Ever since the rise of the American public school system in the mid-nineteenth century, communities have organized themselves in order to advocate for a wide range of school reforms. However, education and community organizing are also related on a much more fundamental level. How, if at all, are education and organizing related? Can education lead to organization? Is organizing itself educational? And what is meant by “education” in each of these cases? Throughout the years, different organizers and educators have made sense of the relationship between education and organizing in different ways. The views of several organizers and educators are explored below.

Horton: Educating and Organizing as Distinct Roles

Myles Horton of the Highlander Folk School believed that his primary responsibility as an educator was that of empowering others through experiential methods, and he believed that the roles of educator and organizer are often in conflict (Horton & Freire, 1990). In particular, he believed that organizers must prioritize using their skills and knowledge to effectively solve problems, while educators should empower others to develop their own strengths and skills. In order for education to be empowering, according to Horton, the educator must allow the people to discover the value of their own experiences and become experts in their own right.

Myles Horton of the Highlander Folk School believed that his primary responsibility as an educator was that of empowering others through experiential methods, and he believed that the roles of educator and organizer are often in conflict (Horton & Freire, 1990). In particular, he believed that organizers must prioritize using their skills and knowledge to effectively solve problems, while educators should empower others to develop their own strengths and skills. In order for education to be empowering, according to Horton, the educator must allow the people to discover the value of their own experiences and become experts in their own right.

Freire: Educating and Organizing as Cyclical Processes

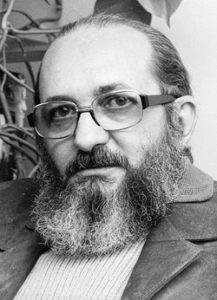

Meanwhile, Paulo Freire, who worked in rural Brazil, understood organizing and education to be more cyclical and codependent than did Horton (Horton & Freire, 1990). To Freire, the act of organizing was educational, both for others and for the self: “It’s impossible to organize without educating and being educated by the very process of organizing” (p. 121, emphasis in original). Unlike Horton, Freire was less concerned with a strict distinction between the role of educator and that of organizer but rather viewed the two roles as intrinsically related.

Meanwhile, Paulo Freire, who worked in rural Brazil, understood organizing and education to be more cyclical and codependent than did Horton (Horton & Freire, 1990). To Freire, the act of organizing was educational, both for others and for the self: “It’s impossible to organize without educating and being educated by the very process of organizing” (p. 121, emphasis in original). Unlike Horton, Freire was less concerned with a strict distinction between the role of educator and that of organizer but rather viewed the two roles as intrinsically related.

Baker: Educational, Group-Centered Organizing

Ella Baker, a leader and change-maker during the Civil Rights Movement, had a similar perspective to that of Freire, arguing that respect for the knowledge of the people is critical to the process of organizing. To her, engaging in organizing, especially in the form of direct action, “was always a part of an overall strategy of empowering people, never an end in itself” (Mueller, 2004, p. 87). She was focused not on the short-term successes of organizing but on the long-term processes of education and empowerment. She made it her goal to help people reach the understanding that they themselves were powerful and capable of creating change, and she promoted the idea of “group-centered leadership” where the voices of all could be heard (Mueller, 2004, p. 85). Thus, she too saw organizing as a process that—when done right—could be profoundly educational for those involved.

Ella Baker, a leader and change-maker during the Civil Rights Movement, had a similar perspective to that of Freire, arguing that respect for the knowledge of the people is critical to the process of organizing. To her, engaging in organizing, especially in the form of direct action, “was always a part of an overall strategy of empowering people, never an end in itself” (Mueller, 2004, p. 87). She was focused not on the short-term successes of organizing but on the long-term processes of education and empowerment. She made it her goal to help people reach the understanding that they themselves were powerful and capable of creating change, and she promoted the idea of “group-centered leadership” where the voices of all could be heard (Mueller, 2004, p. 85). Thus, she too saw organizing as a process that—when done right—could be profoundly educational for those involved.

Conclusion

In summary, although they understood the roles of organizer and educator slightly differently, Horton, Freire, and Baker agreed that in order for a group process to be educational, it must start with the knowledge of the people and empower them to realize their own knowledge and strength.

(For content and photo sources, please see the References page.)