While it is important to acknowledge all four VIC landscapes, the discussion of visual aspects of each would require a lengthier medium, rather than a visual analysis post. My contribution for last week’s topic focuses only on two VIC landscapes: Gangxia, Shenzhen and Dafen, Shenzhen. Images from Laurence Liaw’s essay and from various photographers aid in a conversation of how VIC spaces respond to forward-reaching efforts of development and modernization, or, more generally, city modernity.

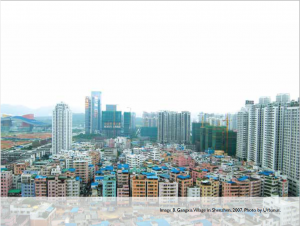

Laurence Liaw’s “Village-in-the-City as a Sustainable Form of Social Housing Communities for China: A Tale of Four Villages in Shenzhen” captures the existence of four very different Village-in-the-City (VIC) settings, Songgang, Gangxia, Dafen, and Honggang. These VICs have similar histories, broadly, but their persistence through time is subject to distinctly specific influences and adaptations, or lackthereof. Liaw spends most of his time documenting the evolution of four VICs as a way of emphasizing the loss, and subsequent importance, of social housing in Shenzhen, China. Coupled with the imagery within and beyond the article, Liaw’s argument allows for an understanding that VICs indeed are individual landscapes, but their presence, persistence, and battle against modernity is shared (Image 1).

Image 1: Gangxia, Shenzhen. From Laurence Liaw’s “Village-in-the-city as a sustainable form of social housing communities for China: a tale of four villages in Shenzhen”

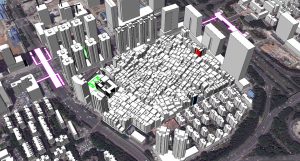

Image 2: Computer-generated image of Gangxia (center) and developed high-rises of Shenzhen (peripheral buildings). From https://grabcad.com/library/shenzhen-gangxia-china-city-mass-study-1

Gangxia and Dafen have both been encompassed by development, but these two spaces have responded in contrasting ways. The VIC of Gangxia is towered by surrounding high-rise buildings and modern developments (Image 2). In contrast, residential village spaces are ostensibly limited to set heights, around three-story height, often times with dilapidated housing frames/construction. Gangxia’s history is strongly influenced by the construction of civic centers and government spaces; the developing peripheral space has suffocated the development of the VIC community through high demand for housing and high land-costs. Dafen, though similar to Gangxia, has persisted through modernity in the formation of a collective VIC identity. As a symbol of this, the state of Leonardo da Vinci stand, encompassing Dafen’s core identity as a global art powerhouse (Image 3). From mere images alone, we understand that Gangxia and Dafen are responding to modernization in starkly different ways. While Gangxia crumbles to the ground (Image 4), Dafen thrives (Image 5). The collection of visual representations of these villages transforms the identity of the VIC spaces away from mere villages. We could argue that Gangxia will cease to remain a village in the near future and that Dafen, because of the communal core identity, appears to have molded into a thread of the larger city-scape.

Image 3: Statue of Leonardo da Vinci in Dafen, Shenzhen. From Laurence Liaw’s “Village-in-the-city as a sustainable form of social housing communities for China: a tale of four villages in Shenzhen”

Image 4: Man sleeping next to pile of concrete blocks, Gangxia, Shenzhen. Imaged by Jesse Warren. From http://www.shenzhenparty.com/blogs/shenzhen-party-info/66118-gangxia-west-village-photo-colle

Image 5: Corridor covered with various oil paintings in Dafen, Shenzhen. From https://www.szcchina.com/blog/dafen-oil-painting-village.html

Through images alone, we understand the liveliness of these two built landscapes. Gangxia is crumbling; its beige, neutral concrete blocks are strewn in piles throughout the closely-packed village area, while Dafen is vibrant. The paintings produced in Dafen paint Dafen, itself, in a bright light. Photographs of these built landscapes demonstrate two responses to city modernity: one that has fallen victim to pressures of development and another that has managed to remain autonomous and ostensibly self-sufficient. (if this is the central argument, then introduce it at the beginning) Can we expect all pockets in a city to persist through time? Perhaps not. We may be able to assume that there is some degree of persistence, whether that persistence is fostering continued housing and residential living or whether that persistence is through ruins. The persistence, regardless, is an aspect of city development. In the case of Shenzhen, visual reminders of different VICs and city-scapes continuously serve as a means of detailing how different communities have responded to the same pressures. It would be easy to assume all VIC spaces have responded in the same way, but these visual moments in time allow us to understand that each VIC, though similar with its original history, are not all that similar with adaptations to modernization and continuity with city modernity.