The Collective Memory of the Dust Bowl

Much like the geography of the Dust Bowl, the collective memory of the disaster proves nebulous and elusive while simultaneously cohesive and defined. For example, inhabitants of the Great Plains tend to feel intimately connected to the event regardless of their exact place of residence (Porter and Finchum 2009, 212). Beyond the Great Plains, many Americans feel connected to the Dust Bowl through John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath or Dorothea Lange’s famous photos. And although Americans, regardless of geographic location, have embraced the Dust Bowl as an important part of U.S. history, the details of the event have become altered or obscured—both during and after the decade of drought. This page explores various aspects of the collective memory of the Dust Bowl, both throughout and following the disaster, in an attempt to explain why it is that so many feel a deep connection to this event. Through this exploration, it also becomes clear the ways in which the collective memory differs from historical events.

The Dust Bowl Happened Where You Live

In addition to written sources, collective memory also fails to consistently and accurately define the geography of the Dust Bowl: “Ask most people about the Dust Bowl and they can place it in the Middle West, though in the imagination it wanders widely, from the Rocky Mountains,  through the Great Plains, to Illinois and Indiana,” (Cunfer 2004). What accounts for these differences between our memory of the location of the disaster? To answer this question, researchers studied the vernacular geography of the Dust Bowl by interviewing nearly four hundred individuals living in the Great Plains (Porter and Finchum 2009, 2001). A striking trend emerged from these results. Individuals most commonly associated the Dust Bowl region with, “the location to which they have the strongest sense of attachment to place. In other words, the Dust Bowl happened where you live,” (Porter and Finchum 2009, 212). This finding, which is illustrated by the figure, reveals a strong connection between Great Plains inhabitants and their local history. The association between the disaster and the one’s home also likely reflects the widespread impacts of the crisis; families that experienced any number of events from dust storms to crop failure might all identify as Dust Bowlers. Overall, this research points to a collective memory of the Dust Bowl that is at once universal and fluid, at least within the Great Plains.

through the Great Plains, to Illinois and Indiana,” (Cunfer 2004). What accounts for these differences between our memory of the location of the disaster? To answer this question, researchers studied the vernacular geography of the Dust Bowl by interviewing nearly four hundred individuals living in the Great Plains (Porter and Finchum 2009, 2001). A striking trend emerged from these results. Individuals most commonly associated the Dust Bowl region with, “the location to which they have the strongest sense of attachment to place. In other words, the Dust Bowl happened where you live,” (Porter and Finchum 2009, 212). This finding, which is illustrated by the figure, reveals a strong connection between Great Plains inhabitants and their local history. The association between the disaster and the one’s home also likely reflects the widespread impacts of the crisis; families that experienced any number of events from dust storms to crop failure might all identify as Dust Bowlers. Overall, this research points to a collective memory of the Dust Bowl that is at once universal and fluid, at least within the Great Plains.

Okies vs. Exodusters: Misperceptions of Migrants

The stereotype of the Okie—used to describe destitute migrants—also captures an interesting tension in the collective memory of the Dust Bowl. Throughout the 1930s, millions of migrants traveled westward, often to California, in hope of finding jobs and better lives. Those living on the westcoast used the term Okie to refer to any migrant arriving from the east, even those from states other than Oklahoma. In reality, only about one-quarter of the migrants from the Great Plains hailed from Oklahoma (Worster 2004, 50). The Okie stereotype thus oversimplifies migration patterns and illustrates how this term shapes collective memory in a way that does not reflect historical accuracy.

The Okie stereotype also obscures the truth in another way. Not all of the migrants from Oklahoma were Dust Bowl refugees—who are also called exodusters. Most migrants fled not to escape dust storms, but rather to combat poverty and avoid loans. Of all the Oklahoma migrants, less than 5% came from the panhandle, the region with the most severe dust storms (Worster 2004, 61). The Okie stereotype was common throughout the thirties, but it also found its way into popular culture, media, and histories of the Dust Bowl. Because of this, the stereotype continues to infiltrate collective memory today, emphasizing a particular understanding of Dust Bowl migration that falls short of historical accuracy. Through the widespread use of the Okie stereotype, many more people were perceived as Dust Bowlers than was actually the case, which ultimately amplified the collective memory of the Dust Bowl.

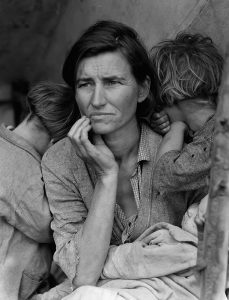

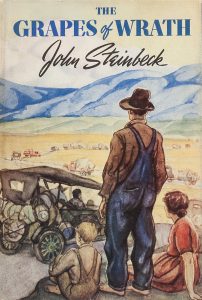

Above are two images that make part of the collective memory of the Dust Bowl. On the left is a still from the film The Grapes of Wrath showing the Joads, a migrant family from eastern Oklahoma. On the right is a portrait by Dorothea Lange of a woman with her children in California.

Popular Culture: The Grapes of Wrath

Perhaps the most compelling example of how the Okie stereotype manifested in popular culture is in John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. The novel portrays a migrant Oklahoman family from the eastern side of the state—around 400 miles away from the epicenter of the Dust Bowl. And yet the members of the Joad family are portrayed as victims of the Dust Bowl from the very first chapter:

Men and women huddled in their houses, and they tied handkerchiefs over their noses when they went out, and wore goggles to protect their eyes. When the night came again it was black night, for the stars could not pierce the dust to get down…the dust came in so thinly that it could not be seen in the air, and it settled like pollen on the chairs and tables, on the dishes. The people brushed it from their shoulders. Little lines of dust lay at the door sills…In the morning the dust hung like fog… (Steinbeck 2006, 3).

A widely read novel, The Grapes of Wrath likely contributed to the widespread confusion about the geography of the Dust Bowl much like the Okie stereotype. However, the book also undeniably connects a broad audience to the disaster. Over time, Steinbeck has significantly contributed to the preservation of the Dust Bowl within collective memory, even if his portrayal of the event is not entirely accurate.

Capturing the Zeitgeist of an Era

The Dust Bowl has occupied a prominent place in collective memory both during and after the event. Although certain aspects of the disaster were limited by geography or time, the Dust Bowl nonetheless clearly captures something powerful about the zeitgeist of the decade. To put it simply, people across the country felt connected to it, and continue to feel this way today. Perhaps we can attribute this to how widely the effects of the Dust Bowl—including drought, dust storms, and crop failure—were felt throughout the country. Even urban residents might have sympathized with the economic hardship and the disconnect to the land felt by the Dust Bowlers. In years since the disaster, generations continue to be captivated by the event, and the collective memory of the Dust Bowl remains at once grounded in a region and important on the national level.

Image credits in order of appearance:

- Porter, Jess C, and G Allen Finchum. 2009. “Redefining the Dust Bowl Region via Popular Perception and Geotechnology.” Great Plains Research 19 (2): 211.

- Allstar / Cinetext.

-

Dorothea Lange, Migrant Mother Series, 1936, photo, Nipomo, California, The Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

-

Steinbeck, John. 2006. The Grapes of Wrath. Penguin Classics. New York: Penguin Books.