A Wide-Reaching Documentary

The Plow that Broke the Plains, a government-sponsored 1936 documentary, offers a distinct narrative of the Dust Bowl and the New Deal. Written and directed by Pare Lorentz, the twenty-five-minute film features sparse narration, a dramatic musical score, and powerful imagery of both humans and machinery. Lorentz worked with a budget of $6000 provided by the New Deal Agency; his final product was produced by the Resettlement Administration. For the federal government, film production circumvented largely republican-controlled media platforms and thus provided a way to promote support of drought relief and New Deal policies.

Americans from many different geographic regions viewed the documentary—which some deem propaganda—as it aired in theaters across the country. For this reason, it proved a significant force in the production of a collective understanding of the Dust Bowl. It therefore merits the attention of modern scholars as they attempt to reckon with the competing perspectives on the 1930s. Ultimately, The Plow that Broke the Plains conjures an almost paradoxical narrative in which the same ecological and technological factors emerge as both the cause of, and the solution for, the Dust Bowl. According to the film, the primary difference between this cause and solution is that the latter requires state intervention in the form of drought relief and New Deal policies.

Origins of the Disaster

The vast majority of the film is used to set up an explanation of the origin of the Dust Bowl: a historic drought combined with the misuse of technological advancements. The opening scenes depict open grasslands devoid of people. As the images focus on the landscape, Thomas Chalmers narrates, “This is a record of land, of soil rather than people, a story of the Great Plains…A high, treeless continent without rivers, without streams. A country of high winds, and sun and of little rain.” Chalmers repeats fragments of this narration throughout the film, creating a refrain that emphasizes the ecological aspect of the disaster. Further, the film directly cites “the worst drought in history” as a primary cause of the Dust Bowl and Chalmers narrates, “The sun and winds wrote the most tragic chapter in American Agriculture.”

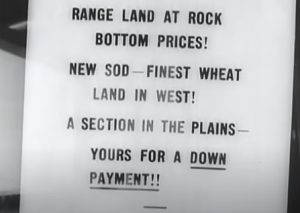

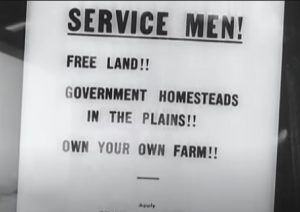

In addition to the natural origin of dust storms, the film also blames technology. Jarring visual shots frequently cut between farming technologies such as tractors and grain mills and military technologies including canons and ships. An intense soundtrack calls to mind military force, further cementing the connections between war, technology and the Plains. Lorentz accurately recognizes the consequences of wheat production and technology on the plains: “We put too many cattle and sheep in it. We granted homes in rangeland that never should have been plowed. We tore up grass. We invented new machinery making it possible for one man cheaply to plow thousands of acres.” This narration relies on the vague pronoun “we” and thus fails to acknowledge the role of the state in the formation of the disaster. The result is a perspective that rejects state responsibility and instead blames drought and technology as causes of the Dust Bowl. This representation is thus unidimensional and reflects a bias towards the state.

An Important Omission

Throughout the film, the state is considered not as another factor in the construction of the disaster, but rather as a lifeline for the impoverished people of the Plains. The section on wheat production during World War I illustrates this idea particularly well. Lorentz shows how World War I provided a strong impetus to plow the plains and produce a “golden harvest” of wheat. Chalmers narrates, “wheat will win the war,” while visual shots feature newspaper headlines boasting of cheap land for sale in the Great Plains. Ominous music and additional narration indicate that this mentality played a role in the creation of the Dust Bowl. However, neither the role of the state in the socio-political context of the war, nor the government’s settlement and land use policies are considered part of the cause of the disaster. Instead, the film places blame on technology itself in addition to the drought.

Disaster Resolution

In contrast, the film portrays state intervention as the primary resolution to the disaster in the closing minutes of the film. Chalmers narrates, “The federal government has worked strenuously during the past few years to restore the land. The Soil Conservation Service, the Forest Service, the CCC, and the Resettlement Administration are cooperating with the Department of Agriculture in working sixty-five land improvement projects in the plains.” By paring this narrative of New Deal intervention with images of destitute Dust Bowlers, the film ascribes the role of savior to the state. The more dire the portrayal of the situation, the more heroic state intervention becomes. Yet in a paradoxical twist, government solutions rely on modern technology and settlement—the very same factors that the film suggest created the Dust Bowl. These solutions include, “modern equipment, irrigation, good lands, electricity, sanitation, and schools. The resettlement administration is bringing these benefits to thousands who were left stranded and without hope.” The film suggests that modern technology and settlement of the plains ultimately led to the Dust Bowl, but also implies that these same factors, with the addition of state intervention, could remediate the crisis. In this way, the film offers a paradoxical story with a strong bias and one-sided argument.

The Plow that Broke the Plains perpetuates a particular narrative of the Dust Bowl: technologies like the plow led to the overexploitation of land, which, when compounded with a severe drought, led to a crisis. However, this assessment reflects a deep-seated bias towards federal relief efforts. It also minimizes the potential for government and corporate responsibility in the making of the disaster. Although Lorentz’s film evokes themes like capitalism and greed, the film stops short of any further analysis with regards to the creation of the disaster. In reality, federal land acts and land-use policies played a role in the creation of the Dust Bowl. Additionally, the film locates a contradictory solution to the disaster in drought relief and New Deal programs. Many of these programs celebrated modern technology and settlements—the very causes that underpin the crisis, even according to the film. Ultimately, the convoluted narrative of the Dust Bowl presented in the film illustrates the length to which the federal government sought to shape public opinion during the thirties.

All Images on this page are stills taken from Lorentz’s Documentary, The Plow that Broke the Plains: Lorentz, Pare. 1936. The Plow That Broke the Plains. United States Resettlement Administration.