[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/bmiller_DIOTC_affordable.compressed.pdf”]

All posts by bmiller

Bayside Affordable Housing Proposal

Exploring Portland’s Bayside neighborhood to investigate housing conditions was eye-opening in several ways. Noticeable divisions between older, dilapidated homes and modern housing units brought a particular reality to my attention; Bayside, and the greater City of Portland, is experiencing financialisation and gentrification similar to many formerly “undesirable” areas of New York City. As shown by Neil Smith, fallout occurs when neighborhoods like Loisaida begin to change hands, most notably in the displacement of lower income populations to make way for development.[1] In terms of zoning, Fields and Uffer clearly illustrate direct conversions of subsidized housing into market-rate condominiums.[2] This is happening right now in Portland, and the city’s ongoing struggles with homelessness, elder care, refugee integration, and housing capacity will only become exacerbated by this trend if smart solutions are not implemented.[3]

Various bureaus of both the state and city housing authorities are already very open with affordable housing data (vacancies, prices, locations) available online.[4],[5] Unfortunately, this data is neither centralized, nor is it user-friendly. To serve the common good by aiding at-risk citizens of Portland in the search for homes, affordable housing data should be centralized, visualized, and updated regularly on a user-friendly map interface. Additionally, this interface would support filters for a user’s specific needs like handicap accessibility, family occupancy, or individual occupancy.

This smart solution would allow families to stabilize their living situation more rapidly and reliably, largely avoiding the burden of countless phone calls or time-consuming trips to the Portland Housing Authority office (not centrally located). In tackling this issue, there is no deficit of available resources for Portland citizens in search of housing, but a better system for utilizing those housing resources is necessary to support Portland’s low-income citizens. This solution would ideally be available as a smartphone app, online, and on designated iPads at resource centers. Having encountered large crowds at Preble Street, Avesta Housing, Oxford Street Resource Center, and Salvation Army on my transect walk, I believe these specific centers would benefit from providing this technology to clients, and thereby making the process of finding a home as personal it should truly be for everyone.

[1] Smith, Neil. “Class Struggle on Avenue B: The Lower East Side as Wild Wild West.” In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, New York: Routledge, 2014. 314-319.

[2] Fields, Desiree, and Sabina Uffer. “The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin.” Urban Studies July (2014): 1-17.

[3] Miller, Kevin. “Developer Wants to Build Market-rate Apartments, Commercial Space in East Bayside.” Portland Press-Herald, July 2, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/07/02/developer-wants-to-build-market-rate-apartments-commercial-space-on-east-bayside-lot/.

[4] Maine State Housing Authority. “Subsidized Housing.” Subsidized Housing. Maine State Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2014

[5] Portland Housing Authority. “Public Housing.” Portland Housing Authority. Portland Housing Authority, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2014.

Transect Walk: Varied Low-income Lifestyles in East Bayside

Ever since our class group visited the soup kitchen at Preble Street, I have been curious about poverty, homelessness, and refugee life in Portland. My initial surprise upon discovering the locus of Portland’s poverty problem was twofold: proximity and invisibility. More specifically, I was shocked to hear that Portland’s poorest neighborhood was only two blocks away from the shops and restaurants of Congress Street, and confused by the relative lack of dilapidation and other obvious poverty signifiers in Bayside.

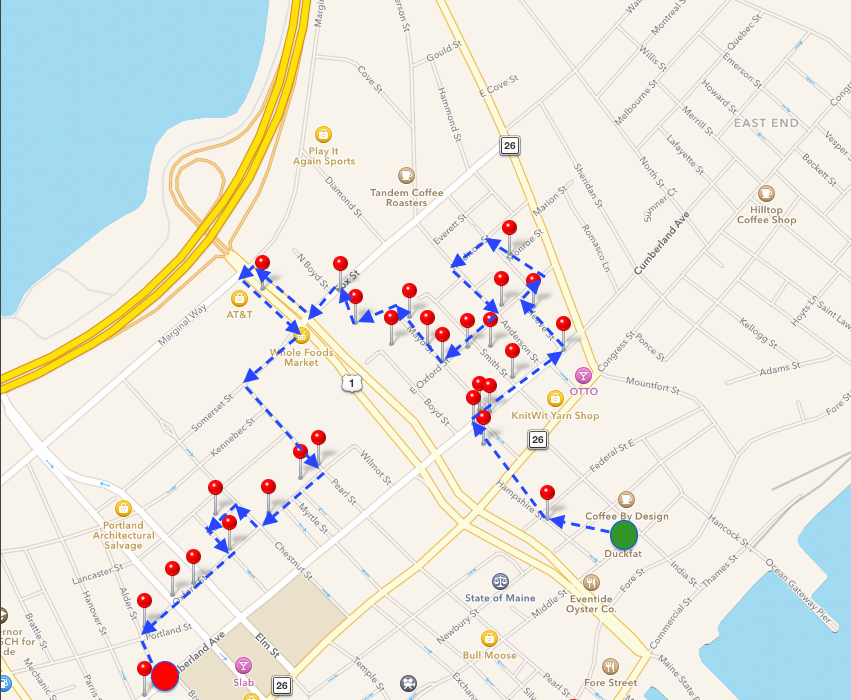

For my transect walk, I focused on housing as a means of investigating living conditions in East Bayside. There were, of course, limitations to judging housing conditions entirely by the homes’ exteriors. Nevertheless, my transect walk through East Bayside was eye-opening in that it showed the many forms and signifiers that low-income living can assume.

On East Oxford Street, for example, housing seemed to alternate between run-down (well built) multi-family homes, renovated houses with back yards, and shiny new condominiums.

Down Mayo Street, however, stood a low-income development that I could only describe as “Maine-style projects.” These apartments were all one story in a row, and reminded me a lot of some off campus dormitory housing at Bowdoin. The only difference is that these homes are supposed to fit whole families. There are a lot of different living situations that fall under the category of “low-income housing.”

My walk eventually took me past Whole Foods on Franklin Avenue, a sight which accentuated the undercurrent of gentrification that I felt upon seeing certain renovated exteriors in East Bayside. Ultimately, I walked the western portion of Oxford Street. Though not technically a part of East Bayside, this street is home to several homeless shelters and resource centers. I encountered more human activity, including sporadic gatherings of refugee families and shelter clients each block, and ultimately ended up at Preble Street. There I noted that the location of low-income resources is not residentially as underprivileged as East Bayside.

Colorful new affordable units buildings by Avesta Housing line Oxford Street. This, in my opinion, is the kind of the development needed in East Bayside. There are already proposals to displace low-income residents in order to build market-rate housing in East Bayside. Hopefully, financial interests will not trump the need for new housing I saw in parts of East Bayside.

Map of Transect Walk:

A Sunny Day on Congress Street and Alternative Living Situations

Simultaneous perception was a challenge in conducting my café ethnography. Instead of going about my business and taking notes every ten minutes, I found myself hyperaware of everything going on both inside the café and outside the gigantic window. In terms of housing, the location of Tandem brought up many questions about neighborhood, weekend wandering/flanerie, and demographics. Though I saw more racial diversity outside the window than I had expected, the clientele at Tandem were predictably homogeneous. Though I think Tandem is technically situated in the West End, its placement on a main artery made peoplewatching a more varied experience.

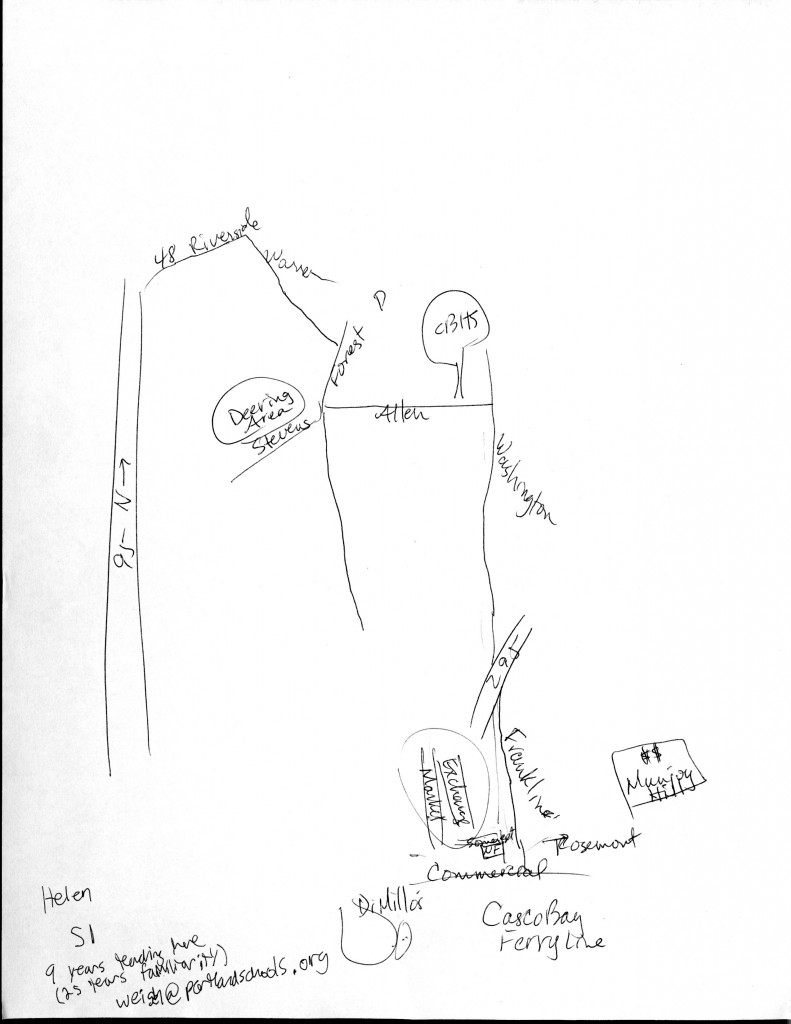

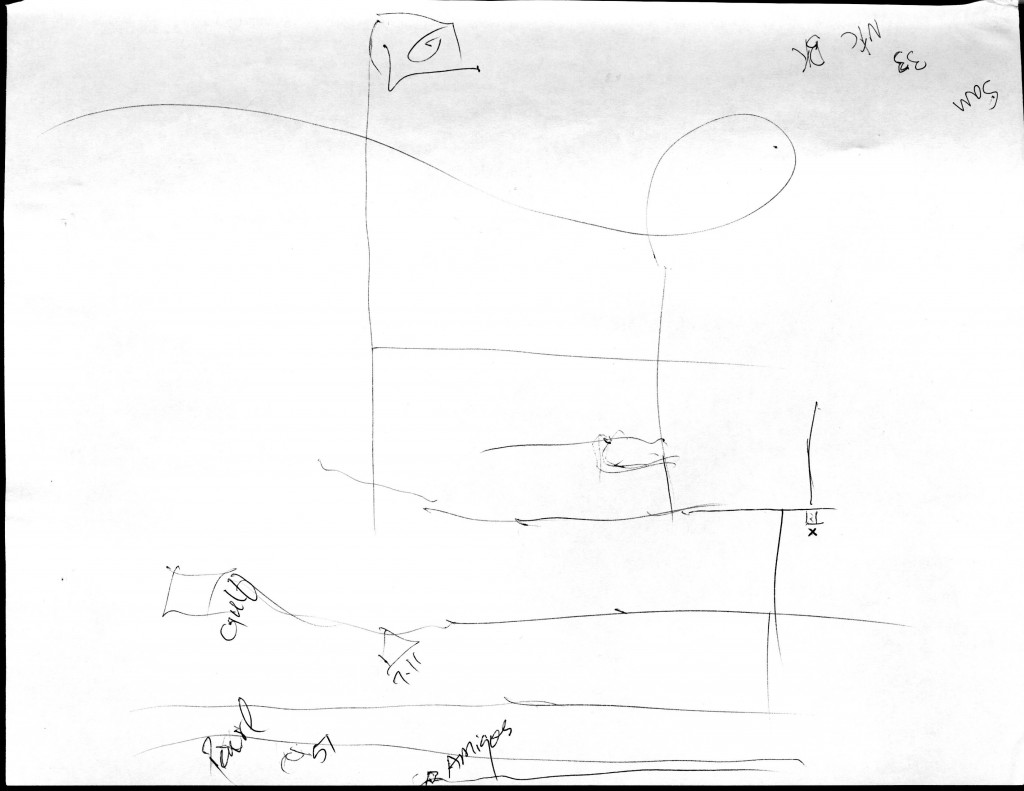

Mental map collection mostly yielded discoveries about the many living situations possible in Portland. Whereas I had expected to see several detailed maps that were telling in their inclusion and omission of certain neighborhoods and public areas, what I ended up gathering from my cartographers was more pertinent to housing than expected. For example, one can see below that Helen’s map is influenced heavily by the fact that she lives on a sailboat docked right outside DeMillo’s and once commuted further inland to CBHS via the highway. Sam lives and works at Bayside Variety Store, but a street of bars and clubs in Old Port were the first places he marked, and he marked no East Bayside locations at all. I was interested to see that living in Portland isn’t always a simple matter of finding an apartment in a shiny new condo, even though the future holds many new developments of that nature.

Café Ethnography: Tandem Bakery & Café (742 Congress St)

Saturday 9/27 @ 3:30PM

- I almost walked straight past the whited-out gas station awning of Tandem Bakery

- Walk in, immediately greeted with a friendly hello and enthusiastic conversation about their Malt Iced Coffee

- I watch the guy make it with all these beautifully curated tools and cups

- It’s really good coffee

- After sitting down in the more interesting corner bench area with low marble tables (impossibly small), I decide to move to the window counter with tall stools. I realize the whole place has really nice natural light, and feel pretty cool sitting in a former gas station store that is all bleached out and minimalist and stuff.

- A couple pulls up their car and leaves it unlocked, idling in a random spot in front of the awning, like we’re actually at a gas station. Nobody seems to mind at all. They come in, say some friendly hellos, and seem to order the usual. They are young, white, and clearly well off. They leave and get back in their little eco-friendly Toyota and zoom away happily

- Somewhat hip guy rides bicycle past a big brick house that was clearly a mansion, but is now for sale by KW real estate

- The music in here is solid and nostalgic

- Woman in headscarf walks by, wearing very cool Nikes. If I were to make a snap judgment, I’d say she belongs to an African refugee population here in Portland, but she is clearly integrated in terms of fashion.

- The baristas are talking about umami and something with a ragout…this town really cares about food.

- The pastries are sitting behind me, pretty much staring at me. The sticky bun looks really good. Maine for real. Even though I feel like I’m in Brooklyn.

- Apparently what I’m hearing are “records.” Of course

- Longboarding is happening in front of me. It’s so nice out that I’m not really surprised. This just doesn’t happen in Brunswick so much.

- I notice that the house across from me (that isn’t made of brick) is really intricate and somewhat Victorian/arts and crafts.

- Portland police vehicles keep passing by

- People really ride motorcycles on days like this too.

- Wandering is a popular activity on a Saturday (for some)

- Emily is sitting next to me. She has the impulse to write in this space. It is blank and therefore creatively open?

- A blonde family on bikes stops by, boosting the Scandinavian quality of the space. Families happen in this neighborhood, and they hall have their own cute little bikes. Classically cute little girl says something about “a long bike ride.” Mainers take advantage of nice weather when they can.

- Racial diversity out this window isn’t on par with NYC, but it’s noticeably better than Brunswick.

- Barista checkup: . All hip. Having fun together.

- Asian guy w/ glasses, top bun, blue running nikes.

- White guy with Red Sox cap and scraggly chinstrap beard.

- Black woman with big braids, lip piercing, big earrings

- The people who come in here are willing to spend $4 on a coffee. The café is not always full, but they do have consistent business. Some people can afford this lifestyle. They are all seemingly under the age of 50, and are mostly white.People are jogging by occasionally.

- The natural light is really doing its job.

- Okay these buildings across the street from me are literally ivy-covered. Portland was/is fancy. People on the street don’t match the fanciness that much.

- Portland seems very walkable, even though this street is clearly a feeder off some highway.

- Baristas share a secret code of theirs about a “cappuccino knife.” You don’t ever need a knife to make cappuccino, but you ask a coworker to pass you a cap knife when you’re frustrated.

- Like you are secretly pissed off and stabby

- Good to know

- Emily comes back from bathroom, comments on bathroom art and lemon verbena soap. Of course.

- Bus passes by at 4:10. “Metro Runs on Maine Natural Gas” Holy frack.

- It can get pretty calm in here. Just hearing the soundtrack and washing of dishes is kind of nice. I feel like I’m doing my homework in a restaurant kitchen.

- I don’t see nearly as many elderly people walking on the street here as I do in Brunswick. This one I just saw has varicose veins like a lot. Poor guy. He’s wearing a button-down though…

- Beginning to suspect that the African-American population here is more substantial than I thought before. Like just from who you see on the street.

- A lot of kids skate on these cobblestone streets! That seems bumpy.

- Some friends show up, as well as a carful of Bowdoin kids I didn’t expect to see. They are ecstatic. Coincidentally, the barista says to a member of the cast of Girls: Portland Edition that he is “very happy to be working here” as he caresses his La Marzocco machine.

- The place just smells really clean. Like water, alternately colored by the smell of espresso coming out of the machines. This is a bourgeois side of Maine that emulates many other styles. Most notably Scandinavia. It’s all white, but in a warm way. White walls + wood + white tile + plants. Green still makes its way into here, but not the typical Maine green coniferous growth you’d expect.

- Asked for a glass of water and the barista said “It looks like you guys are hangin’ out,” and handed me a whole nice bottle of cold water with one of those pop off caps. Maine manners are alive and well.

- Beanies n’ bicycles outside. Fixies too.

- Woman comes out of an apartment-looking building to smoke. What’s the housing makeup of this neighborhood (West End)? I see a lot of former mansions, but they no longer seem to be single-family homes. Tree lined streets and low buildings. Kind of like Brooklyn.

- A family comes in and the little boy wants a soda. Unfortunately, we are in hip Scandanavia, so all that ole’ top bun can offer him is a sweetened sparkling water. Tandem. I really like you, but I can see how some local people would hate you; namely these grungy Dakine backpack skater looking kids walking by. They probably think your coffee shop/bakery is bullshit.

- This location has been open for one month. Redheaded mom of white family (+ chacos & ankle tattoo) says “this place is so nice.” Barista says thanks, clearly having heard this sentiment all day.

- J Crew catalog model walks by in his best photo shoot attire, aviators and all.

- The bathroom has very interesting hanging practices. Portland strikes me as an aesthetically minded place, at least when people can afford to give a damn about that kind of stuff.

- I feel the need to walk for two reasons. My parking meter is running out, and activity on the street and in the café is slowing down considerably. As I exit, a man in a Bruins shirt and Red Sox cap with an absurdly small dog walks by. “Keep Portland just slightly weird.”

Mental Maps

Sharing the Sidewalk: Coffee Carts, College Kids, and Cigarette Breaks

As I read Michael Sorkin’s description of the democratized street experience in Manhattan, I could not help but think of my own block at home. I live right next to Hunter College, a major city university in Manhattan that enrolls around 23,000 full-time students and countless others pursuing part-time or continuing education programs, and the presence of the college in urban space is undoubtedly a factor in the formation of infrastructure on my block.

Sorkin describes how “stasis is the enemy of a flowing system of perfect efficiency, it is indispensable to its functioning: flow needs nodes” [1]. 68th Street is a high-flow area, especially at rush hour, due to the number of schools and hospitals due east and west of the 6 train station at 68th and Lexington. It does not, however, account for the many nodes of stasis and stagnation that occur on a daily basis, and interrupt flow significantly at rush hour. The de facto nodes that cease the flow of foot traffic on 68th include long lines at food carts (3), a bike rack (in constant flux), and a designated smoking area (on the sidewalk).

In some senses, the infrastructural architecture laid out by Hunter College accomplishes the conflict avoidance mentioned by Sorkin. Pedestrian overpasses, for example, allow Hunter students to move between campus buildings without creating traffic at crosswalks or interacting with vehicle traffic at all.

The student body of Hunter College accomplishes that which AbdouMaliq Simone describes in his concept of “people as infrastructure.” [2] The sidewalk infrastructure of my block is created by the daily practices and uses people find in that space, but it is also dictated by the planning decisions of the university. Due to a lack of garage space, for example, campus athletics and security vehicles take up most of the block’s parking spaces, day and night. Implementation of some open-source urban methods delineated by Alberto Corsín Jiménez would greatly benefit the efficiency and capability of the space surrounding Hunter College. Through recognizing the collective “right to infrastructure” in its abstract sense, developer feedback could greatly improve my block and several blocks in Portland. [3]

Speaking of Portland, though it may seem entirely unrelated to the heavy foot traffic of my block at home, it is clear that the small city has dealt with many similar concerns. The crosswalk addition in front of MECA, for example, was implemented eventually after the danger of students’ crossing Congress St. was made known to the city. This style of infrastructure change is indicative of a general trend in Portland’s urban feedback loop, which seems due for an upgrade. Improved bike lanes, sidewalk node management, and a more rigid enforcement against commercial vehicle parking would greatly benefit major thoroughfares like Congress and Commercial. Countless other ideas for Portland-specific urban improvement would undoubtedly come to light in a system of open-source infrastructure development.

[1] Sorkin, Michael. 2014 [1999]. “Traffic in Democracy.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 413. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[2] Simone, AbdulMaliq. 2014 [2004]. “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 241–46. New York: Routledge.

[3] Jiménez, Alberto Corsín. 2014. “The Right to Infrastructure: a Prototype for Open Source Urbanism.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (2): 342–62.

Balancing Gentrification and Smart Housing in Bayside

Many who visit Portland have compared the small Maine city to Brooklyn, and for good reason. From its townhouses, to its hip eateries, and the occasional cobbled street, Portland is not unlike the pop-culturized Brooklyn of recent memory. Additionally, the reality of Brooklyn’s rapid gentrification of low-income and ethnic neighborhoods (Bushwick, Greenpoint, Bed-Stuy) into yuppie enclaves is beginning to manifest more noticeably in Portland. Smith describes this phenomenon in the context of Manhattan’s Lower East Side:

As new frontier, the gentrifying city since the 1980s has been oozing with optimism. Hostile landscapes are regenerated, cleansed, reinfused with middle-class sensibility; real estate values soar; yuppies consume’ elite gentility is democratized in mass-produced styles of distinction. [1]

This reinfusion of funds, developer interests, and opportunistic middle-class individuals is happening right now in Portland’s Bayside neighborhood. Though it can be said that Munjoy Hill experienced a residential transition over past decades, Bayside is currently the next frontier in gentrification. An example of this can be seen in the recently approved development of the Midtown complex, a 650+ unit market-rate highrise project that has already rezoned a large parcel of land. [2] Bayside has historically been an industrial area of the city, and more recently has been home to subsidized housing for the city’s low-income population. [3] The area’s ongoing need for increased low-income housing is being answered with much smaller developments, like the 45-unit Bayside Anchor (36 low-income units, 9 market-rate). [4]

This emerging proclivity towards market-rate development in Bayside is a hallmark of gentrification much like the buyouts of rent-regulated housing described by Fields and Uffer. [5] Given the nature of whole market-rate developments like Midtown and mixed developments like Avesta’s Bayside Anchor, it is foreseeable that private equity investors will turn to rent-regulated units as potential sources of income. Activity of this nature would displace many of Portland’s low-income, minority, and refugee communities, just as it did in the loss of Loisaida. [6]

Nevertheless, frontier rhetoric has given supporters of such developments a means of justifying the displacement and razing of low-income home that will undoubtedly go on in Bayside. Supporters claim that more market-rate housing will help to ameliorate Portland’s 2% vacancy rate in rental housing, driving down prices across the board. [7] Somehow, it seems hard to believe that creating housing that excludes low-income families could be more helpful than large-scale housing initiatives tailored for those same families.

Additionally, it is unclear whether Midtown’s towers will be equipped with sensors or other smart technology to justify its existence and monitor its own footprint. One can assume that any new development is bound to have more modern systems built-in, which makes it all the more necessary to reconfigure the low-income housing in the area to support cost-effective, eco-friendly systems.

As Crowley, Curry, and Breslin note in their study of smart environments, “retrofitting existing buildings is costly[…]an alternative lower-cost solution is needed.” [8] Citizen actuation, however, may not be an effective substitute in working-class housing for a number of reasons. The aforementioned study seems to take for granted the resources and free time available to office workers, which would not be available to busy working-class individuals at home.

If the citizens of Portland would like to see the quality of life in Bayside improve for more than the gentrifying population, then a more balanced attention to enhancing low-income housing conditions will have to coexist with the financial interests of redeveloping the area. Widespread displacement of disadvantaged populations has happened before, in cases like Loisaida and parts of Brooklyn, but hopefully this transition in Bayside can be different.

_______________________________________________________________________________

[1] Smith, Neil. “Class Struggle on Avenue B: The Lower East Side as Wild Wild West.” In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, New York: Routledge, 2014. 314-319.

[2] Miller, Kevin. “High-rise Housing Moving Ahead in Portland’s Bayside Neighborhood.” Portland Press-Herald, August 14, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/08/13/high-rise-housing-moving-ahead-in-portlands-bayside-neighborhood/.

[3] Miller, Kevin. “Developer Wants to Build Market-rate Apartments, Commercial Space in East Bayside.” Portland Press-Herald, July 2, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/07/02/developer-wants-to-build-market-rate-apartments-commercial-space-on-east-bayside-lot/.

[4] Hoey, Dennis. “Portland Board Advances Plan for East Bayside Affordable Housing.” Portland Press-Herald, April 23, 2014. Accessed October 6, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/04/23/portland_planning_board_advances_plan_for_affordable_housing_/.

[5] Fields, Desiree, and Sabina Uffer. “The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin.” Urban Studies July (2014): 1-17.

[6] Smith, Neil. “Class Struggle on Avenue B: The Lower East Side as Wild Wild West.”

[7] Miller, Kevin. “Avesta Wants to Raze One Building, Then Raise Another.” Portland Press-Herald, April 22, 2014. Accessed October 5, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/04/22/avesta_wants_to_raze_one_building__then_raise_another_/.

[8] David Crowley et al, “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments,” in Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, ed. Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre (Springer), 379-99.

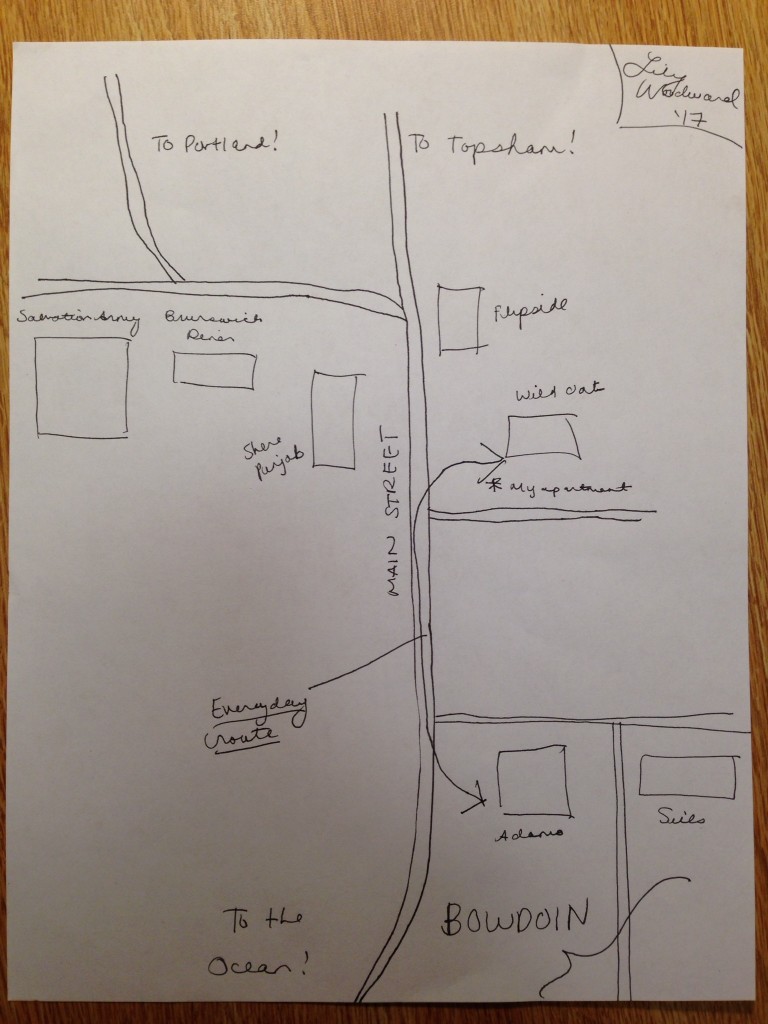

Brunswick Mental Map: Lily ’17

Access and Adaptability: Allowing the Public to Manipulate their Space

In its ideal sense, the smart city is engineered with efficiency and habitability in mind. Using technology, adaptability, and common sense, the smart city should inherently preempt the public “cry and demand” for change, constantly working behind the scenes to accommodate the people’s needs. [1] In reality, however, the well-intentioned solutions offered up by the tech companies and planners tasked with redesigning cities can often fall short due to their misguided assumptions about the public.

Design issues are all too common in the recent history of establishing public space. Although Battery Park, Zucotti Park, and Portland’s Congress Square Park were not created under the guise of smart design, they share a modern “design vocabulary” that actually suffers due to its own sleekness and limits their use. [2]Continuing to focus on these three examples, one can observe specific issues in each public space. Wealthy inhabitants of the Financial DIstrict almost exclusively utilize Battery Park. Zucotti Park was entirely faceless and useless until it served Occupy Wall Street protesters’ purpose. Congress Square Park was so underutilized that the City of Portland was willing to sell it to a private entity. These symptoms of restrictive design contrast greatly with the success of older public spaces like Union Square and Monument Square, which were designed long before minimalist smart design was even conceptualized.

This reality illustrates an important point about public space: it must serve many purposes in order to truly serve the public. In this sense, designing parks and intuitive gathering spaces for the modern city is more difficult, since even the most diligent smart city planner cannot predict how a space will be used. The “publicness” of space, as described by Setha Low, depends on factors of access, freedom of action, claim, change, and ownership. [3] By this model, a successful space for the public (not just a limited demographic) must be flexible, accessible, and central. In Portland, Monument Square satisfies those criteria with its liminal location between neighborhoods, proximity to public transportation and parking, and availability of city-owned open space. It was an ample home for the Occupy Movement in Portland, whereas Zucotti Park was chosen (despite its limiting design) for its proximity to Wall Street.

Monument Square is superior to Lincoln Park and Congress Square Park in that it allows “various groups to represent themselves” politically, socially, and recreationally. [4] This hierarchy of usability is seemingly backwards; one would expect parks to attract more of the public, but a paved treeless square ultimately wins out. Nevertheless, the square benefits from its centrality and flexible simplicity where deliberate smart designs have failed. Portland could see increased use of public spaces if they were redesigned to be more adaptable and more accessible; taking down the Lincoln Park fence could help, as could more events and flexible seating in Congress Square Park. Allowing the public to dictate the qualities of a space that is rightly their own will naturally lead to increased integration, representation, and recreation.

1. Mitchell, Don. 2014 [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights, and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 192-196. New York: Routledge, 2014.

2. Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Micheal Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 163-72. New York: Routledge, 2014

3. Ibid.

4. Mitchell, 194.

Smart Housing Suggestions for a More Livable Portland

Housing, being the largely privatized and personalized sector that it is, seems less apt for large-scale smart innovation than inherently more public issues like public transportation, recreational space, and municipal navigability. Looking a bit deeper reveals the possibilities in housing, from energy efficiency to streamlined affordable housing systems, where Portland’s city council can make meaningful changes. Here are five suggestions:

1. An app for finding and giving feedback on Portland’s new affordable housing developments (mentioned here)

2. Ocean-based geothermal heating in new housing developments (mentioned here)

3. An app for snow parking bans. Google maps directions to open parking lots and alerts about ban hours.

4. A shuttle system for transporting people home from their cars and vice versa during snow parking bans.

5. Energy Awareness Services in new housing developments to help residents visualize their emissions and consumption statistics.

I believe that the most exciting possibilities in housing innovation lie in the economic and environmental benefits of alternative energy and energy consciousness. Just across Casco Bay, Southern Maine Community College in South Portland is an exemplar of these benefits, having installed a sea water heat exchange system in the bay to power the HVAC in their lighthouse. [1] The upcoming Munjoy Street development [2], for example, could incorporate this system for heating/cooling and introduce Energy Awareness Services to create a culture of conservation while saving money for all new tenants.[3] Additionally, my first app suggestion would work well to gather new residents’ feedback about the HVAC system. This trifecta of innovation would make new developments affordable, eco-friendly, and open-data.

_______________________________________________________________________________

1. Beatty, Scott. “Harnessing Seawater: An Innovative Thermal Exchange HVAC System.” AASHE. May 17, 2013. Accessed September 25, 2014. http://www.aashe.org/resources/case-studies/harnessing-seawater-innovative-thermal-exchange-hvac-system.

2. “Housing and Community Development Committee Agenda.” Portland, Maine. September 24, 2014. Accessed September 25, 2014. http://portlandmaine.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Agenda/09242014-626?html=true.

3. “Objectives.” ESESH. Accessed September 25, 2014. http://esesh.eu/project/.

Exploring Neighborhoods: Trends and Exceptions in Housing

Neighborhoods have always fascinated me. Growing up in New York City, I saw that every neighborhood has a distinct (yet variable) reputation. Interestingly, neighborhoods and their reputations are almost entirely defined by the residential demographics of particular urban areas. Though exterior indicators of a neighborhood’s ethnic, socioeconomic, and cultural makeup are what we see when exploring the city as pedestrians, housing and habitation influence the type of businesses, communities, and issues that exist in a given urban space. As Hayden notes, dwellings’ “social history includes the builder, and also the owner or developer, the zoning and building code writers, the building inspector, and probably a complex series of tenants.”[1]

Walking through Portland and New York alike, the fluidity of transition between neighborhoods is truly astonishing. Not unlike the close proximity of Manhattan’s Upper East Side and Spanish Harlem, Portland’s West Bayside neighborhood is surrounded by commercial and residential wealth, yet remains the poverty center of the city. This was made especially clear by our experience at Preble Street, where Portland’s homelessness manifests poignantly just steps away from a Whole Foods, luxury condos, and major commercial thoroughfares. This ghettoization has everything to do with affordable housing, commercial real estate, and concentrated areas of low-income.

Project-wise, Hayden’s framing of housing as representation particularly intrigued me: “most can be learned from urban building types […] that represent the conditions of thousands or millions of people.” [2] In my research I would be excited to address the trends that can be gleaned from housing, while also grappling with the exceptions to those trends. For example, while the majority of data on a residential neighborhood might indicate a concentrated low-income immigrant population, the beginnings of gentrification may manifest in seemingly anomalous real estate or demographic data. Additionally, the example of formerly homeless men living in a historic India Street home through Preble Street’s Housing First initiative is another residential exception that is worth exploring.

I want to explore the ways in which neighborhoods become more or less desirable for different groups of people by examining urban diversity in all its forms. As for how smart city technology can play a role, I think I will have to revisit Townsend’s lecture to glean more specifics of how tools from companies (like IBM, Cisco, and Siemens) typically used for infrastructural purposes could help in the housing sector. Additionally, the role of individual developers as sources of housing innovation is worth exploring further, given their impact on the technological presence and efficiency of the MTA. [3] Tackling a rapidly growing population with the housing limitations that exist in both New York and Portland will undoubtedly require the aid of organizational technologies and efficient tools for finding housing.

1. Hayden, Dolores. “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” In The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, 14-43. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1997.

2. ibid.

3. Townsend, Anthony. “Smart Cities: Big Data, Civic Hackers, and the Quest for a New Utopia.” Lecture, from New America Foundation, Washington, DC, October 8, 2013.