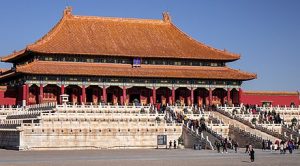

China’s modernization can be boldly compared to a revolution. This revolution is far from a grassroots one; instead, the development narrative, as told through many cities within China’s borders, document a top-down story. The nature of this city-wide modernization coincides with the erasure of both marginalized populations and traditional life. Previous discussions of village-in-the-city landscapes have described quite well the plight of migrant workers throughout China’s Pearl River Delta. Now, the focus rests on the erasure of China’s traditional roots. In “Cement Dragon”, a sculpture installation from Yang Yongliang, the reality of China’s traditional disappearance is salient. The artist, Yongliang, emphasizes that the rapid progression of the city-scape has, to a far extent, begun erasing China’s traditional roots.

“Cement Dragon” Yang Yongliang

The dragon in Chinese culture has persisted through time as a symbol of power and strength. Yongliang’s incorporation of this symbol as the main focal point of his sculpture allows for the viewer to first understand the significance of the piece. Above, we first see a Chinese dragon bursting through a cement wall. The delicate balance Yongliang strikes between a provocative foreground, the dragon, and a neutral background, the cement wall, persists as one of the core ideas of the piece. While the dragon symbolizes tradition, the wall symbolizes modern China and its built landscape. With the dragon, quite literally, breaking free from this wall, we may be able to interpret this as a way of the traditional trying to escape the modern; this idea, though, is ill-fated due to the dismal appearance of the dragon itself.

“Cement Dragon” by Yang Yongliang

This sculpture’s physical construction further echoes the contrast between traditional and modern; in some sense, it seems to shut away China’s tradition-rich past for the sake of bleak modernity. Overall, this piece is constructed entirely from cement, bricks, and steel bars(material) These elements are fundamental components of modern skyscrapers, alluding to the modern built Chinese landscape. Interestingly, we see not only the cement wall in the background clearly constructed from these elements, but we also see that the traditional Chinese dragon is, too. In fact, it appears that the dragon has a shaggy physicality due to the cement. Boldly, the dragon is cloaked in cement; the cloaking of such is far beyond the dragon’s wants. We can assert that the unkept nature of the dragon’s appearance suggests that traditional China is being overwhelmed and fully consumed by the modern built landscape.

“Cement Dragon” by Yang Yongliang

“Cement Dragon” is an attempt to critique the loss of tradition in the modern Chinese landscape. This erasure of traditional China has been driven largely by government regimes and large corporations. This piece begs us to ask who is making city development decisions? Maurizio Marinelli’s “Urban revolution and Chinese contemporary art: A total revolution of the senses” asserts that much of city development reflects the ideas and goals of a Chinese minority – those who can afford to make such decisions. In some sense, as Marinelli also describes, this revolution in the Chinese city-scape is similar to mid-20th century China during Mao’s era. In Yongliang’s piece, the cement dragon seems to be cognizant of this dismal revolution. It looks reluctant and quite scared to be succumbing to the revolution. On its face, we see a blank stare with furrowed eyebrows. Its mouth is open. Combined, the dragon seems to have paused mid-gasp, suggesting a hesitation to fully embody its traditional powerful nature. The process of modernity has completely dominated the dragon, far beyond the creature’s ability to counteract it. (the connection between the dragon and revolution)