The London Smog of 1952 clearly shows the blurred line that exists between spectacle disasters and slow violence. It is true that in the catastrophic week, a giant spectacle was made. People died by the thousandfold, vision impairment was at its highest, and vehicular crashes occurred on every block. Yet somehow, it is still considered slow violence.

Of course, this begs the question: What is slow violence, and why does it actually matter whether it is classified as such?

Slow violence is dangerously subtle, occurring over a vast number of years until it becomes overtand plain for everyone to see. Slow violence is much less easy to recognize than a spectacle disaster. When there is a spectacle, one can be sure that there is a camera at the ready. In contrast, slow violence needs many more additional lenses to actually be understood and seen by the public, and this certainly applies to the Smog.

This was by far not the first smog that the people of London witnessed. For years before, yellow hues whirled in the backgrounds of pieces of art by famous painters. One example of this is seen in Monet’s work. Monet took steps to track the course of pollution in his paintings in the late 80s. By looking at his series of images, it is clear that the smoke began much earlier in history, though at the time it was not realized that the smog was pollution. His art gives modern scientists a lens into how ingrained the fog proble

m was in society; The hazardous fog was, in essence, normal. It is hard to separate London from its foggy skies, yet this smog is almost never equated with actual pollution. Even today, London still has a surplus of health issues because of air pollution. Behaving just like a slow disaster, it has taken forever for people to realize the disastrous effects pollution has on the lungs and other parts of the human body. The disaster is incredibly misrepresented, and because of that, nobody seems to know about it. However, a recent event took the attention of the news, which might actually change this(8).

m was in society; The hazardous fog was, in essence, normal. It is hard to separate London from its foggy skies, yet this smog is almost never equated with actual pollution. Even today, London still has a surplus of health issues because of air pollution. Behaving just like a slow disaster, it has taken forever for people to realize the disastrous effects pollution has on the lungs and other parts of the human body. The disaster is incredibly misrepresented, and because of that, nobody seems to know about it. However, a recent event took the attention of the news, which might actually change this(8).

Just days ago, for the first time ever recorded in history, a little girl was pronounced dead, withthe cause stated on her official death record as pollution. This is undoubtedly shocking and brought t he attention of many. 7 million people per year die from pollution globally, possibly more, and this little girl was the first one to actually be recognized. Every person who died in the 1952 fog should have had that same phrase stamped on their death certificate, but government figures were still apprehensive to admit that climate change and pollution have such a steep effect on people. In fact, it took over 60 years for one child to be recognized as a victim of London’s pollution failures. This is evidence that this disaster is slow violence. Despite the flash and attentiveness in the actual occurrence of the event, it was not truly recognized for years to come(9).

he attention of many. 7 million people per year die from pollution globally, possibly more, and this little girl was the first one to actually be recognized. Every person who died in the 1952 fog should have had that same phrase stamped on their death certificate, but government figures were still apprehensive to admit that climate change and pollution have such a steep effect on people. In fact, it took over 60 years for one child to be recognized as a victim of London’s pollution failures. This is evidence that this disaster is slow violence. Despite the flash and attentiveness in the actual occurrence of the event, it was not truly recognized for years to come(9).

As stated, this disaster did not only happen once. There were multiple occurrences where deadly fogs settled over a polluted city. This is a persistent issue, and it has real effects that are not as recognized as they should be.

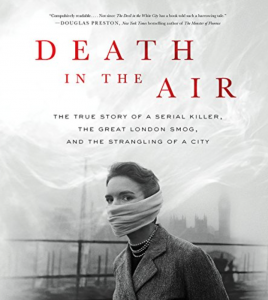

This example of a slow disaster is reminiscent to Rachel Carsons’s work, bringing the DDT disaster to the forethought of society’s minds. She wanted the DDT to be recognized as a real problem, and one of the ways she did this was by writing Silent Springs, a book the delves into environmental science. A strategy she implored was to combine different examples highlighting the horrendousness of the DDT into a singular narrative, so that it could be as flashy as a spectacle disaster. The London fog has a desperate need for a similar representation. It only has one real book, Dea th in the Air, by Kate Winkler Dawson, which looks further into the disaster. She writes about the Smog alongside the story of a serial killer, John Reginald Christie, who exploited the fog as a cloak for murder. At first, the author wanted the book to be solely about the smog, but she soon discovered that not enough work was published for her to be able to do so. This is because at the time of the fog, people were not as scared as they should have been, and failed to realize its effects until much later. Alongside the book, there are plenty of scientific articles published, as well as a few media reports who use the smog as a comparison to similar events in China. Slow violence is difficult to represent because it is so continual, and sometimes not obvious. Fog is not just something that happens in London; it is a part of the culture ingrained in society that presides in every nook and cranny within London’s people. The normalization of slow violence only makes everything worse. It leads to inaction, and perpetualization that everything is as it should be. For people to rise in arms and take action, further acknowledgment of the disaster must be made. Now, because of the little girl who died of pollution, we are the closest we have ever been to making real change.

th in the Air, by Kate Winkler Dawson, which looks further into the disaster. She writes about the Smog alongside the story of a serial killer, John Reginald Christie, who exploited the fog as a cloak for murder. At first, the author wanted the book to be solely about the smog, but she soon discovered that not enough work was published for her to be able to do so. This is because at the time of the fog, people were not as scared as they should have been, and failed to realize its effects until much later. Alongside the book, there are plenty of scientific articles published, as well as a few media reports who use the smog as a comparison to similar events in China. Slow violence is difficult to represent because it is so continual, and sometimes not obvious. Fog is not just something that happens in London; it is a part of the culture ingrained in society that presides in every nook and cranny within London’s people. The normalization of slow violence only makes everything worse. It leads to inaction, and perpetualization that everything is as it should be. For people to rise in arms and take action, further acknowledgment of the disaster must be made. Now, because of the little girl who died of pollution, we are the closest we have ever been to making real change.