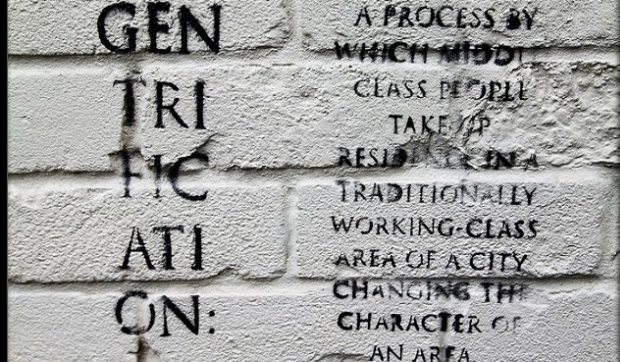

Defining Gentrification in the Context of Public Schools

Gentrification is the influx of white, middle-class individuals and their resources into urban areas with a minority, low-income population. After the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) ruling and the Civil Rights Act of 1964, many white urban dwellers responded to the desegregation of urban public schools by fleeing the city to suburban areas.This “White Flight” epidemic to suburban areas changed the racial and socioeconomic characteristics of cities to this day , and not only built a financial wall between urban and suburban communities but also eliminated the hope of upward mobility within many urban areas.1 In order to replenish abandoned city communities with the resources lost after “White Flight,” policymakers have instituted market-based education reforms in urban school districts to make the area more attractive to young professionals and increase their movement to urban areas.2 Neoliberal policies, including school choice, school closures, and charter school initiatives, promote accountability in the public school system and create “more choice” for families to seek out and decide on the best school to meet the individual needs of their child.

In theory, the increase in interest in urban areas by white families and middle-class families also appears to be an opportunity to finally integrate urban schools (it encourages look like the economic and educational revamp needed in urban communities within the eyes of local school and government officials. However, in practice, neoliberal education reforms cause a two-tiered system “haves” and “have nots” in public education, where families with privilege and resources are able to utilize these free-market principles to make gains in the public school education system and families of color and low-income are disadvantaged by the system. Thus, gentrification spurs on education reforms that also creates displacement even within classroom settings.

What Does Gentrification Mean For the Community?

The following YouTube clip entitled “Mission Playground is Not For Sale” exemplifies the different perceptions of communal space shared by original neighborhood residents and new-to-the-area gentrifiers. The gentrifiers argued that, because they had paid to use the soccer field, they were entitled to play their league game at this time, even though other residents, including neighborhood youth, had been occupying the field to play 7 v. 7 soccer. Led by their coach, the original community members stated that the field had never been for sale, and the field should, as it’s always been, be utilized on a first-come-first-served basis. During the video, the confrontation escalates to a point where the middle-class, white male gentrifiers remark “who gives a sh!*” about the community.

This video touches upon the disconnect and conflicting interests between the original inhabitants of urban spaces and the gentrifiers that are now also occupying the neighborhood. This type of frustration can also be felt by these initial members of the community within gentrified public school systems.

How Does Gentrification Cause Students and Their Families to Lose Agency in the Public School System?

Within the public school system, families with privilege and resources are able to maximize the neoliberal policies built in the system to receive the best educational experience for their children. However, in doing so, children of color and children of low-income households actually lose agency in the system because they are left to choose and attend schools in the options leftover from this first round of privileged decisions. Therefore, families with inherent political capital, knowledge, time, and resources capitalize on market-based reforms, including school choice, school closures, and charter-based initiatives, while the longtime students of the urban communities must work with limited options available to them within and outside of urban public school systems. And gentrification provides an impetus for policy-makers to

How Do Market-Based Reforms Brought Into the System by Gentrification Further Marginalize Low-Income Families and Families of Color?

SCHOOL CHOICE programs appear to build agency on the behalf of families to decide which public school institution best fits the unique needs of their child. Expanding pre-existing school choice programs can improve the reputation of urban public schools and, thus, increase the influx of white families and middle-class families into the urban school system.3 Privileged families are able to explore educational options both within and outside of urban areas. However, minority families and families of low socioeconomic classes are restrained by resources to remain within urban centers and use neighborhood schools.4

Marginalized families may not have knowledge of all the alternative options available to them in the urban school system due to various factors like language barriers, time commitments, and resource constraints. Without this knowledge, minority families and low-income families accept their local neighborhood as their sole option, missing out on additional choices that privileged families would utilize.5 Although school choice programs do create agency and options for white families and middle-class families, market-based reform measures diminish the choices available for minority families and families of low-income.

Even when school choice programs are limited to enrollment in the neighborhood schools corresponding to residence, the neighborhood public schools begin to segregate and stratify to the demographic composition of its urban communities.6 This type of enrollment makes certain neighborhood schools accessible for only white, middle-class, gentrified families, due to the community’s residential value and financial barrier that comes with living in the neighborhood.7 Therefore, the implementation of neighborhood school enrollment can cause segregation and stratification in urban neighborhood schools because of the privilege needed to live within certain residential spaces.

According to market-based reform measures, SCHOOL CLOSURES stem from a public school’s failure to perform to a profitable level. Rather than maintain a cost-intensive school within a marketplace system, local government and school officials close neighborhood schools to create space opportunities for real estate developers, charter school initiatives, or retail venues, which can improve gentrification to the urban area.9 Despite being seen as part of the gentrification process, school closures represent one of the highest degrees of state abandonment and capital accumulation in neoliberal policies.10 This process of eliminating an “inefficient” school from the marketplace of public schools causes state disenfranchisement and emotional harm to families and community members that see the school as an integral part of their greater community.

School closures have a lasting negative impact on community members and students within the affected neighborhoods and may have lasting effects on the students’ perception of school. The emotional ramifications of school closures upon students and community members heighten the sense of state abandonment felt within minority and low-income communities, especially African American communities that suffer from the most numerous school closures.11 Many students suffering from school closures move on to schools of equivalent or even lower value; this makes their experience with school closure more difficult because they can’t understand why their school was closed to begin with.12 Many students feel dehumanized and uncomfortable within the environment of an educational institution due to the fear of its elimination from their daily lives.13 School closures also destabilize the greater community as a whole because neighborhood schools are often envisioned as some of the most stable institutions in low-income, minority areas.14 Thus, although school closures provide white, middle-class communities with additional funding for their success, their actions largely disadvantage minority families and low-income families statistically are impacted by school closures than white families and middle-class families.

CHARTER SCHOOL INITIATIVES also exemplify the further marginalization of disadvantaged groups by adding new educational opportunities for white families and middle-class families while excluding minority students and students of low-income families from participating in them to the same degree. In theory, charter schools should provide all families with a lottery opportunity for enrollment. However, because gentrified families have “more time, resource, and cultural capital” to engage in the lottery process, they are more likely to apply and be admitted into the best performing charter schools.15 Charter school initiatives disadvantage minority students and students of low-income families by limiting the number of quality public and charter schools available to them within the public school system.16 Because minority and low-income families do not possess the time, money, and resources to navigate the charter school lottery process, these marginalized families continue to receive limited resources and opportunities, directly conflicting with the message in Brown (1954) and the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Concluding Remarks About Gentrification and Urban Public Schools

So what role does gentrification play in urban public schools today? The arguments that are pro-gentrification in public policy today contain messages reflected in pro-market-based reform measures to the education system today; focused on Civil Rights propaganda and a “savior” mentality, the argument behind gentrification and neoliberal education reforms is to provide additional opportunities and improvements to disadvantaged urban communities. However, the ultimate irony associated with gentrification and market-based educational reforms is that the incorporation of gentrification and neoliberal policies into urban communities causes actual displacement and loss of autonomy over the community for individuals that had occupied the urban space, predominantly low-income, minority households, long before the influx of the white, middle-class gentry. Therefore, gentrification maintains and increases stratification and segregation in urban communities, even in urban public schools with the sort of educational reforms it brings about.

References:

1 Noguera, P. (2015). “Chapter 2: The Social Context and Its Impact on Inner-City Schooling”. In B. Picower & E. Mayorga (Authors), What’s race got to do with it: How current school reform policy maintains racial and economic inequality (pp. 23-41). New York: Petr Lang.

2 Wilson, E. K. (2015, July 26). Gentrification and Urban Public School Reforms: The Interest Divergence Dilemma. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2635532

3 ibid

4 DeSena, J. N. (2006). What’s a Mother To Do? Gentrification, School Selection, and the Consequences for Community Cohesion. The American Behavioral Scientist, 50(2), 241-257.

5 Ibid

6 Wilson, E. K. (2015, July 26). Gentrification and Urban Public School Reforms: The Interest Divergence Dilemma.

7 Ibid

8 Lipman, P. (2015). Chapter 3: School Closings, the Nexus of White Supremacy, State Abandonment, and Accumulation by Dispossession”. In B. Picower & E. Mayorga (Authors), What’s race got to do with it: How current school reform policy maintains racial and economic inequality (pp. 59-76). New York: Petr Lang.

9 Ibid

10 Ibid

11 Ibid

12 Ibid

13 Ibid

14 Ibid

15 Wilson, E. K. (2015, July 26). Gentrification and Urban Public School Reforms: The Interest Divergence Dilemma.

16 ibid