[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/diotc-final-research-paper-print-copy.pdf”]

All posts by achen

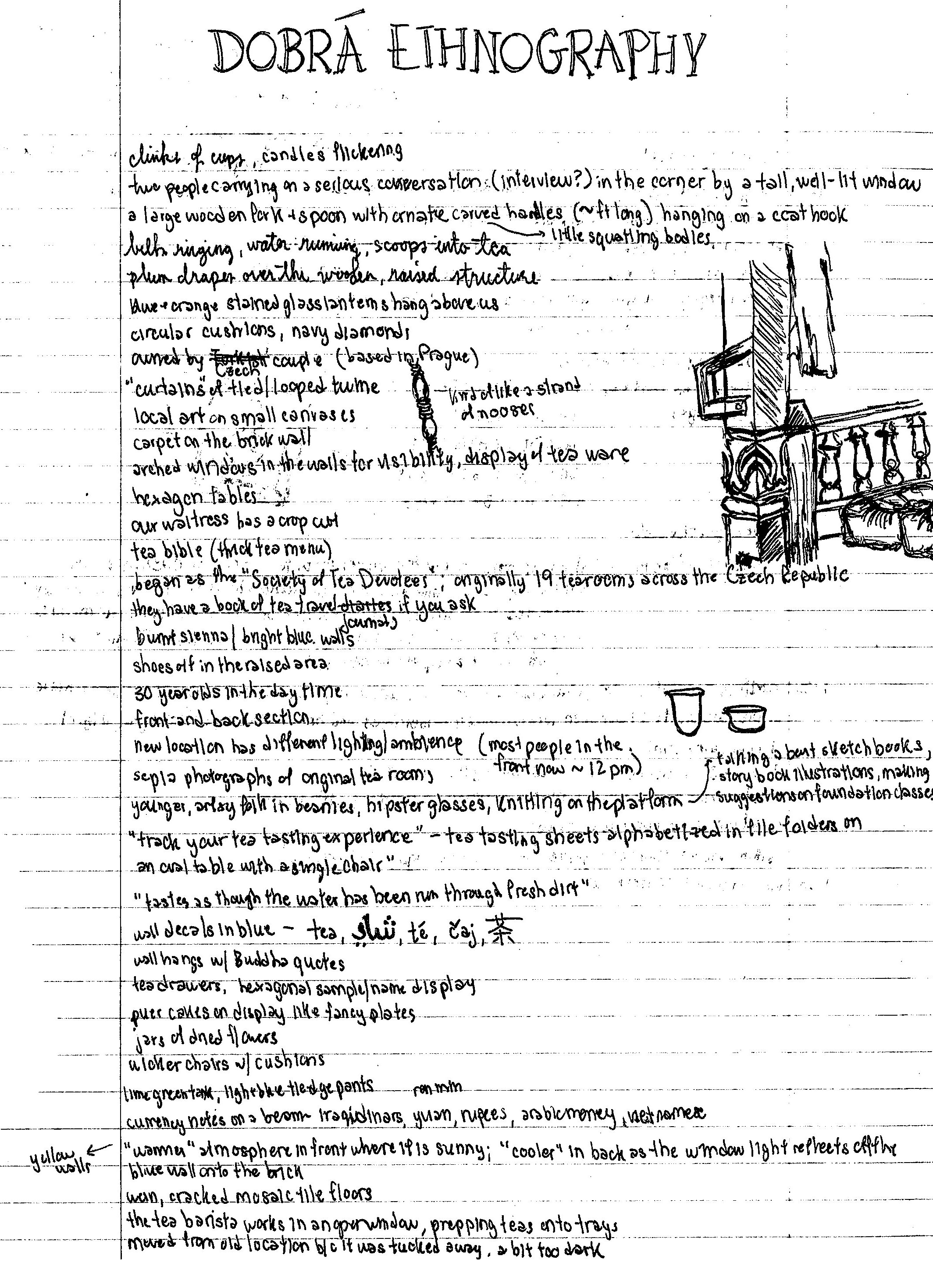

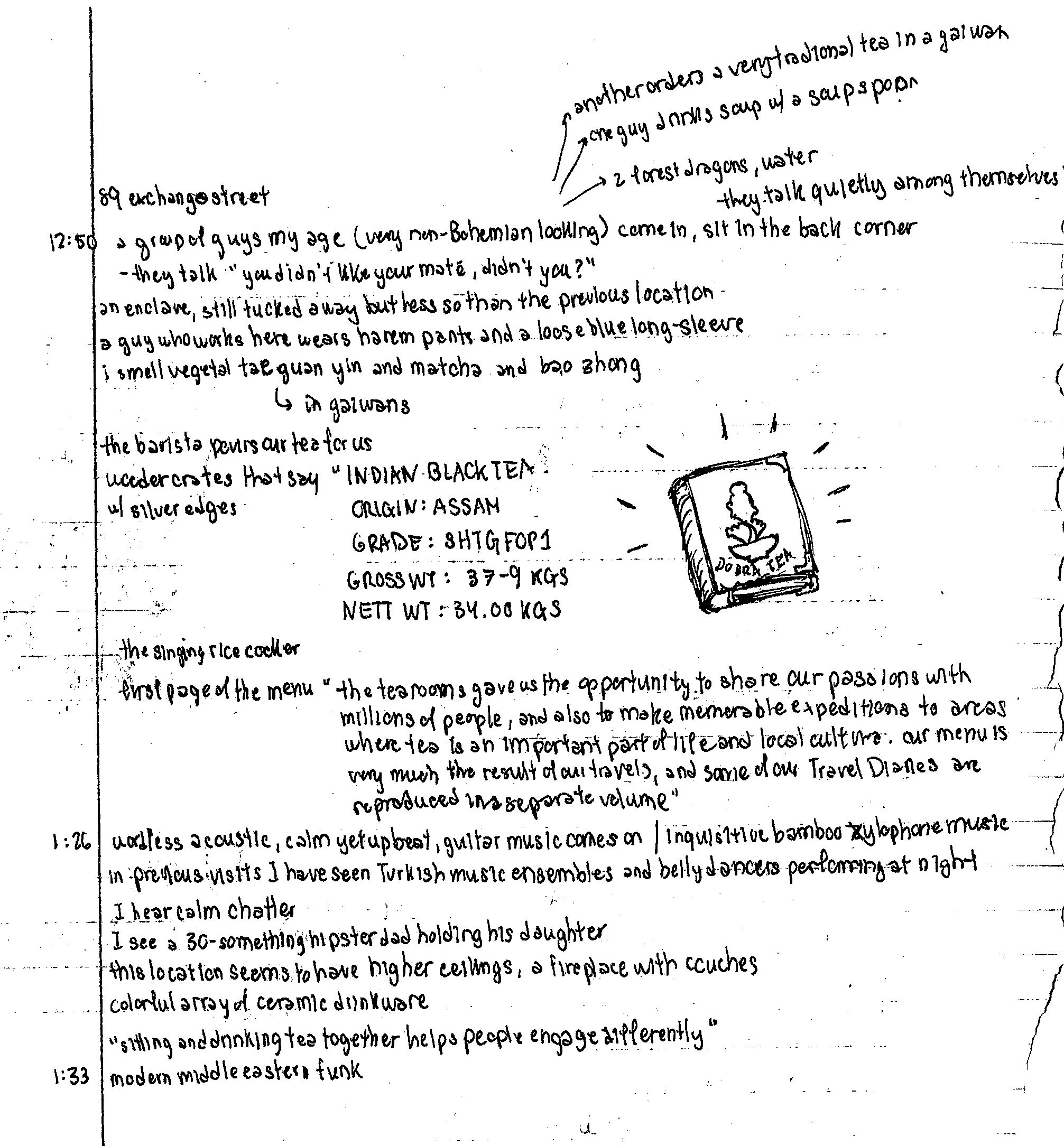

Dobra Tea Ethnography + “Bougies” and being “Classed” out of Portland

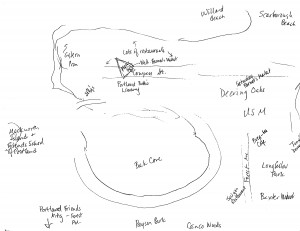

I have to say that speaking to Tom of Strange Maine and collecting a map from him truly affected me. I left the shop feeling ashamed that for so long, I had only had a narrow vision of Portland, its people and culture. We have learned in this class about gentrification, pointing out Munjoy Hill on our field trip, and here I was talking to a displaced native of that very neighborhood. He was honest and willing to talk, and never once slighted the “bougie”. But I could tell that he was sad and nostalgic for his Portland.

I wonder if Portland could be “cool” without gentrifying. The answer is easily no, because space is economically valued (according to views, proximity to desirable areas and topography) and money always wins. Where better to have the arts district and a stretch of upper-class restaurants than Congress, on the top of the hill? I had never even noticed that it was on a hill, since nothing had previously attracted me to explore beyond Congress, the heart of the city to me. Standing on that street, I am not only above socioeconomically, but topographically as well. The descent on either side of this “crest” is steeper on the side towards Cumberland Avenue, and dramatically different aesthetically. This parallel street is plain, average. This is where I saw modest houses and black people living their lives. On the other side of the “crest”, the streets slope more gradually towards Old Port and the water, where there is an interesting mix of places: boutiques catering to people brought in by cruise ships, gelato stores, a hippie chain shop (Mexicali Blues), specialty Himalayan pink salt crystal shop, a cheap pizza joint on the same street as Standard Bakery and tourist shops.

I also found that on the Western Promenade a beautiful little green space; anyone would be naturally drawn to it. It was so open, the setting sun was brimming over the edge. When I got there, I realized that I was practically on a cliff, and when I looked down I saw the pocket of strip mall and fast food joints I had encountered earlier. I was so high up, looking down at a place I had declined to explore further on my transect walk. The light did not hit what was below the same way it hit the patch of green I was standing on. I remember when the public artist we met on our field trip asked each of us where our favorite places where. I was surprised that we all chose places in nature. My favorite place is a hill in a Valley Forge Historical park, but when I stand atop it and look down, there is only more green below it. I feel as if anyone could stand on top of that hill with me and we could share the view; in that way it the word “public” is at its purest. Not just public by money-backed standards.

There are many exciting angles in which we can begin to improve Portland. But I think lost under those are solutions directed towards the displaced. Perhaps a smart survey project could be conducted which maps out the costs of what constitutes experiencing culture. The map would be accessible to all, an interactive map exploring all that Portland has to offer and allowing lesser known places more visibility. It should integrate quantitative data and direct, qualitative human input in order to show people that yes, the Asian grocer on the west end of Congress is worth visiting, and quite affordable if you need a snack. We need mechanisms that invite people to see an expanded vision of culture, and therefore disperse the concentration of money on top of the hill towards places that may not be as glossy and “nice”, but are rich with culture of another kind.

But now that brings me into confusing question of how to define culture. I am one to be easily blinded by the colors, lights and sounds of Congress St. While I do not have the means to visit every restaurant and pick through every shop, even if I am just strolling around, I can by my very upper-middle class background afford to feel as if this is somewhere I belong. And while I was standing in Strange Maine conversing with Tom, I was dressed in half in thrifted clothes in my ineffective attempts to maintain my outward self-expression while getting away from shiny, new materialism found in stores. I realized then that I cannot separate myself from the culture I grew up in (a very commercialized suburb of Philly), and nor can Tom. We both have our implicit definitions of culture, and they are quite different, but Strange Maine did seem to be an intersection between our two definitions.

There is cultural wealth and wealth of culture. Which would we rather have?

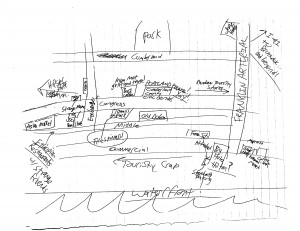

Kelly Arbor, 37. Queer, of Italian/French/Canadian/Lithuanian background. Change Artist and Barista Witch. Has lived in Portland for 4.5 months and is originally from Mexico, Maine. Leads Maine Educationalists on Sexual Harmony (MESH), whose goal is to “create a holistic integration of sex and identity and to (re)build a stronger community united with sex-positive awareness”. Used the word “mesh” multiple times in conversation. Made a conceptual map of places where he is planning events. Talked about “third spaces” (where one does not live or work) where he strategically plans educational “protests” so that they intersect target groups; for example, the street that Portland High School students pour out onto when they get out of school for the day.

Suggestion for Improvement: More bike lanes and green spaces.

Tom — caucasian, 30-something male who has worked at Strange Maine on and off for 11 years since it opened in 2003. Born in Portland, grew up in pre-gentrification Munjoy Hill, when people spoke of it as “slightly dangerous”. Likes avant-garde experimental music. Prefers grit in things. Commutes to work because he has been “classed” or “priced” out of the “peninsula proper”. Describes new Portland as having become culturally null, sterilized in a sense, and in a transitional state. “Same stuff in glossier packaging”. Nostalgically describes Congress St back in the day, and recommends that I visit Paul’s convenience store, a Maine-y place where you will hear Maine accents, where “bougie” people don’t go. We discuss other towns in Maine: “Everyone shits on Lewiston”.

Suggestion for Improvement: I did not explicitly ask. But if he could live in the place he grew up, that would be awesome.

Mary, 62 years old, caucasian. Has lived in Portland with husband for 35 years. Have two children with grandchildren. Opened a Quaker School on Mackworth Island (Friends School of Portland). We discussed gentrification: “Portland is an asset…need to bring money in somehow”.

Hunter, 19, caucasian male student. Considers himself a “foodie”. Would rather live here than anywhere else, because of its perfect size — small enough that there’s not much traffic or crime. “If Portland wasn’t gentrified, it wouldn’t be cool”.

Suggestion for Improvement: More means of transportation other than cars.

Who do you think you are, with your brick-colored paint?

Saturday afternoon, brisk sun. We embark on a tireless adventure of trekking through Portland. We “derive” without even realizing it, letting our conversations and instincts guide us through the entire peninsula as we searched for graffiti. I notice, however, that as we dig our ways through the back streets and barren Scandinavian-style architecture of Bayside, that there is nearly no graffiti. As we found ourselves further from places where we could easily identify that we were in Portland, we thought that we could have been just about anywhere. It was quite bleak, and the tags we did find were confined to the backs of crosswalk lights and signs. All were mere outlines of graffiti, quite inconspicuous and diminished in presence. I wondered whether this fact says anything about Portland’s identity — whether it is nebulous, minimal due in part to lack of racial diversity, or in transition. We speak to a woman with her bike who curiously asks about my research, and she confirms that there is nearly no graffiti in Portland. In certain places I see where larger graffiti has been painted over with brick-colored paint, or walls with mottled scars where it has been scrubbed off.

We continue our walk. Approaching the West End, the landscape transforms. We confront a pocket of strip mall, fast food joints, and ethnic markets. Here I find perhaps the best “graffiti” in Portland: an undersea mural across the walls of the Dogfish Cafe. It had the clash of three dimensional graffiti fonts, a crab against tendrils of kelp, and an unidentifiable sea creature against a gradient of blues and drowned clouds.

This was such a rarity that I thought it was imported.

We head up the hill back around to Congress Street, the new arts district that had encroached on one of my mappers’ (Tom; Map #2) fond memories of the street ten years ago, when Strange Maine had just opened. Congress had been lined with pawn and junk shops, and places like Paul’s convenient store and Joe’s smoke shop. Ten years later, my eyes are meeting beautiful examples of graffiti, the kind better defined as street art. There is a red, distorted “Nosh” dripping with blue splayed against the black facade of NOSH restaurant. Where Congress and High streets intersect, there is a curved wall of plywood with maze-like clouds, black “windows” looking into an sunset, and a crab battling a transformer atop a burning city.

Perhaps this is why none of it was removed; it gives Congress vibrancy. In all the places where I found minimal graffiti, it had been removed because it must have detracted from the image of the neighborhood. An already run-down looking gas station does not need graffiti to further depreciate or strengthen its image. Here is Lynch’s idea of imageability. Assuming that graffiti is the product of an urge to express, and having found evidence of Portland’s attempts to erase tags, the illegible signatures are sliced off the end of the spectrum (among the ranks of careless tagging and vandalism) of what can be considered graffiti to push Portland’s image to the more “refined” end. Hailing from the suburbs of Philadelphia, I know that graffiti may be considered street art, but street art is not graffiti. Original graffiti is saturated with the punk DIY attitude, a rebellion carried out by unschooled artists against blank walls to establish an invasion of their presence. Portland is too small for pockets of these rebels to be visible. If the visible art mostly exists behind the glossy windows of MECA and within the numerous galleries, I would say that there is a noticeable polarization in Portland in terms of what visible art gets to stay and what is erased.

Who gets to decide what graffiti counts as art and what does not? The people with the brick-colored paint.

Who do they think they are? Portland’s image purification and editing team.

Who are the creators of the graffiti that was erased?

Based on definition, public art is a reflection of those whose expression gets sanctioned, and graffiti is very much a reflection of those who does not get sanctioned. Though I could suggest that the city of Portland could use more aesthetic vibrance beyond the “bougie” areas, I think I would rather recommend Portland to find a way to attract more cultural diversity to Portland. Seeing how small this city is, in the next decade the outfluxes of people like Tom who have been “classed” out will leave Portland distilled with a narrow socioeconomic identity, to which Portland already seems en route.

When I asked Tom about his favorite towns in Maine, he noted Saco as one of them, where there is a significant Somalian community. This is a change he likes. I think Portland must also diversify its definition of culture. There is culture tied to money, and there is culture steeped in tradition. With this goal in mind, I would like to see an expansion of schools such as Portland High School, which boasts students from 41 countries speaking 26 different languages. If any public art project is conducted, it should be by the diverse students at this school. Their creations could even be a force of attraction for drawing even more diversity into Portland. In addition, if the city could also make an effort to create an area of the city in which a more “down to earth” arts culture can flourish, where people do not feel threatened by an elite, bourgeois vision of culture, and provide incentives for a diverse set of people to move there, the identity of Portland could expand instead of becoming polarized.

Urban Flow

Sorkin evoked the fundamental idea in urban planning that there must be a balance achieved in between “consensus and accident” [1]. He emphasizes that “public spaces are preeminently places of circulation and exchange…the idea of which is under siege due to economic and social privatization, identity politics and communitarianism” [1]. There is one detail he mentions in “Traffic in Democracy” which seems to delineate a path that modern society is taking that I do not think many people actively take notice of: that “public space has become abstract due to decorporealization” [1]. Somehow, the presence of pedestrians and free wills exerted over New York City crosswalks characterizes the city as a place of normalized chaos. To give the hierarchy over to cars by eliminating the crosswalks on 50th Street, however, is to yield to those who embody the modern transportation mentality: that cars are a symbol, vessel and incubator for self-empowered spatial and temporal “liberation”. It seems that motion sickness has developed into an anxiety due to lack of motion, and that there is a generation of restless urban nomads being created. Their sense of place, stability and home is changing as more of their experiences are dissociated from the reality on the sidewalk. For this reason, pedestrians deserve to maintain their rights of way, and the drivers should have infrastructural renovations conducive to flow.

Pathway infrastructure must be planned to enhance the flow of movement and decongest the city’s traffic, but at the same time express the fact that the “potential for conflict is vital” [1] to urban democracy. I see the city as a great big experimental work in progress, exciting because it is where cultural evolution is so accelerated, where all individuals are the actors. The enabling of flow must be intersected with choice, because exciting paths are never straight. Flow is not just movement but also direction and change, and that requires us to occasionally pause. Streets require nodes to intercept the flow, to guide those who need to get somewhere and to create spaces for wanderers in search of new paths. Abdul Maliq Simone said that “intersections defer calcification” [2], more so referring to the sort of thriving chaos in the city than vehicular traffic. Because with traffic, the drivers have choice in their paths. He also implies that there is an exchange people should be willing to make: Endure traffic and preserve the dynamism of the city, or let the busy roads rise to the top of the movement hierarchy and carve the streets into deep canyons.

[1] Michael Sorkin, “Traffic in Democracy,” in The People and Space Reader, ed. Jen Jack Gieseking, et al (New York: Routledge), 2014, 411-415.

[2] Abdul Maliq Simone, “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg,” in People and Space Reader, ed. Jen Jack Gieseking, et al (New York: Routledge), 2014 (2004), 241-246.

Visibility for the Preservation of Urban Identity

In terms of housing on the scale of neighborhoods, Smith’s ideas on gentrification paints a simultaneous mental renovation of a given area (Lower East Side being transformed into East Village) and marginalization of a disadvantaged group. The urban frontier mentality is driven by the greed of the real estate industry as they “smooth [the city] of its class and race contours” [1]. But when something is smoothed over, the excess needs to go somewhere. Robert Moses has demonstrated the ways in which the city is a shapeshifting microcosm, a place of accelerated evolution. The destructibility of physical structures is common and often necessary from at least one person’s point of view, but emotional geography and spatial-cultural history is an intangible beast to plow over.

I think there is a new mental mobility developing in urban folk — the nature of attachment is shifting along with its context. While it may be inevitable that neighborhoods will change, to promote the common good there must be a new space constructed for the displaced, and not space that is worse off or marginalized. Smith describes how the “terrain of inner city is valuable again, perversely profitable” [1] Smarting housing policy should be applied to the processes of reorganisation, in providing deserved compensation to those people. The difficulty here is that no one subtracts social costs from their profits. It is difficult and inevitably biased to quantify these costs, but the best basis to attempt it is the voice of the displaced. They may be offered money, but they are not offered the options, security and guidance they need if they are to be uprooted. Money can often be a bandage applied to a wound someone does not want to see.

In the first place, no, the Lower East Side should not have been subjected to gentrification that eventually wiped the neighborhood name off the map. They have their right to place. The juxtaposition of the Lower East Side to Greenwich Village — the edge between them acting as a source of friction — helped to preserve their history, visibility and identity by maintaining a geographic contrast.

Munjoy Hill was described in a Washington Post article as formerly “a onetime tent city” when Portland burned down in 1866, and a “blue-collar enclave” [2]. Now it is a neighborhood dotted with venues and coffeehouses, lavishly described in the article as a base for accessing the foodie thrills and homeware shops of Old Port and the Eastern Promenade — a clear advertisement for attracting young professionals to Portland. Avesta Housing, the developers responsible for building the new condominiums in Munjoy Hill are “pushing the boundaries of affordability” [3]. However one might want to take this, what sorts of options are left to the working class? I found a list of subsidized housing in Portland, and Avesta Housing has also worked to create spaces such as Bayside East (rent restricted housing for 55+ citizens), Butler Payson (income based rent for 62+ and disabled), Deering Place (rent restricted for families), Munjoy Commons (rent restricted), etc. [4]

See the list here: http://www.mainehousing.org/programs-services/rental/subsidized-housing

There is more research to be done on my part in terms of the economic side of things, but perhaps these projects can funnel more money into providing housing and programs for those who cannot even afford income based rent, and strengthening the projects already in place. The Portland Housing Authority offers Housing Choice Vouchers, which allow the disadvantaged choice in where they would like to live, and not just in subsidized housing projects [5]. At Logan House and Florence House, “Preble Street provides 24-hour support services to monitor the stability of residents, provide crisis intervention and conflict management as needed, and to assist residents in developing and enhancing life skills necessary to succeed in permanent housing” [6]. Florence House is a $7.9 million haven built through a collaboration between Preble Street and Avesta Housing to house up to fifty homeless women [7] .

[1] Smith, Neil. 2014 [1996]. “‘Class Struggle on Avenue B’: The Lower East Side as the Wild Wild West.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 314-319. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[2] Talcott, Christina. “In Portland’s Munjoy Hill, Do as the Mainers Do.” Washington Post. The Washington Post, 29 Mar. 2009. Web. 06 Oct. 2014.

[3] “Portland Housing Developers Struggle to Meet Market Needs.” Mainebiz. Mainebiz, 20 Feb. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2014.

[4] “Subsidized Housing.” Subsidized Housing. Maine State Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2014. <http://www.mainehousing.org/programs-services/rental/subsidized-housing>.

[5] “Housing Choice Voucher.” Portland Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2014. <http://porthouse.org/section8/housing_choice_voucher.html>.

[6] “Welcome to the Portland Housing Authority.” Portland Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2014. <http://porthouse.org/section8/project_based_vouchers_proj.html>.

[7] Richardson, John. “Florence House to Open Doors for Homeless Women – The Portland Press Herald / Maine Sunday Telegram.” The Portland Press Herald Maine Sunday Telegram Florence House to Open Doors for Homeless Women Comments. Portland Press Herald, 05 Apr. 2010. Web. 06 Oct. 2014.

Visibility of Portland’s Identities

In terms of housing on the scale of neighborhoods, Smith’s ideas on gentrification paints a simultaneous mental renovation of a given area (Lower East Side being transformed into East Village) and marginalization of a disadvantaged group. The urban frontier mentality is driven by the greed of the real estate industry as they “smooth [the city] of its class and race contours” [1]. But when something is smoothed over, the excess needs to go somewhere. Robert Moses has demonstrated the ways in which the city is a shapeshifting microcosm, a place of accelerated evolution. The destructibility of physical structures is common and often necessary from at least one person’s point of view, but emotional geography and spatial-cultural history is an intangible beast to plow over.

I think there is a new mental mobility developing in urban folk — the nature of attachment is shifting along with the context. While it may be inevitable that neighborhoods will change, to promote the common good there must be a new space constructed for the displaced, and not space that is worse off or marginalized. Smith describes how the “terrain of inner city is valuable again, perversely profitable” [1] Smarting housing policy should be applied to the processes of reorganisation, in providing deserved compensation to those people. The difficulty here is that no one subtracts social costs from their profits. It is difficult and inevitably biased to quantify these costs, but the best basis to attempt it is the voice of the displaced. They may be offered money, but they are not offered the options, security and guidance they need if they are to be uprooted. Money can often be a bandage applied to a wound someone does not want to see.

In the first place, no, the Lower East Side should not have been subjected to gentrification that eventually wiped the neighborhood name off the map. They have their right to place. The juxtaposition of the Lower East Side to Greenwich Village — the edge between them acting as a source of friction — helped to preserve their history, visibility and identity by maintaining a geographic contrast.

Munjoy Hill was described in a Washington Post article as formerly “a onetime tent city” when Portland burned down in 1866, and a “blue-collar enclave” [2]. Now it is a neighborhood dotted with venues and coffeehouses, lavishly described in the article as a base for accessing the foodie thrills and homeware shops of Old Port and the Eastern Promenade — a clear advertisement for attracting young professionals to Portland. Avesta Housing, the developers responsible for building the new condominiums in Munjoy Hill are “pushing the boundaries of affordability” [3]. However one might want to take this, what sorts of options are left to the working class? I found a list of subsidized housing in Portland, and Avesta Housing has also worked to create spaces such as Bayside East (rent restricted housing for 55+ citizens), Butler Payson (income based rent for 62+ and disabled), Deering Place (rent restricted for families), Munjoy Commons (rent restricted), etc. [4]

http://www.mainehousing.org/programs-services/rental/subsidized-housing

There is more research to be done on my part in terms of the economic side of things, but perhaps these projects can funnel more money into providing housing and programs for those who cannot even afford income based rent, and strengthening the projects already in place. The Portland Housing Authority offers Housing Choice Vouchers, which allow the disadvantaged choice in where they would like to live, and not just in subsidized housing projects [5]. At Logan House and Florence Street, “Preble Street provides 24-hour support services to monitor the stability of residents, provide crisis intervention and conflict management as needed, and to assist residents in developing and enhancing life skills necessary to succeed in permanent housing” [6].

It seems that Portland has great initiatives that are providing flexible options for people, dispersed throughout the city. Yet there are still so many homeless people. I hope that the “excess” maintain their visibility, or else they will be forgotten as people skim over the presence of homeless people in Portland. Over the process of housing being levelled and rebuilt, the goal of depolarization should always be kept in mind.

[1] Smith, Neil. 2014 [1996]. “‘Class Struggle on Avenue B’: The Lower East Side as the Wild Wild West.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 314-319. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[2] Talcott, Christina. “In Portland’s Munjoy Hill, Do as the Mainers Do.” Washington Post. The Washington Post, 29 Mar. 2009. Web. 06 Oct. 2014.

[3] “Portland Housing Developers Struggle to Meet Market Needs.” Mainebiz. Mainebiz, 20 Feb. 2012. Web. 6 Oct. 2014.

[4] “Subsidized Housing.” Subsidized Housing. Maine State Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2014. <http://www.mainehousing.org/programs-services/rental/subsidized-housing>.

[5] “Housing Choice Voucher.” Portland Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2014. <http://porthouse.org/section8/housing_choice_voucher.html>.

[6] “Welcome to the Portland Housing Authority.” Portland Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 06 Oct. 2014. <http://porthouse.org/section8/project_based_vouchers_proj.html>.

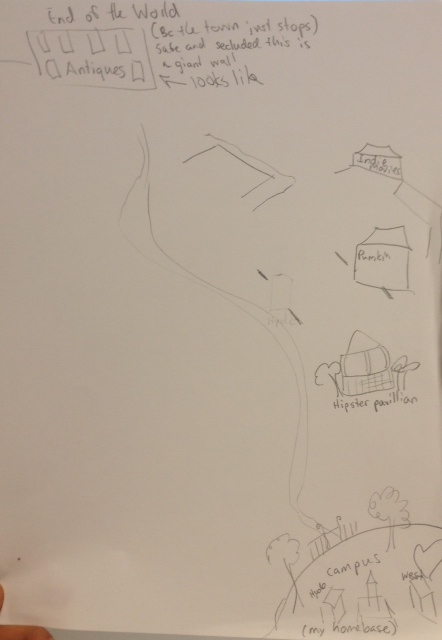

Brunswick Mental Map: Miranda ’18

The Fluid Public Sphere

I once took a drawing class in which we focused on negative space, bringing the spaces of the in-betweens into the focus of our creative attention. It becomes positive space, a product of boundaries, like the pieces of dough left in between after the cookie cutter has been stamped, almost discarded until someone recognizes its property value and potential. In light of the shifts away from local voices and influences that are the natural consequence of urban dynamics, certain physical spaces can work to preserve that democracy. Then there is the public sphere. Like a liquid, it takes the shape of whatever it inhabits. It is dynamic and fluid as it passes through various mediums. Just as Bryant Park used to be a water reservoir, the public sphere seeks a vessel to condense its particles into something shapely. It seeks a bridge to cross from abstract into visible. This fluidity is essential to change; it is universal and it means freedom. Don Mitchell states that “To fulfill pressing need, a group takes space and makes it public through its actions.” [1] Marches turn streets into aqueducts, protests transform space by spilling entropy into the environment, and mass gatherings in squares such as the Occupy movement turn the public attention to the negative-turned-positive space. But when these processes are are inhibited, they sap the vitality of the city.

It seems to me that public spaces should unite us on the basis of three foundations: Democracy, creation, and humanity. We can’t stamp out the bad things that go on in parks that have instilled fear in the joggers of Central Park or the indirect and direct victims of 9/11. We cannot hypocritically exclude people from those spaces that are deemed “public”. Maybe the best way to go about this, then, is to strengthen these spaces in their capacity to work towards mutual compassion. The production and exchange of compassion is by far simpler and much more immediate than money flows and physical restructuring. By eradicating the homeless from the park, we only understand them less and fear them more. Public spaces should promote confrontation rather than ignorance.

In constructing public space, there are important opposites to play on here. They are leisure and action, escape and remembrance, lighthearted friction and constructive friction. So, with all these ingredients, I think that the shaping of urban space should produce places that are loosely specialized for these three purposes, though there will be overlap, and that versatility is good.

I imagine that the democratic spaces will be fitted with platforms, tables and chairs, and complemented (not dominated by) with technology. There will be an amphitheater that will help to restore the public forum, constructed in such a way as to draw people into a circle. This shape promotes an a certain equidistance that lends itself to a feeling of collectiveness. A great example of this is the Swarthmore College campus’ beautiful green amphitheater.

As for the public spaces geared towards creation, I imagine community garden plots, chalkboard walls, installation art, and spaces for theater and music. It could be a new breed of the public forum, made for channeling multiple perspectives into a shared, final product. Art is reflective of all inputs and processes, and it invites its makers to make mistakes and forces them to accept them. The result is a synergized picture of the urban people.

And for the human spaces, they should cater to our most basic needs. Food carts and trucks, dog parks, running trails, farmer’s markets, chess tables, sports facilities. This group may also include memorials and gardens. We all need to nourish ourselves and we need space to dwell for the sake of dwelling. The essence of public spaces springs from what unites us beyond all boundaries, and it is only in spaces where the fullest of that essence can be expressed. Setha Low said it well, that “The emotional spirit should infuse the postindustrial plaza where all can find public expression.” [3] If Portland’s public spaces can be refitted to meet these three categories, the public sphere can continue to flow and take shape. Otherwise, urban agoraphobia will turn us into chickens in cages.

[1] Mitchell, Don. 2014 [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 196. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[2] http://www.swarthmore.edu/images/news/scott_amphitheater.jpg

[3] Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 172. New York: Routledge.

Spaceshaping

There are many forms of public space. A space on its own can attract people, but what people do within that space creates even more magnetism. I think the clearest path to take is to make these spaces more inviting, first physically and aesthetically. It is the atmosphere of these places that will form a solid foundation for the experiences they will foster. Then, the events that take place within these spaces should be amped up and diversified. For example, Portland in the summertime embraced National Pancake Day by giving out free pancakes. Friends of Congress Square Park is already doing a spankin’ job at organizing a set of events: http://congresssquarepark.org/events/. As for long-term goals, new spaces can be created, and in the design of their creation they can bridge disparities by their geographic placement.

- Rejuvenate existing space (seating, lighting, landscaping, food stands/trucks)

- More public events through all seasons, for all demographics (street festivals, “movies in the park”, parades)

- Create more space (dog parks, outdoor venue)

- Interactive Initiatives (community garden, interactive art projects)

- Create more community cohesion and collective identity

Smart design is essential to reshaping public space. There is plenty of room to overlap goals of community cohesion, sustainability and positive perception. What is exciting to me is the idea that local artists could collaborate with local children to create public art. Public art can be functional, aesthetic and sustainable all at once. What if someone devised a bike-powered light and installed it in that decrepit park that no one goes into? What if that park had hedges enclosing it and the fountain is redone with lights, and then artists create seating using unconventional (or even recycled!) materials? Leisure can be given a purpose and a place through venues and collective projects, and as an end result the people themselves gain purpose and a stronger sense of place. What if Portland had a dog park? No one could frown at a dog; animals have the power to draw people of all kinds together for a common love of waggling, smiling, excited bundles of joy. Seriously, dogs must get antsy in the city. So do people.

Side Note:

I am very partial to good lighting. As cities grow to be harsh, steely, angular jungles, shapers of public space should consider what makes humans gravitate towards a certain area. It should be comfortable, safe, welcoming. Light is a simple factor. Surely architects think about which direction their buildings face relative to the rising and setting of the sun, and I have certainly fallen in love with a city for as long as the best minutes of the sunset, when warm light pours down certain avenues or sheds a more human color to the city’s complexion. Portland is alive in the summer, and in the winter that liveliness disappears into a black hole. This is when Seasonal Affective Disorder takes a toll. The solution is light therapy: string lights, gas-powered street lamps and if possible, solar powered lighting. In the winter we are even more like moths to flames. The best lighting might draw out a path for us to venture along, rather than having residents be cooped up in their homes due to a lack of good light. And the importance of light should not be ignored; we are people of the earth and we should pay attention to the way in which elements of nature pervade us. Eva and I discussed this the other day in class. Would anyone want to stab someone under some ambient string lights? Hopefully not. But maybe under some harsh orange streetlights.

Positive Friction

One of the commentators in the Townsend lecture, Greta Byrum, stated that “Friction makes the city a vibrant place”. In Portland, Maine, identities you wouldn’t see normally see walking around are expressed on the streets at First Friday. Space Gallery brings alternative arts events, bringing about friction against our identities with creation and conversation. Congress Square Park held public World Cup viewings as a Jamaican food stand operated in the background, and standing in the background there is man dressed in black and spikes, standing right next to a group of people with Bibles in their hands.

Another commentator asked the question, “What is a city?”. The city is a conglomerate of people, and together it is a body — it has its heart, its extremities, its circulation systems. The buildings would be cold and the streets would be empty veins without human presence.

But anywhere you go there are fences in between groups of people. There is chain mail protecting “us” from “them”, which this erects invisible, yet stronger walls within their minds. I was once at an urban farm collective called the Mitten in West Philadelphia for a basement concert. The inhabitants of this venue were out in their fenced yard-garden, grilling burgers for the musicians playing that night. The street entrance to the garden displayed a sign announcing garden hours open to all neighborhood children on certain evenings. As I sat in that yard, a group of black children stood on the other side of the fence, pining loudly for a hamburger (although they were probably grilling veggie burgers). They were ignored. I wondered what I would have done had I been the one grilling. One of the children dropped his hand sanitizer on the soil bed within the fence, and he cried out “My hand sanitizer!”. Someone picked it up and handed it through the fence. I was uncomfortable sitting there. What were they thinking of us in that space? How was I supposed to react? Was it ameliorated by the fact there was a sign on the gate?

What unnerves me about urban growth is the decay of human connectivity. I have felt mystified by Philadelphia and I have also felt disillusionment, for having left the city feeling empty-hearted. But I am not from the city. The connection I sought on my visits was satisfied when I conversed with strangers, where people are brought together by a common love for the music, when a man in Portland made hot chocolate on a camp stove for people passing by. Public space is meant to challenge that inevitable separation and disconnection. The Mitten was a welcoming space on a certain evening, and on another it was private. Space varies with time, but a public space like a park tends not to move. I’m interested in these spaces because I believe that nature is the most undiscriminating public space we have; it is only when the green is surrounded by condensed grey that we pay closer attention to who inhabits the park and what happens within those confines. Townsend brought up a point that especially resonated with me: that urban developments should focus on making us more human and should encourage social cohesion. I think this is one of the most central ideas for urban planners and citizens to keep in mind. Public spaces and what is organized within them have the power to dissolve the perception of “stranger” and make people more compassionate about their neighbors. After having visited Preble Street today, I think it is even more important for “positive friction” to be happening. It allows for people to understand each other, instead of feeling threatened by differences and individual struggles until they are overwhelmed into a cognizant ignorance.