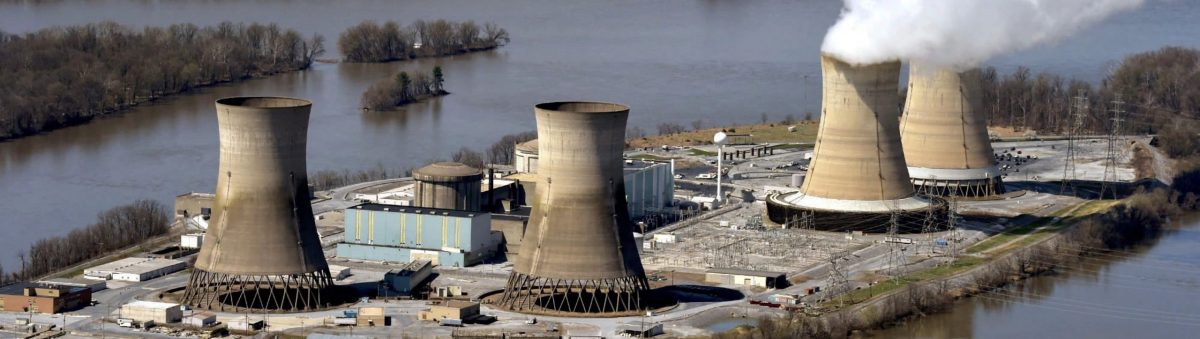

In the decades after World War II, the nuclear industry shared the same economic growth and era of good will enjoyed by the United States at large. So when energy company Metropolitan Edison announced in 1966 its plans to build two nuclear reactors on Three Mile Island near Middletown, Pennsylvania, the news was met with general excitement for the economic opportunities the plant might bring (Zaretsky 2018, 62). Dauphin County, where the plant would be located, was home to a predominately white, working-class population, and the region was facing economic pressure as deindustrialization trends harmed local steelworkers (Ibid.). Construction on the plant began two years after Met Ed’s announcement, with the second reactor, TMI-2, going online in February 1978.

Disaster Strikes

One year and one month after first producing electricity for the state of Pennsylvania, TMI-2 had a problem. At 3:58 am on Wednesday, March 28, 1979, moisture from leaky seal in the reactor’s water cooling system caused two water cooling pumps to shut down. The reactor’s steam generators began to overheat without the water necessary to keep them cool, and the plant’s nuclear reactor began to overheat with it. The pressure in the reactor core increased with the temperature, prompting a pressure release valve to automatically open.

Had the release valve closed when the system pressure returned to a normal level, the effects of the core’s rising temperature might not have been as extreme. The valve, however, became stuck open – and even worse, the valve’s indicator light failed, erroneously informing the plant operators that the valve had closed. The effects of this malfunction were twofold: cooling water continued to escape from the reactor in the form of steam, and the plant’s staff failed to realize that the reactor was experiencing a loss-of-coolant accident and did not take the appropriate measures to prevent it.

Instead, the plant workers turned off the cooling system in an attempt uncover the reactor core, assuming the core had maintained an appropriate temperature. As a result, water continued to escape the system, with some radioactive steam finding a way out of the plant through its air conditioning system. The pressure and water level in the reactor continued to decrease, and the core overheated, resulting in the reactor’s partial meltdown. The federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) was notified of the accident at 7:00 am, three hours after it began. Two hours after that, Americans around the country tuned into their morning news and beheld a frightening reality. The nuclear power plant at Three Mile Island was failing.

(description in this section drawn from: NRC Backgrounder; NYT 1979; Scharre 2016, 26-27)

Aftermath

In the hours and days following the accident at TMI-2, chaos ruled. Met Ed, eager to project optimism about the crisis, released few details from the early hours of the disaster to either the NRC or to the public. Instead, outside experts were left to speculate about the true scope of the accident, and their conflicting predictions did little to inspire public confidence. Federal officials and news media alike frantically sought information about the crisis, but little was forthcoming as local officials and the public were left uncertain of how to respond.

Unwilling to do nothing and be proven wrong later, Pennsylvania governor Dick Thornburgh took tentative steps to protect the Middletown community. The governor issued a stay-at-home order for the ten mile radius surrounding the plant, while simultaneously advising pregnant women and children four years old and younger to evacuate in a five mile radius. Confused by the governor’s advice and fearful of the worst, many area residents began to flee on their own initiative, distrustful of the information they were receiving from Met Ed.

On Friday, two days after the accident, public alarm reached a peak after a report surfaced that a hydrogen bubble in the failed reactor might burst, causing a nuclear meltdown of drastic proportions. Just as soon as the panic struck, however, it receded, with Met Ed scientists confirming a false alarm that Sunday. The bubble was gone the next day.

Soon after, experts would confirm that the compromised nuclear reactor did not pose a serious danger to the local Pennsylvanians. Workers at the plant began taking steps toward a “cold shutdown,” laboring over the coming months and years to clean up the nuclear mess at TMI-2. No deaths were recorded, and residents slowly resumed their normal activities. While physically unharmed, the region remained scarred from the hysteria and misinformation that defined the initial aftermath of the disaster.

(aside from the portion directly referenced, all description in this section from NYT 1979)

Regional Effects

As multiple scientists would confirm in the years after the disaster, the health effects of TMI-2’s meltdown were minimal at worst. Several independent studies indicated that the radiation exposure borne by those who lived near the reactor was less than that of a chest x-ray, and no adverse health effects were discovered (NRC Backgrounder). Scholarship in years since these studies have cast some doubt on their objectivity, with one more contemporary researcher alleging bias in the scientists who studied the disaster radiation (Environmental Health Perspectives 1997, 22). Significant adverse effects from radiation poisoning, however, have never been documented.

While the radiation exposure the crisis wrought proved inconsequential, the accident was not harmless. The lives of the mostly rural working class community around TMI were subjected to extraordinary upheaval in the days after the disaster, with psychiatrists finding severe demoralization and mental health problems in local residents (Nelkin 1981, 135). While TMI’s nuclear scare may have been a more distant problem for government agencies and Met Ed, its effects were directly experienced by the economically disadvantaged locals, who were forced into difficult decisions between working and fleeing, sustenance and safety.

Remembering TMI

The TMI-2 reactor remained permanently shut down after 1979. The reactor’s waste was shipped offsite and disposed of; cleanup at the location ended in 1993 (NRC Backgrounder). TMI-1 continued to operate as a nuclear reactor until it was shut down on September 20, 2019 (NYT 2019). The name Three Mile Island, however, will always carry with it the weight of the chaotic accident at the plant in 1979. The incident is remembered for its dramatic effect on cultural sentiment around nuclear energy, as well as the impetus it provided for increased government regulation of the industry.

With the lessons of Three Mile Island more than 40 years old, 98 nuclear power plants continue to operate in the United States, providing roughly 20% of the nation’s electricity output (NYT 2019). Nuclear power remains vivid in the national conversation both for its dangers – as evidenced by a 2011 disaster at a Fukushima plant – and for the immense promise it carries as a source of clean energy as the world continues to warm.