The Dirty Thirties

The Dust Bowl refers to a period of drought, dust storms, crop failure, soil erosion, and poverty in the Southern Great Plains during the 1930s. Nicknamed the dirty thirties, these years also coincided with the post-World War I economic depression, which greatly compounded the effects of the crisis. The dust storms, also called black blizzards, were one of the most defining characteristics of the disaster; these storms could cover hundreds of miles and last for over ten hours (Hansen and Libecap 2020, 667). Because of these storms, the inhabitants of the Great Plains experienced a range of detrimental health effects from respiratory problems to heightened infant mortality rates (Worster 2004, 21). Many also lost their savings and fell into poverty as their wheat crops failed. Millions of Dust Bowlers migrated throughout the decade, some traveling as far as California, Oregon, and Washington in hopes of better job opportunities (Worster 2004, 39). In reality, these migrants, also called Okies, rarely escaped poverty by emigrating. Several effects of the Dust Bowl were mitigated in the late 1930s and early 1940s when Franklin D. Roosevelt passed over $525 million in federal drought relief (Worster 2004, 39). Eventually, the rains also returned to the Great Plains and the black blizzards subsided.

Cause and Effect

The Dust Bowl has several causes, some of which might be emphasized more than others depending on the narrative of the event and who is telling it. One of these causes is a series of federal land acts that encouraged westward migration to the Southern Great Plains throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These included the Homestead Act of 1862, which allowed settlers to claim 160 acres of land if they agreed to settle on it for five years, make land improvements, and pay a filing fee (Worster 2004, 82). The Kinkaid Act of 1904 and the Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 expanded this initial policy, and sped up the removal of Indigenous peoples, settlement by white families, and transformation of the landscape. When the economy during World War I caused a spike in the price of wheat, many farmers who had relocated to the Plains plowed their homesteads, replacing tall native grasses with cash crops like wheat and corn (Cook et al. 2009, p. 4998). A mindset of domination by man over nature pervaded, as did capitalistic incentives to exploit the land (Worster 2004, 4).

Some narratives of the Dust Bowl emphasize the role of new farming technologies like tractors, grain mills, and monocultures in facilitating unsustainable agricultural development. Other sources highlight overgrazing as the primary cause of soil erosion (McLeman et al. 2014, p. 422). During the 1920s, the Plains received ample rain irrigation, allowing farmers to reap enormous profits. But eventually wheat prices fell, and the rains stopped. All American states except for two experienced at least one drought year between 1930 and 1936, although drought was particularly severe in the Great Plains (Worster 2004, 11). Without the roots of native grasses, the moisture-lacking soil simply blew away, creating the dust storms. An estimated 10,000,000 acres in the southern Plains lost five inches of topsoil; the level of soil erosion that occurred during the Dust Bowl is unparalleled in U.S. history (Hansen and Libecap 2020, 666-8).

Heroes and Solutions

Just as numerous causes factored into the creation of the disaster, multiple resolutions and heroes emerge from disparate narratives of the Dust Bowl. Some argue that the people of the Plains, particularly those who remained and waited out the disaster, are the heroes of this story (Cronon 1992, 1348). When the drought ended, hardworking families were once again able to earn a living through agriculture despite the challenges of federal land policies. Other narratives emphasize the role of state intervention in resolving the disaster. Roosevelt passed several drought relief programs, including the Taylor Grazing Act and the Shelterbelt Project, which aided farmers and led to ecological restoration. Further, many Dust Bowlers benefited from federal New Deal programs which provided economic support to desperate Americans. In this way, the federal government sometimes emerges as the hero of disaster mitigation efforts.

An Unqualified Disaster

Although it is difficult to assess the true toll of the Dust Bowl, it’s clear that the crisis was, and continues to be, unparalleled in many ways. Historian Donald Worster offers a sobering assessment:

…the dust storms that swept across the southern plains in the 1930s created the most severe environmental catastrophe in the entire history of the white man on this continent. In no other instance was there greater or more sustained damage to the American land, and there have been few times when so much tragedy was visited on its inhabitants. Not even the Depression was more devastating, economically. And in ecological terms we have nothing in the nation’s past, nothing even in the polluted present, that compares. Suffice it to conclude here that in the decade of the 1930s the dust storms of the plains were an unqualified disaster. (Worster 2004,24)

Worster highlights multiple ways in which the Dust Bowl proved unprecedented. Not only was the ecological aspect of the disaster unparalleled, but so too was the economic damage, geographic reach, and societal tragedy. Although the sheer magnitude of the event is difficult to understand, it does ensure that the Dust Bowl remains one of the most prominent aspects of both U.S. history and collective memory—and for a good reason.

Parallels to Today

Several historians warn that we should apply the lessons of the Dust Bowl to the modern era. Hannah Holleman argues that we face what she calls a “New Global Dust Bowl” in which issues such as climate change, drought, food insecurity, freshwater scarcity, and land degradation are increasingly becoming worldwide threats (Holleman 2018, 27). Other historians have compared the magnitude of the Dust Bowl to modern-day disasters including Hurricane Katrina. In particular, researchers note similarities including the scale of food and water security issues, as well as human migration during these two disasters (Cook et al. 2009, 4998, McLeman et al. 2014, 417). Even economic disasters such as the 2008 financial crisis have generated a resurgence of interest in the Dust Bowl (McLeman et al. 2014, 27). Given the scale of the Dust Bowl, these comparisons should concern us; if we are indeed facing disasters of similar intensity as the Dust Bowl—or even a modern-day version—we would do well to apply the lessons learned from this disaster to those that are to come in the future.

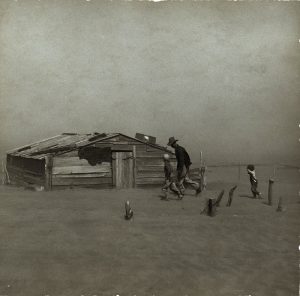

Image citations, in order of appearance:

- Arthur Rothstein, Farmer and sons in dust storm, 1936, photo, Oklahoma, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photos Division.

- Arthur Rothstein, A car is chased by a “black blizzard” in the Texas Panhandle, March 1936, photo, Texas Panhandle, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

- Dorothea Lange, Abandoned farm with windmill and farm equipment, June 1938, photo, Dalhart, Texas, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

- Arthur Rothstein, Two farmers harvesting grain with farm equipment, October 1939, photo, Costilla County, Colorado, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

- Dorothea Lange, Migrant family walking on road, pulling belongings in carts and wagons, June 1939, photo, Pittsburg County, Oklahoma, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

-

Russell Lee, Migrant man working on headlight of auto, July 1939, photo, Muskogee, Oklahoma, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.