Zhang Dali is one of the most famous artists who did graffiti art in the streets of Beijing. Between the years 1995 and 1999, he did a series of graffiti of the profile of a bald head on buildings waiting to be destroyed in the urbanization effort by the Chinese government. In his series “Demolition and Dialogue,” Zhang Dali “hoped to engage the city in a “dialogue” with himself” by putting his likeness throughout the city. However, as Wu Hung remarks, from simply observing the nearly four hundred photos he had access to, “one gains less knowledge of Beijing than of the artist’s contested relationship with the city” (Wu, 2000).

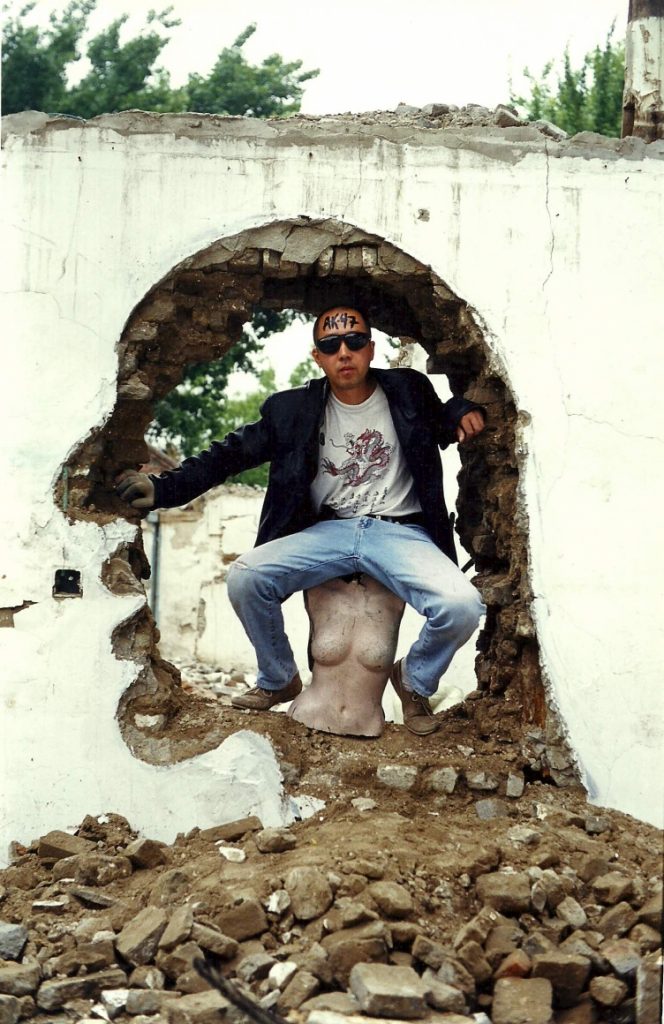

This picture stuck especially because it not only contains the signature outline of the artist, but also himself as part of the art. Clearly, Zhang is trying to make a statement with his own presence, but it is unclear to me exactly what he is trying to say. There are a few features that singles this photo out from the other few hundred in the same series: the artist himself and the female body statue he is sitting on. (are you going to develop this idea?)

As Zhang mentioned to Wu, putting “a condensation of my own likeness as an individual” allows him “to communicate with the city.” Therefore, the bald head serves as a representation of the artist. Hence, it would be redundant if Zhang had intended for his own presence to simply place himself in the artwork. Therefore, his choice to be in the artwork himself must symbolize something other than his own identity. In my opinion, Zhang Dali himself in the piece represent the thoughts and opinions of the artist, being inside his representative head.

Instead of scribing his signature slogan of “AK-47” on the wall, Zhang writes it on his forehead. This slogan is usually written somewhere close to the graffiti image on the wall, sometimes completely inside the head. Because images of guns are prohibited in China, the slogan, representing a powerful assault rifle originated from the Soviet Union, symbolizes military power and threat. If we replace the strain of words with the actual image of the weapon, the image becomes a gun pointing at the artist’s head. In this case, Zhang chose to put it on his forehead instead of that of his likeness, maybe to signify that the metaphoric gun is pointing at and threatening his thought, or who he really is.

All the while, he is sitting on a statue of a female body, in a gesture that can only be interpreted as his dominance over the female body. Whether or not Zhang is championing a specific gender power dynamic is unclear, but it is sure that this is his way of engaging the city into a dialogue about the topic. As Wu writes, “the question these photographs evoke is not so much about the content or purpose of dialogue, but whether the artist’s desire to communicate with the city can actually be realized—whether the city is willing or ready to be engaged in a forced interaction.”

Wu Hung, Wu. “Zhang Dali’s Dialogue: Conversation with a City.” Public Culture 12, no. 3 (January 2000): 749–68. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-12-3-749.