Credit: Vector Architects, Hybrid Courtyard, Baitasi (Pechino)

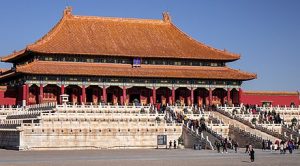

The image above captures, in clear detail, last week’s topic. The foreground shows a network of hutong arrangements in Beijing, while the background, lingering above, has a number of skyscrapers and high-rises. The contrast between residences beckons to issues of a modernizing society. Several elements elucidate this contrast, from the fish-bone network of the hutong to the blurriness of the skyscrapers under a cloak of fog/smog. Together, this image is aiming to demonstrate an eerie arrival of modern architecture; in that vein, in order to maintain a city’s distinct culture, what are ways these creeping ploys at modernization can maintain a city’s dynamic? From this image alone, it would be difficult to prescribe.

The structuring of the foreground and the background illustrates a means of a creeping future juxtaposed onto a sprawling past. There appears to be intentionality in the photographer’s depiction of this built landscape. A similar image could have been captured once the fog burned off during the day, yet, with the fog/smog cloak containing the skyscrapers, it seems as if these residences are a bleak omen for the future of the city. As the fog/smog cloak approaches, it will consume the hutong network below it, acting as a metaphor of the skyscraper’s encroachment onto the traditional residential network of historic Beijing. The hutong network is protected, but as the fog approaches, just as modernization does in the city landscape, the hutong will be suffocated. (if the fog/smog used as visual symbols, you may introduce it at the beginning of this paragraph)

This vantage point depicting the hutong against the larger apartment structure provides another example of a departure from tradition. In considering the layout of the traditional hutong structure, Liangyong Wu’s architectural analysis titled “Traditional Courtyard Houses and a New Prototype” describes the intentionality of these landscapes. In simplest terms, the network of alleyways, streets, and corridors collected within the hutong provides flow for the larger residential layout. There is a cognizant understanding of each street, with the ability to connect with neighbors and form an individual and communal identity. In stark contrast, the skyscrapers of Beijing’s modernized residential landscape hesitate to provide the similar aspects of flow and identity. The photographer of this image has captured the ostensibly chaotic, yet strikingly beautiful, network of hutong in the foreground. The vantage point favors this view over the view of Beijing’s skyscraper, which, from the view captured, provides a wall.(good point) We don’t gain a view of this particular built landscape’s arrangement. All we see, from a direct view, is the impermeable front that the buildings provide. While there may be intentionality in how these structures are designed and laid out, the vantage point of the image ceases to elucidate any of this information.

The fabric of Beijing’s built landscape has been hemmed under the influence of 20th-century modernization and industrial advances. The radicalization of the built landscape has provided stark contrasts between the traditional and the modern. China’s hutong network is under the influence of modern architecture, highly influenced from the West. To preserve traditional practices and customs, architecture must reflect earnest efforts to do so. In the image above, there is no sense of effort in maintaining a city identity of traditional customs and practices; instead, the built landscape is dichotomous, with the past under siege of the present. The photograph aims to show the ignorance of the modern built landscape with respect to traditional built forms, and, to some degree, this image aims to evoke a consideration of how cities progress into the future. (a wonderful work)

Image source: http://www.abitare.it/en/habitat-en/urban-design-en/2017/12/31/pechino-hutong-modernizzazione/?refresh_ce-cp

Liangyong Wu – “Traditional Courtyard Houses and a New Prototype”