The Problem with the Second Wave of Gentrification by Alan Ehrenhalt

In Alan Ehrenhalt’s article The Problem with the Second Wave of Gentrification, Ehrenhalt compares the first wave of gentrification in major cities like Chicago, New York, San Francisco, and Chicago during the 1990s with the second phase of gentrification occurring today. He opens his piece with a definition of the term hipster from the 1950s-a person living “with death as an immediate danger, to divorce oneself from society, to exist without roots, to set out on that uncharted journey into the rebellious imperatives of the self”-and compares it later to the romanticized, coffee-shop hipster conceptualized today.1

The evolution of the term hipster leads into a discussion about gentrification’s development across the first wave in the 1990s and into its second today. In the 1990s, middle-class gentrifiers were largely gays, artists, and rebellious figures who settled into abandoned or rundown districts.2 However, these areas were not held as communities by city residents; thus the fight over the first gentrified areas of major cities did not involve displacement or control over the area. As property values increased after this initial wave of gentrification, urban areas began to be of high demand from middle-class individuals and families, and individuals began to expand outward from city centers into other urban communities.3

This second wave of gentrification pushed into predominantly low-income, minority communities of major cities like Fort Greene in Brooklyn and Logan Square in Chicago.4 This resulted in fights between original inhabitants and newcomers to urban communities where gentrifiers were seen as having “Christopher Columbus syndrome.”5 Suburban areas surrounding major cities also became more appealing to gentrifiers through real estate investments and building community centers which further displaced low-income and minority individuals and families from their original homes. Thus, as Ehrenhalt depicts in his piece, in order to keep up with White demand for urban spaces, low-income, minority neighborhoods began to be attractive for gentrifiers looking to capitalize on property values within the city.

Although Ehrenhalt clearly highlights the negative effects of gentrification on urban communities, he also lays out some positive aspects of gentrification within urban spaces. He notes decreases in crime and additional businesses within these gentrified areas as overall improvements to urban neighborhoods.6

Income Inequality and Urban Displacement: The New Gentrification by Karen Chapple

Karen Chapple applies an economic lens to the issue of displacement in urban areas in her article, “IncomeInequality and Urban Displacement: The New Gentrification.” In the beginning of her essay, she argues that gentrification and its subsequent neighborhood displacement is not spurred simple “life style choices,” but rather that it is symptomatic of a larger income inequality crisis due to changes in the labor market.7 Chapple states that the problem of displacement roots from a rise in technological innovation, a decline of unions and a decrease in labor demand for manufacturers and service workers.8 This need for more educated, specialized workers in urban areas results in a push out low and middle-class community members and an entry of gentrifiers into these neighborhoods.

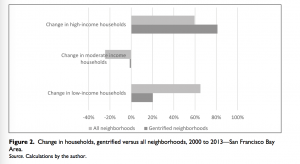

Chapple used data collected by the Urban Displacement Project about demographic changes in the San Francisco Bay Area to further illustrate her argument of gentrification and displacement as income inequality problems. Over 10% of Bay Area households lived in neighborhoods undergoing gentrification or inhabit neighborhoods that are experiencing displacement pressures.9 Due to housing price increases, low-income households, especially in neighborhoods largely inhabited by people of color, either can no longer afford to live in their communities or are excluded from entering into units that were formerly for low-income housing by were converted to a higher income class.10These conclusions reaffirm the notion that gentrification and its subsequent displacement disproportionately affect low-income, minority communities.

In her analysis, she also found that gentrification in the San Francisco Bay Area resulted in increases in the amount of low-income and high-income households of gentrified neighborhoods but in decreases in the number of middle-income households.11

12

12

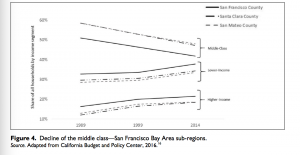

13

Therefore, both low-income and middle-income households experience displacement due to urban development meant that captures only high-income demand and use. This need to create retail and housing for only upper-class individuals stem from high costs of land and construction; for any urban development project to be profitable, contractors need to reach into higher price ranges to get their highest return.14 Chapple notes that without change in current land and construction costs, it will never be profitable to build low or middle-class housing in urban communities.15

In order to prevent future community displacement for low-income and middle-income households, Chapple believes in adopting more creative government policies to simultaneously house more individuals at lower costs and to maintain the incomes of individuals in urban neighborhoods.16 This more holistic approach can prevent more income disparity amongst different social classes and grant urban communities members of lower income statuses more security in their housing.

Follow these links to access the articles for your own eyes!

The Problem With the Second Phase of Gentrification

Income Inequality and Urban Displacement: The New Gentrification

References:

1 Ehrenhalt, A. (2016, February). The Problem With the Second Phase of Gentrification. Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://www.governing.com/columns/assessments/gov-gentrification-second-phase.html

2 Ibid

3 Ibid

4 Ibid

5 Ibid

6 Ibid

7 Chapple, K. (2017). Income Inequality and Urban Displacement: The New Gentrification. The New Labor Forum, 26(1), 84-93. Retrieved May 1, 2017, from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1095796016682018

8 Ibid

9 Ibid

10 Ibid

11 Ibid

12 Ibid

13 Ibid

14 Ibid

15 Ibid

16 Ibid