This is a research and awareness synthesis project by Emily Talbot ’16, a junior at Bowdoin College, Brunswick, Maine, in the seminar class “Urban Education.”

Before 1938, ethnic studies were not even remotely considered as part of the standard American education for high schoolers. Yet the 21st century has seen an increasing controversy over ground-up calls to action for increased representation of multicultural perspectives embedded into regular curricula nationwide. As reported by Juan Castillo for NBC News Latino this November, “‘In many respects, ethnic studies is sometimes treated like a convenient academic add-on,’ said Nolan Cabrera, an assistant professor in the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona. ‘What this [research linking Mexican American Studies with higher academic success] is demonstrating is that ethnic studies in and of itself represents real education.’”[1] Cabrera spearheaded Tucson’s ethnic studies program, which, like the Mexican American Studies programs in Texas, has come under fire for teaching with a culturally exclusive mentality.

House Bill 2281 was a court-mandated ban on Arizona’s Mexican American Studies (MAS) Program in 2010, stating, “A school district or charter school in this state shall not include in its program of instruction any courses or classes that either: 1. Are designed primarily for pupils of a particular ethnic group. 2. Advocate ethnic solidarity instead of the treatment of pupils as individuals.”[2] Although this ban was ruled constitutional in early 2014, Arizona’s large Diné population still received federal funding for Indian instruction programs and native studies, but across the southwest.[3] The cutting of ethnic studies in Los Angeles public schools—schools and curricular organizations concentrated in the southwest, but also in New York and Chicago, in the past decade have dedicated themselves to the explicit empowerment of students typically marginalized by a one-sided history and general curriculum. A counter-insurgency against Arizona’s constitutionally affirmed ban as of 2014 called Librotraficante, which smuggles Latino-written books into the state, captures the urgency of political action needed to make ethnic studies an expanded norm instead of a rare exception in schooling.

According to Anthony Cody from the blog “Living in Dialogue,” “On November 19, the Los Angeles Unified School District school board voted to make Ethnic Studies a required course for every high school student. This action has inspired a similar move in San Francisco, where the school board will vote on an ethnic studies proposal on December 9. Backers of the initiative are asking supporters to wear red and show up to a rally prior to the board meeting.”[4] The El Rancho, San Francisco, and Los Angeles Unified School Districts have instituted an ethnic studies mandate as of this year, and students and educators pairing with community applications of their learning have led to the foundation of several multiculturally-focused schools. In school districts like Los Angeles, in which 90 languages are spoken and the majority of students are non-white, ethnic studies is not an exclusive endeavor but a an appropriate, culturally reflective and balanced approach to establish applicability in education for all students, especially those usually left out of traditional U.S. History textbooks. Tala Khanmalek writing for The Feminist Wire attests to the power of reading an autobiography of Assata Shakur: “It is no wonder that Ethnic Studies is under nationwide threat and banned in Tucson schools. Classes like African American Lit treat education as it should be treated in every discipline at every level of study: a source of empowerment in the service of social justice.” [5] Small, community-oriented schools—both elementary and secondary—in cities like Brooklyn, Oakland, and Flagstaff have also been founded in the past decade and a half to solidify the very ethnic solidarity vilified by opponents of multicultural studies.

Bambu, Los Angeles-based social-protest rapper, responds in 2013 to Arizona’s book ban of 2010

[1] Castillo, Juan. “Can Ethnic Studies Improve Student Achievement? Researcher Says Yes.” NBC Latino. 24 Nov. 2014.

[2] State of Arizona House of Representatives: Rep. Montenegro et al. HB2281. 2010. http://www.azleg.gov/legtext/49leg/2r/bills/hb2281p.pdf

[3] Tirado, Michelle. “Despite Arizona’s Ethnic Studies Ban, Students Can Still Enroll in Native Programs.” Indian Country Network. 18 May 2012.

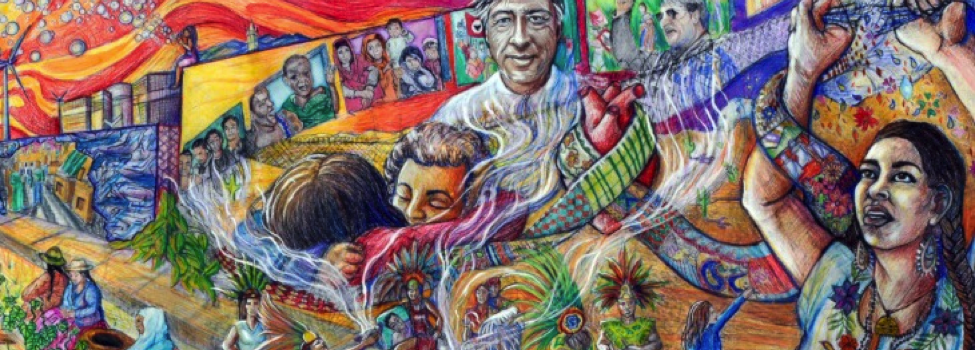

[4] Cody, Anthony. “Ethnic Studies Gains Strength in Los Angeles and San Francisco.” Living in Dialogue. Blog. Credit for header photograph of mural.

[5] Khanmalek, Tala. “How Assata Shakur Changed My Life: The Importance Of Ethnic Studies Curricula In High School And Beyond.” The Feminist Wire. 20 May 2014.

Credit for header photograph “Stop Hate: Educate”: Stencil by Joel “rage.one” Garcia. http://www.altoarizona.com/images/joel_rageone_garcia_stencil.jpg

Credit for header photograph of protestors: Librotraficante’s web page “TX SBOE Sabotages Ethnic Studies Textbooks” http://www.librotraficante.com/