In his two performances of The Failure of Defense, Dai Guangyu uses material, composition and performance to illustrate contemporary issues such as globalization, westernization, destruction of culture, (any thing more specific so those phrases would not sound general) etc. as they relate differently to China and the United states.

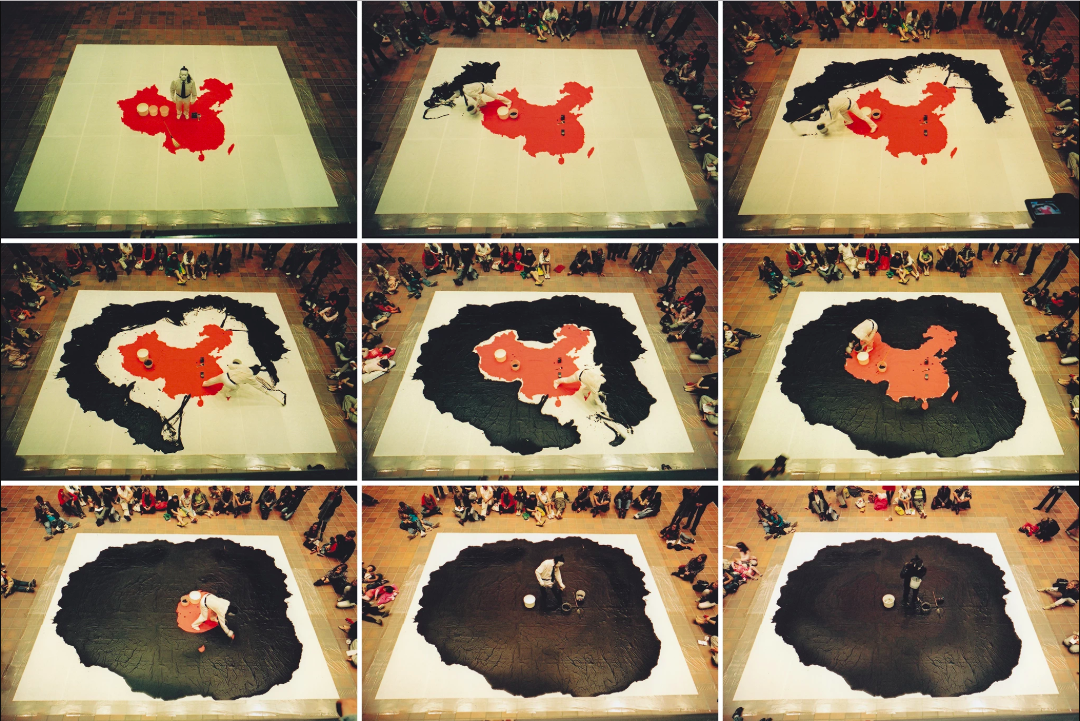

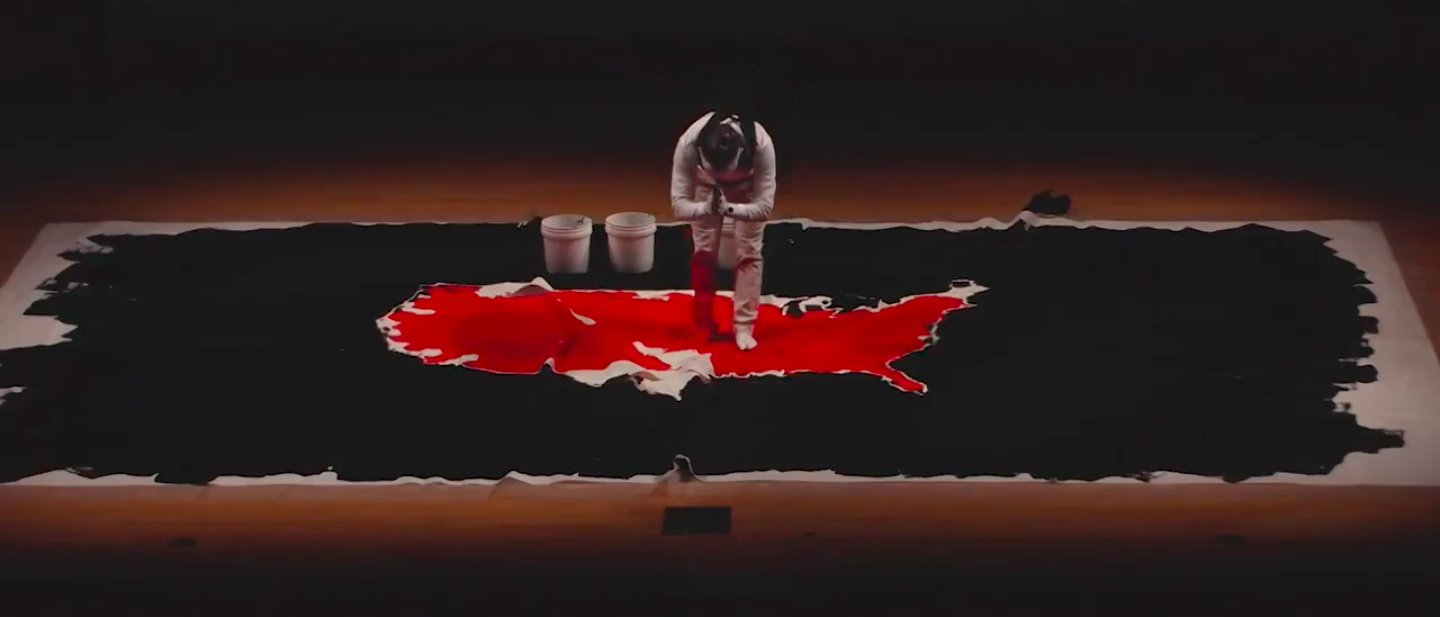

Guangyu’s use of the traditional ink uses the historical significance of the material to give cultural significance to the symbolism of the ink in representing themes such as globalization and westernization.(further clarify the connection between ink and globalization) Trained in classical calligraphy as a child, Guangyu’s use of ink is rooted in tradition both nationally and personally. In both performances of The Failure of Defense, the ink is used as the primary feature of his performance. However, what is unique from his other works, is that the ink, while still having traditional significance, does not represent Chinese traditional culture, but instead invites the viewer to interpret the symbolism of the black ink. The black ink is commonly interpreted to represent themes such as globalization, westernization, modernization, economic power and military power. In both pieces, the red ink seems to represent the culture of the country in each respective piece. The contrast between the two ink colors represents the contrast between traditional culture (red) and the other themes like globalization (black). Hence, the traditional material of ink is manipulated in this work to represent the dichotomy between tradition and threats to tradition and culture. (stay with the title as well as the central thesis of “failure of defense” in terms of color contrast between red and black?)

Dai Guangyu

The composition difference between the original piece in 2007 (pictured above) and the rendition performed in 2017 (picture and link below) illustrate the different experiences of the US and China in respect their contemporary cultural (ten years apart, is it consideration of US-China relations?the analysis could be further supported with US-China relations). In the 2007 rendition, the black ink can be seen slowly overtaking the red shape of China, until the entire canvas is black and Guangyu even paints himself. (performance art is supposed to take the body as the site/medium) Common interpretations of this piece are that the black ink represents western culture and globalization, and how China’s culture has been erased by the nation’s transformation into a global power by failing to defend against the black ink. By the end of the piece, the red shape of China has been completely covered by ink, representing the dominance of globalization/westernization compared to China’s preexisting culture and traditions.

In the 2017 rendition, the black ink forms the outline of the United states while red ink drips from Guangyu’s leg to fill in the outline of the US. The contrast between the final compositions of the two pieces is that in one, China is covered by the ink and in the other, the US remains untouched by the black ink. One interpretation of this contrast is that globalization and westernization define the US and US culture, whereas they erase Chinese culture. If the black ink is seen as representing economic power, one could interpret that China has allowed the pursuit of economic power to prevail over the maintenance of traditional culture. In the US, however, the development of US culture has evolved in parallel with the pursuit of economic power, instead of one dominating over the other. The second rendition, however, can also be interpreted as an individual piece, not as a diad with the original work. In light of the 2016 election, the 2017 Failure of Defense could represent the US failure to defend against an extreme candidate and the social movements that led to his election. Overall, the compositions of the two pieces can be compared in order to analyze the contrast between the two pieces and their respective symbolism, but Guangyu can also adapt the original piece in order to speak to contemporary issues such as recent elections. (in consideration of China as the rising power and competent with US, the color and composition transition could make much more sense)

Dai Guangyu

The performative differences between the two pieces represents the different experience of globalization (and the other themes) in China compared to the US. There are two main differences between the performance in 2007 and 2017: the first is that in 2007, China is painted in red prior to the start of the performance and in 2017 the US gets filled in during the piece. A literal interpretation of this difference is that China is a much older country, and existed with its culture and traditions long before the industrial revolution and globalization. The US, on the other hand, was established as a country at the beginning of this period of global transformation. As a result, US culture developed in parallel with globalization rather than being erased. This same interpretation applies with the other themes such as westernization, modernization and economic power. The second difference is that Dai Guangyu does not paint himself in 2017 as he does in 2007. As a Chinese man, Duangyu uses the significance of painting himself to humanize the symbolism of the work. As an audience member, there is much more empathy for a human being painted by the black ink and all that it represents. Therefore, Guangyu capitalizes on this emotional response to emphasize the human experience of culture being erased in the face of globalization. Guangyu uses enhance the experience of the viewer and further emphasize the symbolism, enhancing his overall goal to translate the different experiences of the US and China in the wake of globalization.

Overall, the two pieces are complex in their symbolism, lending themselves to many interpretations. Guangyu’s choice of material, composition and performance all complement one another in their symbolism and together create this complexity. The openendedness of the work lends itself to sparking conversation and thought regarding all that the piece can represent. This capacity for sparking conversation and contemplation is seemingly the goal of the work and is well executed in both renditions, demonstrating the timelessness of the work as it can continue to address contemporary issues.