President Kim Dae-jung signing the Jeju 4·3 Special Law, January 11, 2000, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

The 2000 “Special Law for Investigation of Truth about the Jeju 4·3 Incident and Honoring Victims” established a committee to formally investigate the background, development, and aftermath of the Jeju Massacre (Task Force of Preparing Investigation Report of Jeju April 3 Incident [TFIR] 2014, 39, 49). This investigation collected and analyzed data before publishing The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report, a comprehensive collection of domestic data, international data, and recorded testimonies.

Data Collection and Comparison

The report’s damage report performs a particularly important role in assessing the overall impact of the Jeju Incident, an event that was covered up for decades by the South Korean government. This political cover-up likely obscured the facts behind the case, yet the committee still made an earnest attempt at truthfully investigating not just the casualties during the scorched-earth campaign, but also the killings of rebels’ families, innocent civilians through guilt-by-association, prisoners, and even the crimes committed by the guerillas.

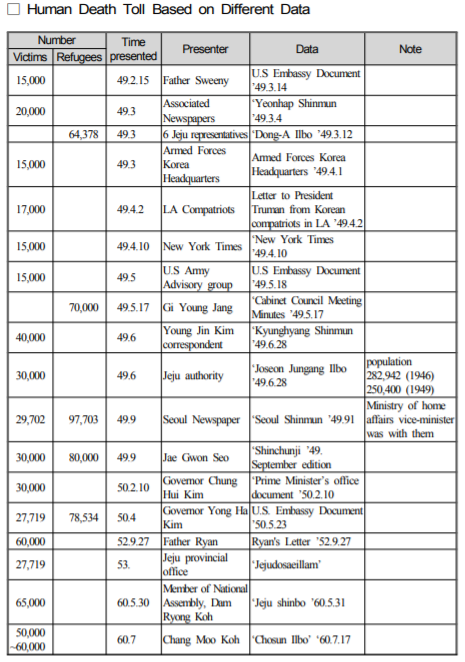

For instance, in specifically researching the number of innocents killed, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report collected data from multiple sources like official government data, informal historical sources, victims’ families’ reports, and reports to the committee itself, before analyzing the overall results to estimate a better prediction of the human death toll. The report compiled multiple tables showcasing these different numbers, categorized by qualifiers like age, source, time period, location, and gender.

“Newspapers, national assembly meeting reports, and U.S. Embassy records” (TFIR 2014, 451-453):

“The Human Death Toll Based on Different Data,” The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

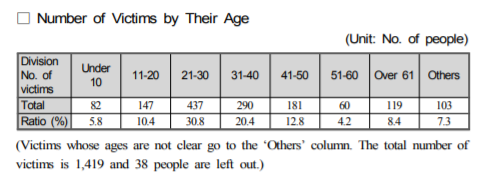

Victims’ families’ reports to the 1960 Investigation Committee for the Massacre of Citizens at the National Assembly (TFIR 2014, 456-457):

“Number of Victims by Their Age,” The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

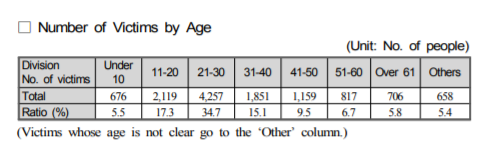

Victims’ families’ reports to the Jeju Provincial Council (TFIR 2014, 458):

“Number of Victims by Age,” The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

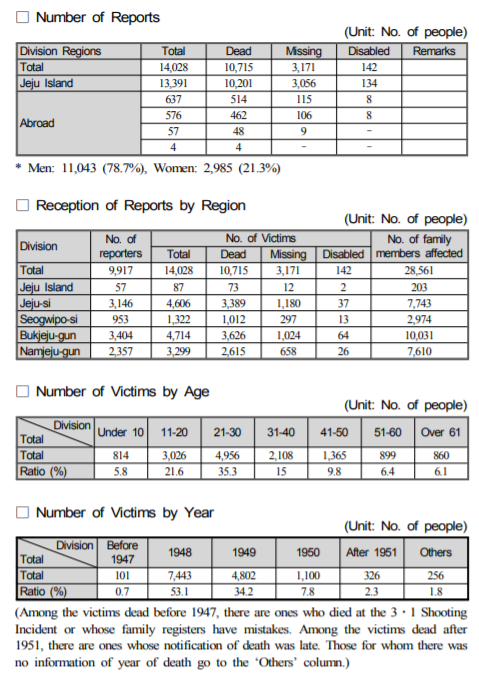

Findings of the Jeju 4·3 Incident Committee (TFIR 2014, 459-460):

“Number of Reports, Reception of Reports by Region, Number of Victims by Age, and Number of Victims by Year,” The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

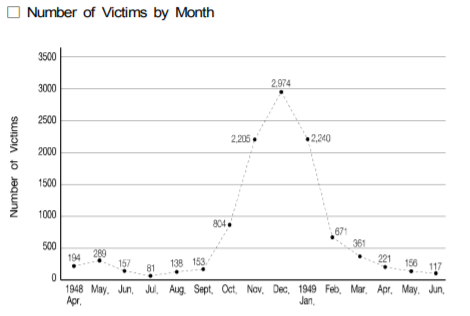

“Number of Victims by Month,” The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

The numbers discovered by the National Assembly, the Jeju Provincial Council, and the Jeju 4·3 Incident Committee showed that the victims under age 10 were all slightly around 6% of the total casualties while the victims over age 61 were all between 6 and 10% of the total casualties (TFIR 2014, 462). Consequently, the report, regardless of statistical variance, could establish that because most of the victims were killed by governmental forces and, based on the most conservative figures, at least 10% of the victim toll was under the age of 10 or over the age of 61, the “4.3 Incident was an infringement on human rights by the government authority” (TIFR 2014, 462-463). It didn’t have to rely on just the information that it researched, but could also compare it to historical evidence.

By clearly citing the sources that they received their data from and verifying or analyzing the truthfulness behind them, the report sought to clarify and present an objective evaluation of the Jeju 4·3 Incident. This comparative data analysis preemptively countered claims of bias or twisting the facts by accounting for the irregularities present in their different sources.

Testimonies

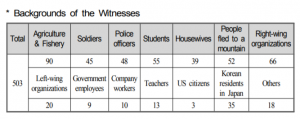

The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report also recorded testimonies to craft a better understanding of the massacre. The investigation committee created a list of potential witnesses by drawing upon those “mentioned in existing materials such as the damage and casualty report of the Jeju Provincial Council, newspapers, broadcast programs, and collections of testimony” and those recommended by institutes and organizations (TFIR 2014, 61). To ensure the truthfulness of these accounts and promote background diversity, the report even selected selected ex-members of the military operations and of the armed guerillas (TIFR 2014, 61). The committee then narrowed down this original list of 2,870 people to a final selection of 503 witnesses to be recorded by voice recorders and camcorders from July 2001 to October 2002 (TIFR 2014, 61). To ensure an accurate story was reported, the investigation analyzed these spoken testimonies by comparing them to others and ultimately organized them by location.

Final Witness List of the Jeju 4·3 Incident Committee (TFIR 2014, 61):

“Backgrounds of the Witnesses,” The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation).

One such testimony was provided by Kang Eung-mu under the report’s case of Haga-ri, or Haga Village. She explains that, because Haga-ri was located neither the beach nor upland, it was not forced to evacuate by South Korean soldiers, “allowing [its] residents to live normal lives even during the outbreak of the 4·3 Incident” (TFIR 2014, 479). Kang describes how soldiers raided her village of just 160 families at 1 a.m. on November 13, 1948, and dragged people, including her husband, out of their homes at random. After putting them in a yard, they “fired a machine gun at those people . . . [those] who were found alive were beheaded . . . they never looked liked soldiers but ‘human butchers’ to me” (TFIR 2014, 480). The report then establishes her testimony’s legitimacy and connects it to the incident writ large by analyzing how, in that same month, Wondong Village, Gyorae Village, Sinheung Village, Sangcheon Village, and Changcheon Village had all similarly suffered senseless massacre and arson (TFIR 2014, 480).

Yeonhwamot Pond, located in Haga-ri, July 25, 2020, digital image, <https://jejutourism.wordpress.com/2020/07/27/jeju-in-images-yeonhwamot-lotus-pond/>

This primary source is valuable because it does not simply submit individual testimonies. Rather, it actively organizes them and examines their relationships to shape a cohesive narrative of the incident. Though one could view Kang Eung-mu’s account, or the countless others cited, and attempt to explain the rationale for the soldiers’ killings as a mistake or isolated atrocity. However, when considered against the backdrop of an overlapping, interconnected quilt of spoken testimonies, the report presents an uncomfortable truth to the public and the government that is impossible to avoid or deny.