Nuclear technology first entered the world in a shroud of secrecy and uncertainty. Impetus for the creation of the first atomic bomb was as much scientific as it was the result of rampant speculation that the Nazis were developing atomic capability of their own. The United States’ first major nuclear effort, the Manhattan project, was likewise highly confidential. And when the Cold War fomented public apprehension about nuclear technology on a national scale, the public fantasy around nuclear energy grew even more lurid (Wills 2006, 120).

The secrecy surrounding “nuclear energy” – whatever that was – ensured that media portrayals of the technology would have an outsize ability to frame public attitudes and expectations around it (Wills 2006, 109). When the public raced to grasp the ramifications of the TMI disaster in its messy, ambiguous aftermath, then, the media they consumed had a large effect on their understanding of the disaster.

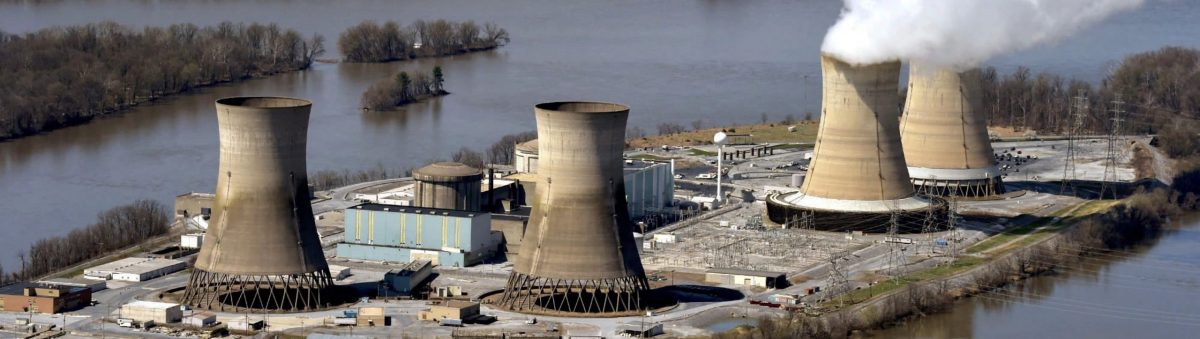

A Blockbuster Coincidence

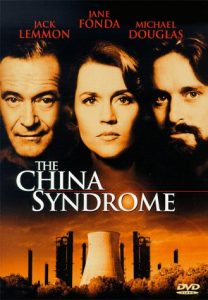

A mere twelve days before the TMI-2 reactor suffered a partial meltdown, Hollywood thriller The China Syndrome landed in theaters nationwide. The film, starring Jane Fonda and Michael Douglas, portrays a television reporter’s intrepid investigation of a fictional nuclear power plant in California. Everything that can go wrong at the plant does, and Fonda’s character is left to witness a harrowing nuclear disaster in the making. Producers of the highly dramatized movie drew on documented instances of corruption and misfortune at real-life US nuclear facilities, and the film’s portrayal of these facilities was not kind – energy utilities were framed as mischievous tricksters that valued profit over safety, and nuclear employees were made out to be grossly negligent in maintaining order at the California plant. Federal authorities, too, were cast in an unflattering light, depicted as bumbling and inept in responding to nuclear crisis (Wills 2006, 111-12).

The China Syndrome was already poised to take advantage of growing public distrust of nuclear energy in the 70s, but when TMI-2 melted down mere days after the movie’s release, the film enjoyed the brightest spotlight imaginable. As much of the American public attempted to make sense of the accident, the version of nuclear power the movie portrayed proved vivid in the collective imagination. Those uncertain of how to respond to the TMI accident looked to The China Syndrome as a frame of reference for unfamiliar technology (Wills 2006, 114).

“This Whole F*cking Thing was Produced by Jane Fonda!”

The national news media was not immune to the allure of The China Syndrome. The movie provided accessible and palatable information to a press corps no likelier to possess nuclear expertise than the American public writ large. Reporters were known to attend showings of the film near Middletown, touting it as their “inside view” of the disaster (Wills 2006, 116).

It should come as no surprise, then, that the media tended to conflate Hollywood with reality. Time and Newsweek both drew explicit parallels to The China Syndrome in their reporting, and media outlets did not successfully distinguish the response of the movie’s fictional energy company, California Gas and Electric, from that of Met Ed (Mazur 1984, 60). The media reporting on the accident transposed much of CGE’s malice and manipulation onto Met Ed – and while Met Ed did have some issues with transparency and availability, its shortcomings were nowhere near Hollywood’s portrayal (Wills 2006, 116). In a similar manner, federal authorities like the NRC struggled to shed the bumbling and inept image the media had saddled them with (Wills 2006, 117).

All too easily, public reactions to the accident veered toward alarmism and panic as The China Syndrome set public expectations for the disaster’s mitigation efforts. The film proved so popular that an executive at the Atomic Industrial Forum, while referring to the drama surrounding TMI, quipped that “this whole f*cking thing was produced by Jane Fonda!” (Wills 2006, 117)

The News Media Struggles

The missteps taken by the national news media did not end with its overwrought focus on The China Syndrome. The media’s responsibility was immense: coverage of the TMI accident consumed nearly 40% of evening news during the first week as the public frantically searched for accurate information about the disaster (Mazur 1984, 45). And in some key ways, the media failed to meet its responsibility.

Much of the media’s struggles were outside of its own control. The radioactive TMI reactor was necessarily shielded from public access, creating a crisis of visibility in which the entire nation grew more desperate for information about something they could not see (Zaretsky 2018, 72). Moreover, the convoluted and highly technical nature of nuclear energy, combined with initial uncertainty among experts about the seriousness of the disaster, came into direct conflict with the pressure for immediate reporting (Nelkin 1981, 139). Journalists with no prior knowledge of nuclear power were suddenly tasked with making it digestible for an entire nation.

A harrowing example of the dangers of media hype came with the hydrogen bubble scare, which first emerged on the Friday after the initial meltdown. An employee at the NRC phoned the Associated Press with a dire warning: the bubble, he said, might soon explode. The AP promptly published a story, only for experts to confirm two days later that the bubble presented no danger to the surrounding area. The news media got it wrong, but it’s worth noting that the erroneous information originated with the NRC. This proved to be a pattern, as journalists gave generally accurate reports, with most factual errors traceable to government and business sources of information (Mazur 1984, 60).

Imprint on the Public Consciousness

The nuclear accident at Three Mile Island proved highly consequential for the way it shifted public impressions of nuclear energy, and much of this shift is attributable to the way the media constructed the technology for Americans in the aftermath of the disaster. Between The China Syndrome and the relative accessibility of the Middletown, PA area to journalists, TMI happened at the right place and time to become the center of public attention (Mazur 1984, 48).

The national attitude toward nuclear power was directly affected by the quantity of media coverage. Public opposition to controversial technology generally correlates with increased journalistic attention to that technology, and TMI was no exception (Mazur 1984, 64). Representative Morris Udall (D-AZ), chairman of a House subcommittee on energy observed later that the “incredibly optimistic” view toward nuclear technology of the 50s and 60s had been dramatically shaken by events at TMI (Carter 1979, 155). Indeed, the combination of The China Syndrome and TMI, a mere 12 days apart, fostered public dialogue about nuclear energy, which in turn drove a surge in political activism (Wills 2006, 118).

As the founder of advocacy group People Against Nuclear Energy proclaimed after the accident, “we’ve borne our share of the nuclear experiment” (Walsh 1981, 9). The American public had revealed the secrets of nuclear energy, and decided that the technology was better suited for works of fiction.