Xu Xiaoyan is an eco-feminsit, who specializes in oil paintings of landscapes. These landscapes typically show the earth being destroyed or polluted by the urbanization of China. Through her eco-feminist lens, the goal of these paintings are to highlight how urbanization is damaging mother nature, which she believes is symbolic of feminity and female identity. In these paintings, the way in which she exemplifies how urbanization is harming the earth and also female identity is through her use of the female anatomy within the paintings and her use of color.

The use of female anatomy within the picture allows the viewer to clearly see the connection between the earth and femininity thus highlighting how man made urbanization is destroying it. In her painting Body of the Earth, the focal point of the picture is “a conspicious vaginal shaped hole” (156). This hole is being invaded and destroyed by the debris left behind from construction. This symbolizes how man made structures and Chinese urbanization are encroaching and destroying the female identity within China, as well as harming the earth. The action of the hole being invaded and destroyed shows how urbanization is harming the environment as well as invading upon female progress and masking female identity.(try not to repeat what you have already expressed)

In another one of her paintings in the foreground there is a river that is heavily polluted and in the background there are skyscrapers. Again, the river is painted in a way to resemble the female anatomy. The fact that this river is polluted conveys the same message as the last painting, that female identity is being harmed, invaded, and suppressed through these man made structures, which the skyscrapers in the background represent. (make a connection between mother nature and female body. in so doing, there would be more comments that could be made)

Body of Earth

In these two paintings she also uses color to portray the destruction of the earth and female identity. In the painting Body of Earth, she contrast the colors in the foreground and background to highlight this. In the foreground, where the hole is being invaded and polluted, she uses very harsh, dark colors. These colors are dark reds and browns to symbolize blood and destruction of the earth and the female. She wants the viewers to see that the construction from urbanization is physically harming the earth and the female. While in the back, where the landscape is untouched, she uses softer colors like greens and yellows, that symbolize the nurturing qualities of the earth and femininity. She uses these soft colors to highlight the beauty and femininity of the untouched landscape. Through these soft colors she tries to convey a feeling of safety and attractiveness to this version of the earth and compel the viewer to try and preserve the earth and femininity rather than destroy it.

In the second painting, she paints the foreground, which is the polluted river, in very dark harsh colors again like browns and blues. She does this to highlight how bad the pollution is and how urbanization has stripped mother nature of its femine and nurturing qualities. In the background, which is the skyscraper, she paints the buildings and sky with light and dark grays. She uses these greys in order to devalue the skyscrapers and convey the gloomy and destructiveness that urbanization causes to the earth. She does not want to glorify this urbanization in any way so she chose to paint them in the greys to make urbanization seem negative.

Throughout Xu Xiaoyan’s artworks she tries to convey to the viewer that the current state of Urbanization in China is harmful to mother nature and female identity. Being a eco-feminist causes her to view the enviroment and feminity as connected and symbolic of one another. Therefore, in her paintings she tries to represent that ideology artistically through creating pieces that have elements that resemble the female anatomy. After, she has visually established the connection between the environment and femininity in her painting, she then highlights the destruction of the two that urbanization is causing. She also uses the colors within the painting to highlight this pollution and destruction of the earth and femininity to drive home this message to the viewer.

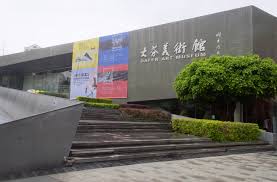

The Village has also transformed its identity from a local producer to a global producer of art work. This is highlighted through the villages Main Street, where the artworks are sold. All throughout the street there are many shops and artist selling thousands of pieces of art. In the past many local Chinese and Chinese business vendors would come to Dafen to buy these works. However, now thousands of tourists and businesses from various parts of the globe flock to Dafen to buy the artwork. They still sell reduplicated works, but the main focus now is on original artwork produced by the young local villagers. This gives the villagers and the village a new incentive to embrace art as a medium to expose their talent and identity worldwide. This generates a lot of money for the village and the Chinese government, thus making the village sustainable.

The Village has also transformed its identity from a local producer to a global producer of art work. This is highlighted through the villages Main Street, where the artworks are sold. All throughout the street there are many shops and artist selling thousands of pieces of art. In the past many local Chinese and Chinese business vendors would come to Dafen to buy these works. However, now thousands of tourists and businesses from various parts of the globe flock to Dafen to buy the artwork. They still sell reduplicated works, but the main focus now is on original artwork produced by the young local villagers. This gives the villagers and the village a new incentive to embrace art as a medium to expose their talent and identity worldwide. This generates a lot of money for the village and the Chinese government, thus making the village sustainable.