlds the ideas and dreams the public does not see – are taken seriously as sites of meaning. What is revealed when we move beyond resistance as the dominant discourse for understanding and reifying black people’s bodies, art, and lives?

Anti is an album that cannot be fixed. The album consists of multiple genres, ranging from dancehall-influenced “Work” to a blues-inspired “Higher” to the Travis Scott-produced “Woo” to the little ditty “James Joint” to the Tame Impala-sampled “Same Ol’ Mistakes” and concluding with “Sex With Me,” a shameless and joyful celebration of sexuality and pleasure. As a whole, the album operates completely outside of a dichotomous system that seeks to easily label music and identity. In fact, Anti rejects linearity or cohesion, which earned the album largely negative and confused reviews. People did not understand the point of the album, so different from her earlier pop/dancehall/reggae albums. As if musicians are not, like all of us, in constant states of transition, changing and growing with new inspirations and encounters. The album is experimental, exploratory, and deeply interested in what feelings can be produced from collaborative and expansive approaches to music-making. Anti demonstrates what is possible when artists transcend predictability or consistency in favor of liberation. The album is anti-resistance because the album does not even try to play by the hegemonic rules of what kind of music a popstar should make. Those rules were only going to hold Rihanna down.

The scholar Stuart Hall asserts that Anti is radically post-colonial and undeniably Caribbean precisely for its refusal to be defined and categorized. He states that Anti exemplifies “that resistance to conformity, that resistance to needing and pleasing and placating the global marketplace” by situating the album’s meaning within Rihanna’s specific context. He continues, “Anti is actively telling you, song after song, that it’s not trying to fit.” Rather, as Rihanna reminds her listeners, “You needed me / to give a little more, and feel a little less,” a line that applies to a former lover or, perhaps, the music industry, one that thrives on the exploitation and commodification of black art and bodies. Don’t get it twisted – Rihanna’s agency is all her own, and her art is within her own hands.

Anti is sexy, angry, powerful, desperate, flirty, nostalgic, lonesome, and flippant all at once. Situated within the larger post-colonial context of contemporary America, Rihanna’s album goes beyond the objectifying tropes of an exotic Barbados star and represents a black woman making art for art’s sake. The album is material culture but does not attempt to represent black culture. Anti is a glimpse into Rihanna’s interior world, all the complex layers and beauty that shift and transform throughout space and time. What a force to be reckoned with.

Colin Kaepernick’s Inner Life

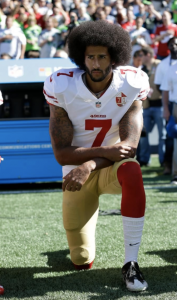

Colin Kaepernick quickly became a national symbol of black resistance and advocacy for black rights when he began kneeling during the National Anthem in the 2016 NFL preseason. His actions sparked a national debate, with conservatives claiming kneeling during the National Anthem unpatriotic, disrespectful, and hateful, and liberals praising his action as an admirable form of protest to raise awareness about the oppression of POC in the US. Kaepernick’s kneeling sparked a chain of other celebrities and athletes coming out in support of him or his message, and many even kneeled during the National Anthem in their own sporting events. Kaepernick’s protest, therefore, and in extension, Kaepernick himself, became a symbol of the national conflict about race between conservatives and liberals. Within this climate, it is easy to look at Kaepernick’s actions as purely performative and political. I argue, however, that the tendency to view the action as only political is a choice to ignore the personal intimacy and personal meaning of the action that Kaepernick obviously feels. In other words, to focus only on the resistance in Kaepernick’s statement of protest is to deny the wholeness of his lived experience, to paint over the moments of surrender that are present in his facial expressions, in the direction of his eyes, in the quiet solidarity of the teammates who choose to kneel beside him.

Using the two photographs of Kaepernick above, I provide an alternative analysis other than the common narrative of resistance. One could find evidence of resistance in Kaepernick’s strong, symmetrical stance of kneeling during an anthem where we are socialized to stand, remove hats, and direct our attention to our country’s flag. However, surrender can also be found in this stance, in his shoulders curled inward ever so slightly, arms folded one over the other and resting on his knee, and in his somber facial expression with his eyes gazing at the ground. He rests his arms on his knee, and I wonder what he is thinking of. I wonder if he rests that way because he feels he is the only one who can support his own weight. In his eyes, I look for his emotions. He seems pensive; at the very least, it is obvious that his action is not done purely as an act of resistance. It is an action that holds serious personal meaning to him as well, a moment of quiet introspection, an interior experience as well as an exterior statement.

I think Quashie’s ideas of resistance and surrender, when applied to Kaepernick’s protest, provide us with insight into a way we can view protests in general. It is our tendency to view protests such as Kaepernick’s as purely public performances, as extremely clear external statements. Maybe the lesson we should take from this is, that behind every public expression is an interior process, a complex system of emotions, values, life experiences, and learned patterns of behavior. This may seem obvious, but it’s important to acknowledge it, otherwise individuals’ acts are lost in a sea of politics, and bodies are rendered exclusively political. The politicization of black bodies neglects the interior complexity that black individuals possess, and renders their individuality, interiority, and surrender, invisible.

___________________________________________

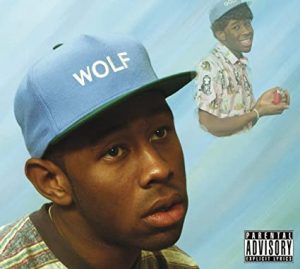

Analysis of “IFHY” by Tyler, The Creator

When I first started listening to Tyler, The Creator, I always dubbed him as the “unconventional black”. Sure, he rapped but his songs were emo, expressive, and slightly psychotic. He was nothing like the black artists I was listened to at the time and I loved him for that. After reading Kevin Quashie’s piece, Sovereignty of the Quiet, I now realize that Tyler, The Creator is resisting the dominant expectation of blackness and black masculinity. Quashie defines the interior is the reservoir of a persons’ quiet and allows for “creativity beyond the public face of stereotype and limited imagination”. In the song “IFHY,” Tyler engages with the quiet and surrenders to his interior as he publicizes his internal monologue about how much he hates yet loves a girl who wronged him with another man. Tyler is not resisting blackness as a whole but rather surrenders to his interior desires, fears, thoughts, and more which makes his blackness unique.

The song opens with a few keys from a mortuary pipe organ, which suggests that a part of Tyler has died because of how heartbroken he is over the situation. Throughout the song, Tyler explores what it means to be human, abstract from expectations of blackness and black masculinity. It is not socially acceptable for Black men, in particular, to be vulnerable and explore the full range of their emotions; especially in a public way. Tyler, however, dives into his interior and explores everything that makes him human in order to effectively deal with his issues. Specifically, Tyler states:

“Can we add some more color,

Um, like some more, yellow? …

I f****ing hate you. But I love you.

I’m bad at keeping my emotions bubbled

You’re good at being perfect

we’re good at being troubled”

Tyler demonstrates how the quiet is extremely dark and understood as staying away from because of the fear of being vulnerable. Asking for yellow or something to brighten up the room could signify the desire to lighten the mood and not deal with his feelings. However, he is not given the chance to stray away from his emotions. In this section, Tyler also demonstrates how the interiority is dynamic and conflicting because he is still in love with the girl, yet feels wronged by her. I believe that if he had not surrendered to his interior consciousness he would not have entertained the possibility of him still having feelings for her. This would have hurt him more emotionally since he does not effectively engage with his emotions.

One of my favorite verses in the song is:

“Cause when I hear your name

I cannot stop cheesin’

I love you so much that my heart stops beatin’

when you’re leavin’ and I’m grievin’

and my heart starts bleedin’”.

In this verse, Tyler experiences conflicting emotions and we can tell that it is a little uncomfortable for him to be exploring this side of himself. But he continues to engage since he has already fallen down the rabbit hole. Tyler has no control over his feelings and the pace of his voice sounds as if he is spiraling unable to maintain his feelings. His engagement with the interior renders him vulnerable but uses this space to explore what it means to love and be human abstract from public expectations rendered on him as a black male.

Once the song reaches the bridge, the beat becomes less gritty and dark which signifies how surrendering to his interior, Tyler finds some resolve with the situation. In this part of the song, Tyler bargains and tries to find ways that will make the girl stay with him. Specifically, he states:

“Look, I wanna strangle you,

‘til you stop breathing…

Spend the rest of my life, looking for air.

So you can breathe, or we can die together,

you and me”.

His resolve is not what one would want to hear and would ultimately label Tyler as psychotic and insane, which agrees with Quashie’s definition of the quiet as impulsive, dangerous, and shifts to life’s stimuli. He is definitely on some Romeo and Juliet type shit in his interior. Tyler needed to engage with his interior to gain a better understanding of his current situation. If he had not, Tyler would have fallen into the trap of performing blackness rather than being black in his own form. His private, yet public, expression of the interior allows Tyler to regain power and comfort within himself since he does not conform to expectations of blackness and black masculinity.

___________________________________________

Carrie Mae Weems, The Kitchen Table Series, 1990

In the Kitchen Table Series, Carrie Mae Weems, explores race, gender, sexuality, love, friendship, loss, power, and motherhood. All photos are black and white which neutralizes the situation and her identity as a black person; however, directly above the kitchen table is a bright central light that draws attention to the political and intimate messages packed into the image. The lighting forces the audience to think about Weems as a person, not her association with blackness. In this series, Weems’ engagement with the quiet and surrender to her interior resists what it means to be a black, cis-gendered woman in America. Discussing the series in general terms does not give the project justice. For that, I will focus on the piece, “Untitled: Woman Standing”, available in the gallery.

For Weems, the kitchen is a metaphor for her quiet. The kitchen has a dual role: it is a place that women are forced into because of patriarchy, but also a place that allows her her to explore her inner desires, thoughts, ambitions, and more. Weems stares into the camera as she stands at the head of the kitchen table in a power stance. Her sleeves are rolled up and both of her hands are firmly placed on the table with a slight bend in her elbow leaning in towards the viewer. During the time these photos were taken, women claimed their space as the family caretakers, submissive to their husbands who were rarely operated in public. However, in this photograph, Weems rejects the idea of women being forced into domesticity and submissive to men by standing at the head of the table. When the kitchen functions as her quiet, Weems is in charge and has total control over how she and her identities are represented.

In addition to taking her seat at the table to defeat the patriarchy, Weems unapologetically takes a seat at the table to promote and counteract white feminism. In the photo, Weems’ sleeves are rolled up in an almost masculine way that reminds me of the iconic Rosie the Riveter “We Can Do It!” poster. Rosie the Riveter’s image was used to promote feminism and introduce women to the American workforce. However, in this feminist movement, only white women’s voices were heard and taken seriously; pushing black women further into domesticity. In this photo, Weems promotes black feminism by opposing Rosie’s’ white feminism through engagement with her interior. This emphasizes her intrinsic desire to be free from the social constraints that lock her inside the kitchen because of her intersectional identity as a black person and as a woman.

Throughout the series, Weems explores her freedom inside the kitchen, a place used to further oppress her. The quiet, a place that is typically shunned and/or receives little recognition by the black community. By engaging with the quiet, Weems finds internal solace within external turmoil. She can be uniquely and unapologetically black. Weem’s stance in this photo is powerful in that she rejects notions of her being forced into domesticity and actively claims the space as her own where she can be and explore herself in a variety of ways. In this sense, Weems’ quiet is a form of resistance, but also her peace.