Massacres are characterized by the indiscriminate and unnecessary slaughter of defenseless people, generally occurring at the hands of political actors. They are manmade events that, like other disasters, generate human and material losses and disrupt normal conditions of everyday life; those issues hold heightened importance for massacres, as their very conditions require that humans directly sanction the mass killing of other humans. However, the Jeju Uprising also struggles to be neatly placed within categories of disasters. Rather than being a spectacle, it is also defined by the temporal challenges and representational biases that accompany slow violence (Nixon 2013, 11). Framing the swift and brutal extermination of innocent islanders as a spectacle ignores how the permeation of this slow violence significantly exacerbated this disaster’s consequences.

Temporality

To understand the disaster as a symptom rather than a singular instance, one must challenge the temporality underlying Jeju Island. Many accounts of the uprising assume that it occurred from 1948 to 1949, isolating the violence of the massacre to just two years and excluding the analysis of pre- and post-disaster considerations. Fixating on a beginning and end sanitizes the disaster because it provides a clean and convenient chronology to an otherwise complex tragedy, especially for responsible parties. In reality, neither the forces behind the killings nor the desires for rebellion spontaneously emerged in 1948. Left-wing and right-wing groups coexisted peacefully through self-governance on Jeju following World War 2, and tensions only grew as governmental suppression escalated (Park, 362-363); when civilians protested the mainland police murders in 1947, the U.S. and South Korean governments purposefully concentrated right-wing paramilitary groups and more police on the island to torture and terrorize suspected leftists, driving formerly neutral islanders to form and support insurgent groups (Park, 370.

The elderly, women, and children fleeing anti-guerilla operations by Commander Yoo Jae-heung, n.d., The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: Photo Album ‘History of the 2nd Regiment on Jeju Island.’

Similarly, the Jeju massacre did not end after 1948 nor did the forces that perpetrated anti-communism dissolve; the government targeted potential rebels well into 1956, massacred its civilians on at least seven more occasions following Jeju, and covered up the truth behind the disaster for another fifty years, arresting and interrogating any citizens that spoke up. Temporal displacement continued to perpetrate anti-communist violence while pushing back any real accountability for the killings through censorship. Strategies to cloud visibility distorted truth and contributed to the national amnesia that typically accompanies slow violence.

South Korea and American military officers posing, n.d., The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: General Kim Jeong-mu.

Representation

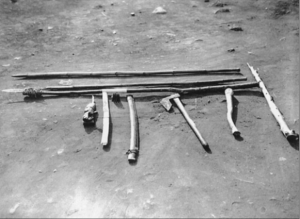

Jeju Island was also faced with representational biases that falsely portrayed the insurgents as a highly trained, dangerous force. In reality, the villagers “never had a sufficient number of weapons” (Park 2010, 360). Compared to the well-armed and well-funded South Korean and right-wing security groups, the rebels had access to a couple short rifles, pistols, grenades, and bamboo spears and axes (Task Force of Preparing Investigation Report of Jeju April 3 Incident [TFIR] 2014, 203). Still, government documents insisted that the guerillas were heavily armed with Japanese weapons like machine guns and cannons (TFIR 2014, 203). These lies served to further militarize the U.S. Military Government’s brutal response to the 4·3 Incident and the recommended scorched-earth policies.

Confiscated weapons such as bamboo spears and axes, May 1948, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: The US National Archive and Records Administration.

Furthermore, the Jeju insurgent forces never had more than 2,000 members fighting at any one point in time (Park 2010, 360). The massacres symbolized a gross overreaction to the small threat posed by the rebellion; these rebels were numerically outnumbered by the forces already present on the island in 1948, let alone the soldiers present just 4 years later. Representational challenges generated a narrative of an enormous, well-hidden enemy that concealed themselves in the villages and mountains of Jeju Island. Paranoia and normalization of this rhetoric led soldiers to target and kill civilians they believed to be aiding communist savages.

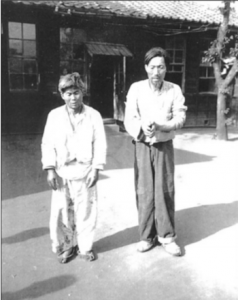

Arrested armed resistance members, May 1948, The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report (Revised Translation), Source: The US National Archive and Records Administration.

The case of Wondong Village starkly demonstrates the consequences of this narrative. A quiet neighborhood with a “low number of youth likely to join the rebels,” the police should have had no reason to view it as a major threat. Still, this logic didn’t stop soldiers from searching the village and, upon finding no rebels, mercilessly killing “every dweller in sight regardless of age or gender” (TFIR 2014, 481). After killing dozens of these inhabitants, a U.S. report revealed that “115 rebels were killed in . . . coordinations of 937-1133” (TFIR 2014, 482). The Jeju 4·3 Incident Investigation Report later located these coordinates and found that they pointed “exactly to Wondong”; these falsely construed documents rewrote the massacre of “toddlers aged four to elders in their 60s” into a nameless mob successfully dealt with, washing away the atrocities committed there (TFIR 2014, 482).

Throughout the Jeju Uprising, how many other ‘Wondong Villages’ did governmental reports attempt to erase from history?

How many are now truly forgotten?

Thus, by falsely depicting villagers angry at their loss of independence as a dangerous force to be eliminated, the U.S. and South Korean government was able to construct an imaginative security threat to their national interests and promote merciless violence against innocent people.