We’ve discussed, at length, the role that Tiananmen Square’s size plays in establishing the Square as a socio-political gathering place. We have also discussed the iconography of different monuments surrounding the Square, as well as the structures tucked inside the Forbidden City, adjacent to the Square. The stark differences in construction of buildings around the Square compared to those inside the Forbidden City not only demonstrate ideas of imperialism and socialism, but I believe the shift in building practices are also signifying ignorance of China’s specific geography and the implications of being situated in a tectonically-active region of the world. The adoption of socialist architecture follows closely with the strict adherence of state and collective identity (strong statement)

Modeled with influences from the Soviet Union, buildings around the Square are monolithic in nature. The Great Hall of the People, shown below, towers in size. Elements of the structure, from the neutral colors, cement facade, and tall and repeated columns, harken to eastern European architecture, where emotion and culturally-significant colors, icons, and elements are stripped away; all that is shown is a neutral with state icons (flags, symbols, etc.) (and monumental)

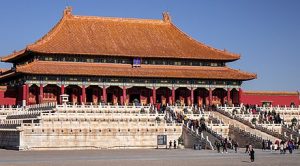

The comparison between socialist architecture and imperial architecture becomes interesting when we consider building elements that reflect China’s relation with the natural world. Structures such as the Great Hall of Supreme Harmony incorporate aspects of Chinese culture into the design, and, to a high degree, are antithetical to the structure, design, and influence of socialist-era buildings surrounding Tiananmen Square.

Though there is a noticeable shift from imperial architecture to socialist architecture, we have not discussed the importance of these shifts beyond discussing shifting ideologies. I believe the departure from imperial architecture to socialist architecture reflects a shift from connections to the natural world/environment to an emphasis on state ideology (good comment). China is situated in a tectonically-active region of the world. To accommodate the natural world in this capacity, imperial structures in the Forbidden City incorporate a building/architecture element called a duogong, which evenly distributes weight across a complex, crossing wooden tie. This design allows for weight to compress the wooden structures, preventing splintering, shattering, and breaking under intense shaking. Duogong elements are found at the top of imperialism-influenced structures, and the clear exhibition of these building elements reflects, to some degree, China’s historic connection to geography. As with other elements in imperial-influenced structures (colors, statues, iconography, etc), the incorporation of design is intentional and substantial. In socialist-influenced architecture, the connection to land and culturally-relevant icons in design are stripped. Instead, the only icons that persist are reflecting state-driven ideologies. The intentionality behind these structures, including the Great Hall of the People, the Monument to the People’s Heroes, and Mao’s Mausoleum, is reflecting state-shaped ideologies. Rather than emphasizing traditions, there is an emphasis on the state. The only colors that decorate the otherwise neutral, concrete, emotion-less structures are a blazing red, symbolizing the People’s Republic of China.

A bird’s eye view of Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City shows two contrasting, yet oddly similar, landscapes. The former harkens state-driven architecture, while the latter reflects culture, tradition, and connection to place. In our understanding of China’s architecture, we can begin to understand the importance of imperialism and that of socialism; by identifying present building designs and/or the lack-thereof, we can, again, comment on ambitions/goals/intentions during the respective time period. We could hypothesize that imperial China was rooted in historical identity, while, more modern socialist China was rooted in state identity.

comments: the work sounds strong and persuasive as the argument is clear and the visual supports. I see the persuasion when one discusses architectural issues via its language terms. in a short work like this, however, you may concentrate on the focal claim of comparison and contrast between the imperial and the socialist through a number of architectural elements, as we don’t have space to cover everything. there is also clear cut between the imperial and socialist as architecture calls for multifaceted reading potentials. any citations from the reading or other sources?