In “Cities in between Villages,” Marco Cenzatti proposes a process of urbanization different from the traditional model. (please follow up or introduce the different model immediately) Through examples of villages in the Pearl River Delta area (or PRD), he provides a path that can help villages avoid the destiny of becoming dilapidated “Villages in the City.” The PRD model contains various aspects unique to the Chinese political history, but Cenzatti argues that through the industrialization of villages, people can achieve the same result of an urbanized area as the traditional urbanization process. According to him, the villages will eventually become a sort of suburb where urban and rural coexists. In this process, villages will not only get to improve the physical neighborhood, but also have an active voice in deciding the direction of their urbanization.

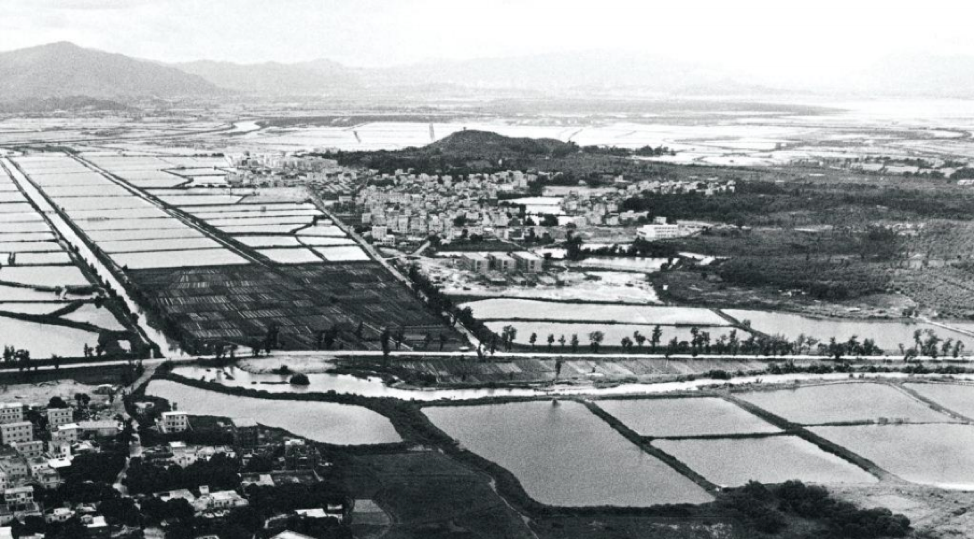

(please define and clarify a specific characteristic of the different model as the guiding topic for this section) Cenzatti points out that villages in PRD developed due to open-door policy and transportation infrastructure, while city development was limited at the time. Trade through the Township and Village Enterprises (TVE) helped villages accumulate capital and encouraged industrialization process. Helping to develop the trade relationship are the villagers who emigrated to more developed areas. Thus, villages in PRD became area of diffused urbanization. Image 1, although not from PRD, captures this change in action in a similar coastal area. In the picture, there are two sides: one with tall residential buildings in construction, one with existing village houses. The background of the right side, however, differs from the foreground in that there are already some newly built apartment buildings. Therefore, this is a village that has quickly developed through trade in TVEs, and large amounts of residential space is needed to accommodate the migrant workers contributing to the industrialization process. The wide and fresh-paved road provides evidence for the development of traffic infrastructure that Cenzatti claims to be necessary in the PRD urbanization model (still like to learn what type of model it is).

On the other hand, cities expand under the financial and political ambition of the municipal governments. Rural land is converted into “city” land as the only way to accumulate government wealth. (yes, can you make an argument based upon the comparison between the locally built urban villages and officially managed urban complex) The money raised is then used to build place-making projects such as monuments, museums, theaters, etc. Again, traffic infrastructure remains an important component here to help connect the larger city and to move migrants and workers between villages and cities. Eventually, villages get absorbed into cities as an industrialized district and not villages in cities. The author gives the example of Guangzhou and its Panyu County to prove this point. Panyu County started as a small village, but the open-door policy and development of transportation infrastructure boosted population and economic growth. On top of that, all those changes were planned and financed by the local government. By underlining the role of government, Cenzatti hints at how village governments can decide the fate of the village themselves. Image 2 shows a computer-rendered image for the plan for Wanbo City in Panyu County. It shows a residential, recreational, and commercial complex with skyscrapers, row houses, and large parks — all characteristics of an urban area. The fact that the Panyu municipal government can now afford to entire urban complexes proves that trade and transportation is a good way out for villages that might be on their way to be absorbed by the city.

Cenzatti presents the PRD model in a fairly positive light, where villagers, migrants, and the city all win because of the urbanization of villages. However, there isn’t a clear theoretical start for this development. Cenzatti attributes the economic development in PRD villages largely to the open-door policy in the 1980s, but it can be a lot more difficult for villages to compete with big businesses nowadays. Without the starting capital, it can be very difficult for villages to escape the fate of becoming a village in the city.