After The Great Smog of 1952, change needed to be made, and quickly. Many factors contributed to the deadly pea-souper that fatal day, but through research, the Air Pollution Committee headed by Sir Hugh Beaver decided that unregulated burning of coal was a main ingredient that caused the health crisis. Initially, the Government resisted pressure to act, as they were more worried about the economic failure they faced. However, they eventually realized regulation was necessary. In 1956, the parliament passed the first recorded Clean Air Act. Although the bill came four years after the disaster, this was still seen as huge news for everybody living in the United Kingdom, as well as people living in other nations, whose governments followed suit.

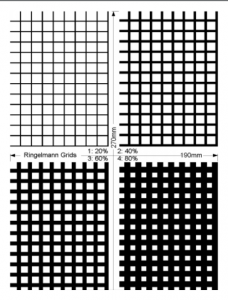

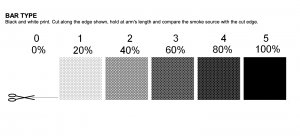

The legislative act, in no shape or form, was done sloppily. This was not a gander at political appeasement. The bill had every component to be incredibly effective, as it was thorough, detailed, and cleverly written. The law was heavily influenced by Ringlemann’s chart, which he created in 1888(14). The idea was that the darker the smoke, the more polluted the air becomes. Smoke darker than a specific shade of grey is classified as dark smoke seen on Model 1. This model is still used today on the UK’s official government website on preventing air pollution(13).

Ringlemann’s Chart (3).

Model 2: simplified version of Ringlemann’s Chart (3).

The Clean Air Act targets dark smoke, smoke from furnaces, grit and dust from furnaces, smoke control areas, smoke nuisances, Clean Air Council, and a few other miscellaneous provisions, as well as some exemptions from the law. The act prohibits all dark smoke from the chimneys of any building, be that residential areas or industrial plants. Not only were the citizens prohibited from installing new furnaces unless they complied in totality with the mandate, but they must also put efforts together in fixing pre-existing furnaces. Every boiler, furnace, or industrial plant attached to a building was only permitted to be built if it “operated continuously without emitting smoke when burning fuel”, citing that if one of these items were built without compliance to the law, the offender would be guilty of an offense and would have to pay a steep fine.

To enforce this rule and many more, local authorities were put in charge. Local authorities were told to induct tests and create task forces to penalize those who did not comply. The Act also made it clear that the proposed law was only a basement for air pollution restriction; if local authorities wanted to, they could advocate for stronger rules. They would need to say that they governed over a place that requires smoke control. Once the place was cited as a smoke control area, they would have full permission to add additional requirements to the law and any new provisions. The catch with this was, as not to give too much power to the local authorities, that people could appeal their verdict or their situation to the minister at any time to get it repealed. The Minister also has the ability to exempt any class of fireplace he deems. Churches, Charity buildings, and places of public good are also automatically exempt and will not be fined if they disobey, however royalty generally is not exempt. Even the queen can be reported for dark smoke if the local authorities notice it, a clause that was put in in order to maintain a level of equality for all.

There were many other parts of the act, such as water vessels in streams, rivers being restricted (unless they were military ships), quarries and mines were prohibited from burning their trash, and locomotives must use “any practical means there may be for minimizing the emission of smoke from the chimney on the engine” (18). All of this was incentivized by fines. If people or entities failed to comply, they would have to pay a fine that many could not afford, especially considering this was just after WWII and people were already down financially.

In an effort to make all of this happen, parliament offered to pay for a portion of the work done. The government offered to reimburse a generous 7/10ths of the money it cost to upgrade the furnaces so that they would produce less smoke. To avoid people using the government’s money for extravagant expenditure, they added a subsection of what that money would not pay for. This is possibly the most important part of this legislation. It is one thing to demand that people make changes to their smoke emission, but it is another to offer resources and money for people to actually do so. This is what made the law work. People were essentially given mini grants to make changes to their homes, and a lot of people actually did it! A real and substantial change was in the making.

The proposal was very clever in that it also had clauses stating that if they missed something specific, it could still be cited as a violation. The combination of general language and specific language glued the act together and made it an incredibly effective piece of legislation. After the act was made into a law, London continued to have deathly smogs up to the mid-1960s. This was in part because the law gave the citizens 7 years to fix their furnaces and anything else that released dark smoke into the sky. Before then, they would not be punished at all. This window of time provided a cushion to ease the citizens into this much more restrictive world. Many countries used the clean air act as a template to create some of their own substantial pollution laws. Though the law gradually made a positive impact on the environment, there were some faults in that. For example, the law failed to target big corporations as much as it should have. The law was later improved upon by the Clean Air Act in 1968, and then another one compiling all past air acts in 1993(3).