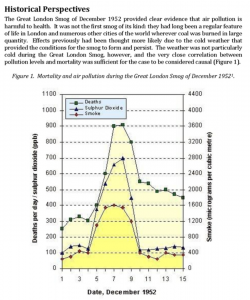

The long term effects of the Great London Smog are extensive. There are numerous health ramifications that have taken tolls on the survivors for the past 60 year since the Great Smog, and even more significant policies related to climate have been drafted. The aftermath of the disaster is profound. Though progress has been made in many departments concerning pollution policy, there are still many underlying issues that are ingrained beneath the surface that need to be fixed.

The aftermath of the disaster is profound. Though progress has been made in many departments concerning pollution policy, there are still many underlying issues that are ingrained beneath the surface that need to be fixed.

A real physical impact was made after the 1952 fog. In 1956, the first Clean Air Act was passed. Before the act approximately 275 ug/m3 ambient black smoke concentrations infused the air. After the Clean Air Act was implemented, concentrations steadily declined to about 100 ug/m3 in 1960 and followed a downward trend over the next 50 years (Brimblecombe, 2006). By 1966, concentrations were below 50 ug/m3 and by 1994 concentrations had decreased below 10 ug/m3. Everything changed radically in the next few decades. From 1960 to 1970, the use of coal as a fuel for industrial and domestic purposes declined due to smokeless zones that were emphasized in the act. In Manchester alone, the annual smoke concentration was reduced by a stifling 90%, from 1959-1984.  This is evidence that coal infused smoke from chimneys was drastically declining, which improved the air quality greatly. Though the dark smoke pollution decreased, other pollutions that were transparent continued to developed and pollute the atmosphere, causing more long term illness and wreaking havoc on our ecosystem.

This is evidence that coal infused smoke from chimneys was drastically declining, which improved the air quality greatly. Though the dark smoke pollution decreased, other pollutions that were transparent continued to developed and pollute the atmosphere, causing more long term illness and wreaking havoc on our ecosystem.

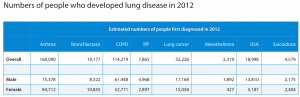

Though the death toll from bronchitis did go down a little, they are still incredibly significant and horrifying. In fact, in the last decades of the nineteenth century, the Registrar-General’s annual reports revealed that bronchitis had become England’s most common cause of death, killing between 50,000 and 70,000 people per annum.  Contemporary studies showed that the youth and elderly were most at risk from respiratory diseases, particularly in the working-class areas of industrial cities. Bronchitis is known to be directly linked to air pollution, so this is certainly a cause for alarm. Making matters worse, the British government declared just this year that circa 9,400 people died because of pollution. The gap between these numbers is astounding and proves that much like in the 1950s, the government is not stepping up and taking action. Instead, they are obscuring facts, endangering even more people(24).

Contemporary studies showed that the youth and elderly were most at risk from respiratory diseases, particularly in the working-class areas of industrial cities. Bronchitis is known to be directly linked to air pollution, so this is certainly a cause for alarm. Making matters worse, the British government declared just this year that circa 9,400 people died because of pollution. The gap between these numbers is astounding and proves that much like in the 1950s, the government is not stepping up and taking action. Instead, they are obscuring facts, endangering even more people(24).

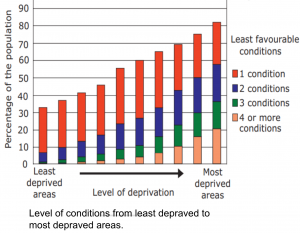

The differential effects are important to look at when considering why, now and back then, people are not stepping up and creating solutions. A large part of that is the working class are the people who suffer the most. Those who pollute the most do not bear the brunt of the consequences. This is environmental discrimination at its core. 662 of the sites coming within the Integrated Pollution Control (IPC) system in England and Wales are located in areas with household income of less than £15,000, whilst only 5 are in areas where average household income is above £30,000.  An ongoing problem with activism is that it is mostly done by people who have the time and energy to do so. Kissi-Deborah, the mother of the young girl who died due to pollution, talks about the difficulty of being an activist who is impoverished and of color.

An ongoing problem with activism is that it is mostly done by people who have the time and energy to do so. Kissi-Deborah, the mother of the young girl who died due to pollution, talks about the difficulty of being an activist who is impoverished and of color.

She says that black people in the UK are less affluent than other ethnic groups, and less likely to be able to spare time for meetings, protests or lobbying actions. Beyond racial inequality, environmental racism is an incredibly large and persistent issue in the UK. To even begin combating such issues, policies must be made that not only heavy-handedly deal with air pollution, but do so in a way that incorporates voices from the working class and minorities.

In order for this ideal to be feasible, more resolute leadership is required on the part of central government. Creating a national network of ‘clean air zones’ or ‘ultra-low emissions zones’ requires careful planning and the political will to implement such schemes. Delays in cleaning up urban air pollution cost an immense amount of lives of people who are already marginalized and discriminated against. Reports say that as of late smoke fumes are not the biggest issue to the pollution in London now. Most of the current pollution is that of which cannot be seen, which is admitted by vehicles as well as some factories. The government’s latest vague proposal was to make local authorities responsible for developing ‘creative solutions’ to reduce urban NO2 emissions, which is clearly not enough. The transition to cleaner automotive technologies will take time and money. Though the government needs to take immediate action, it is also the responsibility of the citizens. The public needs to play its part. More education is vital if the public are to grasp that invisible air pollution from vehicle exhausts is just as harmful today as the coal smoke that characterized industrial cities in the past. As was the case in 1956, motorists will need to accept some costs and make some sacrifices, to improve the quality of the air we breathe(24).