Kathleen Megan

The ethnic studies movement came in Connecticut as a response to a failing curriculum. For years, Connecticut has had a troubling achievement gap between white students and students of color in various subjects, with Asian students being exceptions to this trend. For example, as of 2019, only 36 percent of Hispanic/Latino students and 34 percent of African American students tested at grade level for English, compared to 70 percent of white students in grades three through eight. Asian students were the highest performing group (Megan, 2019). To tackle this issue, representative Bobby Gibson introduced the idea of incorporating ethnic studies courses into Connecticut curriculums. He argued that students of color would be less likely to understand and remain engaged with lessons if they could not see themselves represented within them. In 2019, he endorsed a bill that would make African American studies and Latino American studies a requirement of every school district’s high school curriculum starting in 2021. Though students would not be required to take these courses, they would be available as electives. In the hearing for the bill, he held up a new history textbook on American history, paperclipping all the pages together that dealt with African American history. The clipping was less than a quarter of an inch thick. With such powerful imagery, the bill quickly passed through to the senate, with a vote of 122 to 24. (Megan 2019)

While it was originally representative Gibson that introduced ethnic studies to Connecticut education policy, it was the student and community organizing around the bill which led to its victory. A large part of the support was from groups from New Haven, a city in which, according to U.S Census Bureau estimates, over 50 percent of the population identifies as a person of color (U.S Census Bureau, 2020). In 2009, New Haven Public Schools launched the School Change Initiative, which aimed to close the achievement gap and ensure that students were on the path to higher education (U.S Department of Education). Though students have made gains, recent scores show that the gap persists and that the district lags behind state scores (Tabio, 2019). Seeing the inefficiency of the high stakes testing approach, students and community groups have been advocating for curriculum reform for some time. The Gibson bill proved to be the perfect opportunity to share their support and the reasoning behind culturally relevant pedagogy.

The Groups Involved

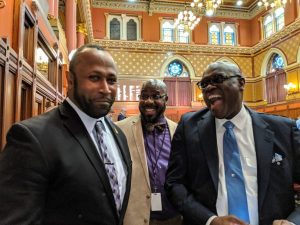

Ryan Lindsay

One of the main groups behind this initiative was Students for Educational Justice, a non-profit organizing organization that aids New Haven youth in fighting for educational reform while also teaching them the basics of organizing and community planning. They began working with Representative Gibson and Senator Douglas Mccrory to work out the logistics of the bill and ensure its success by proposing amendments to the bill. They also connected with other organizations within the state to raise awareness about the proposal, ask those organizations to provide testimonies supporting the bill for the upcoming Senate hearings, and had student representatives within the organization share their testimonies at these hearings (Students for Educational Justice, 2020). Most testimonies came from fellow students of varying grade levels and schools throughout the state (Gellman, 2019).

Citywide Youth Coalition

Another group that was heavily involved was the Citywide Youth Coalition, a network of student-led organizations, parents, community activists, and “youth-serving professionals” seeking to create a community in which all youth can succeed. They argue that the way to do this is by connecting youth organizers and activism efforts across the state to build a network for youth empowerment and a space for youth leadership. They helped form connections between Students for Educational Justice and other groups fighting for similar causes, such as Hearing Youth Voices. They also offered trainings on undoing racism and the basics of youth organizing to best equip them to continue to make change (Citywide Youth Coalition). They went to senate hearings on the bill to cheer students on (Gellman, 2019).

The Elm City Undoing Racism Organizing Collective (UROC), a group of organizers and educators working for social change in New Haven, also worked closely with these groups. They helped host the undoing racism and community organizing workshops. Their focus was to teach students and community partners what racism was, where it came from, how it worked, and what could be done to build a more equitable city (Elm City UROC). They were also present at hearings to provide support (Gellman, 2019). It should be noted that neither this group nor the Citywide Youth Coalition directly told students what to do. They instead served as supports for the students as they figured out how to organize and fight for a sometimes seemingly unreachable goal.

Results

Lucy Gellman

Thanks to the collaboration of these groups and the unwavering commitment from youth to seeing that the bill gets passed, by the time the final senate hearing came, the support for the bill was substantial. Over 200 people were in attendance and over 100 testimonies were given from students, educators, and politicians; no one testified against the bill. Unsurprisingly, the bill passed. By 2022, all Connecticut high schools must offer elective courses on African American, Puerto Rican, and Latino history (National Education Association, 2019). After so much work, community members and activists left the hearing feeling victorious and empowered. For students, the victory made them feel like they had ownership of their education (Students for Educational Justice, 2020).