The Jeju Island Uprising, also known as the April 3rd Uprising, resulted in the massacre of 25,000 to 30,000 Jeju islanders, the flight of 80,000-90,000 refugees, and the destruction of about 300 villages primarily between 1948 and 1953 (Task Force of Preparing Investigation Report of Jeju April 3 Incident [TFIR] 2014, 445, 455, 466). This disaster occurred at the height of anti-communist paranoia, the outbreak of the Korean War, and the U.S.’ establishment of a military government in South Korea. Its aftermath was defined by decades of political suppression and the government’s refusal of responsibility, compensation, or reconciliation.

March 1st Protests

The tensions that sparked the Jeju 4·3 incident first began forming in 1947, as ceremonies were planned for March 1st, a national holiday. The date celebrated one of the first public displays of resistance against Japanese rule and occupation and represented a significant source of national pride and the Korean independence movement. However, the United States Military Government in Korea attempted to limit the upcoming ceremonies and prohibited parades and demonstrations. As the day approached, it even declared emergency martial law to deter mass rallies; the U.S. feared these would devolve into protests against their temporary rule of South Korea (TFIR 2014, 123-124).

Regardless, nearly 30,000 Jeju islanders gathered at Jeju Buk Elementary school to “jointly perform a large-scale ceremony” (TFIR 2014, 128). Mainland police were sent in to keep order but the enormous scale of the crowd prevented them from breaking up the demonstration. Instead, they stood guard as community leaders reignited the spirit of the March 1st movement and called to reject the U.S.’ foreign influence over domestic affairs. Later, as the Jeju people dispersed and went back to their villages, a policeman’s horse, in turning around, accidentally kicked a six-year old child in the Gwandeokjeong Pavilion Square. The crowd went into an uproar and swarmed around the mounted policeman. As the outraged villagers chased him, armed mainland police “mistook their actions” for an attack and fired shots into the crowd, killing 6 people (TFIR 2014, 132-133).

Gwandeokjeong Pavilion Square: ground zero of the Jeju Uprising, digital image, accessed October 20, 2020, <http://thejejumassacre.com/gwandeokjeong/?ckattempt=1>.

General Strike

Over the next few weeks, public outrest broke out and the South Korean Labor Party, a left wing group, organized a massive general strike of 41,000 Jeju civilians in retaliation. Such a strike had never been done before in Korea: transportation companies, communications workers, factory workers, teachers, translators for the U.S., tax officials, and local policemen participated, threatening a shutdown of the entire island (TFIR 2014, 139-143). Even right-wing groups joined in on fundraising efforts for the victims’ families, who the islanders believed the mainland police had made no effort to apologize to.

Viewing this as a cause for concern, the US Military Government in Korea responded by simply pouring in more mainland policemen until they outnumbered the Jeju police, even though the strikers had made it clear their cause of anger was directed at the mainland forces, not the U.S.

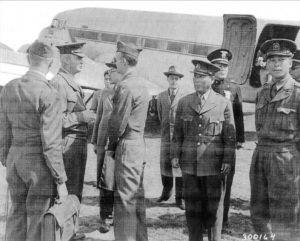

Leading members of the U.S. Military Government in Korea arrive at Jeju Airport, May 5, 1948, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: The U.S. National Archive and Records Administration.

Conflict on Jeju Island

Tensions accelerated and the U.S. began rounding up and arresting the leaders of the March 1st demonstration. To make matters worse, the U.S. also encouraged the right-wing enforcement of their crackdown and multiple right-wing youth groups began to assemble on the island (TFIR 2014, 177-179). These mainland police and right-wing forces arrested and tortured leaders of the general strike for months and engaged in acts of terrorism against suspected leftists. In response, Jeju islanders formed insurgent groups to protect themselves. Ironically enough, the ongoing persecution pushed many neutral islanders, who had no association with leftist ideologies, into supporting the few insurgents the U.S. was worried about.

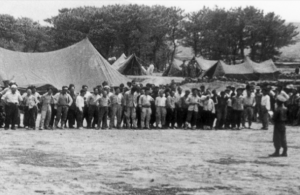

Inmates waiting to be interrogated, November 1948, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation) Source: The U.S. National Archive and Records Administration.

As these conflicts escalated, the Jeju Uprising officially began on April 3rd, 1948. 350 armed rebels attacked police stations and killed right-wing leaders in their homes (TFIR 2014, 132-133). In response, The U.S. military and President Syngman Rhee initiated an extremely brutal suppression of the rebellion by mobilizing the Korean Armed Forces, mainland policemen, and right-wing paramilitary groups (Yang 2018, 41-42). The US pushed for and authorized scorched earth operations, which meant destroying anything useful to the enemy.

Jeju Massacre

As a result, from 1948-1949, under the guise of this anti-guerilla campaign, the combined forces committed multiple war crimes. Scorched earth operations justified the systematic eradication of entire villages and innocent civilians. They indiscriminately rounded up and slaughtered islanders and burned their homes.

Jeju villagers forced to flee their villages, May 1948, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: The U.S. National Archive and Records Administration.

For example, in Gyorae-ri, these forces stormed Gyoraeo village at 5 a.m. on Nov 13, 1948. By daybreak, all of the village’s 100 households were in ashes. Survivors testified that, without notice, soldiers invaded houses and dragged out its residents to shoot, kill, and burn them. “All the victims were elderly people, children and teenagers.” Whether they were suspected of housing armed rebels or having communist sympathies, villagers like the 14-year old girl stabbed to death by a bayonet or the six-year old boy shot three times were mercilessly targeted (TFIR 2014, 470-471).

The prominent representative figures from legal, media, and educational circles were detained at the Jeju Agriculture School Camp, a setting that uncannily resembled the concentration camps the U.S. had fought against just three years before. These tent camps housed well-known figures and Jeju leaders in inhumane conditions. Most were tortured and eventually executed (TFIR 2014, 472-475).

Confined individuals at the Jeju Agriculture School, November 1948, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: The U.S. National Archive and Records Administration.

These efforts were brutally successful and by 1950, the few remaining rebels had fled to Mt. Hallasan. However, the Korean War broke out this year and the South Korean military ordered the preemptive targeting of possible lefitsts that could have North Korean ties. Hundreds more of innocent villagers were detained and executed via firing squad. Armed forces continued to target the guerillas hiding in the mountains until, in 1954, they were finally defeated, marking the end of the Jeju Uprising.