Emma Chow

Professor Gieseking

The Digital Image of the City

12/17/14

Recommendations for Creating a Recreation Hub at the Foot of India Street, Portland, Maine

Research Question

Once a bustling commercial hub of industry, Portland’s historic India Street Neighborhood has lost its neighborhood vitality and is now in need of revitalization. The India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan, published September 2014, is comprised of five goals, six vision statements, thirteen development principles, and twelve critical actions.[1] This paper focuses on Critical Action 11 – Create a Recreation Hub at the Foot of India Street, by giving recommendations for developing the Recreation Hub to best align with the plan’s vision. The recommendations aim to meet the following goals and visions: Goal 5: Enhanced Mixed-Use Nature of Neighborhood; Vision Statement 5: A Healthy, Connected, and Active Neighborhood; Vision Statement 6: A Neighborhood of Strong Identity.

Integrating a workout park, green space, solar lighting, public art, seating, and small local businesses will create an enjoyable destination space for people of all ages. India Street Neighborhood (ISN) has great potential to leverage the vacant space at the foot of India St. to create a recreation hub that will effectively energize both the ISN neighborhood and the entire City of Portland.

Approach to the Common Good for the City

A city can serve the common good by developing its public spaces in a manner that allows Setha Low’s five freedoms[2] — freedom of access, freedom of action, freedom to claim, freedom to change, and freedom to ownership – to be realized. Cities must take measures to ensure public space maintains civilian safety; is accessible by all groups regardless of race, gender, age, or socioeconomic status; only allots temporary private ownership (i.e. evening or weekend events); and relinquishes power to the people for further shaping the space. Portland may be tempted to supplement limited government funding for public space with private dollars; however, the City should be wary of fostering any public-private partnerships that will turn its parks and squares into permanent large-scale advertisements. This may be especially likely given Maine’s regulations against billboards. Ultimately, government decisions should always be made to maximize the common good of the public, rather than the private.

Approach to the Smart City

A Smart City is one that first realizes the way technology can expand people’s potential well-being, and then implements technological systems with the goal of actually reaching this potential. The Smart City creates policies that incorporate and leverage available technologies to further the city towards where it wants to go[3]. Technology does not dominate the Smart City, but simply enhances the quality of the essential features of a city: infrastructure, housing, and public space. The Smart City uses technology to address issues such as poverty, urban food deserts, climate change, reliable energy supply, global communication, and transportation[4]. The most successful Smart Cities carefully adopt technology to help alleviate their greatest issues while still keeping people at the forefront of their decision-making.

The Smart City not only uses technology to install smart meters, coordinate traffic lights according to congestion patterns, and display subway wait times in real time, but also uses technology to enhance public space. For instance, cities can install free Wi-Fi in public space to improve Internet access and provide outdoor workspace, where tasks can be completed while surrounded by nature. Technology can be integrated into public space and shape the way people use that space. Technology can also be used to create a virtual communication platform for engaging the future users of public space in the planning process. Residents are the everyday consumers of the city, therefore, their voices should be heard – online forums and email surveys may be a great way to ensure the most voices are heard. Finally, the Smart City makes its data available to the public so people can develop apps to meet their changing needs. Apps can be designed to maximize people’s usage of public space, making them aware of where these spaces are located and what they can do there.

Literature Review

Academic Literature:

Green areas in cities are essential for sustainable urban development. Here, the word sustainable is used to describe cities that simultaneously ensure sustainable environmental, social, and human health. Additionally, green infrastructure both directly and indirectly, generates a series of economic benefits that will be realized in the future.[5] Accessible public space in cities improves the quality of life for residents by “facilitating social contact between people of all ages, both informally and through participation in social and cultural events (local festivals, civic celebrations or doing some theater work, film, etc.)”[6] Recent research has expanded experts’ understanding of well-being, revealing humans are social animals that experience an increase in well-being from pro-social behavior.[7] Well-designed public space provides a permanent site for consistent social interactions, thus further developing social capital and building community.

Public space can be designed to host an array of recreation opportunities, such as workout parks, walking and biking paths, children’s play areas, soccer fields, and open space for yoga classes. Green public space and recreation space can bolster the identity of a neighborhood, consequently creating a higher quality community environment for residents and attracting tourists and private investment, as well. When green spaces are installed, property values tend to increase: “Numerous studies have shown that housing and land value, which are adjacent to green spaces, may increase by 8% to 20%.”[8] Therefore, issues of gentrification need to be carefully considered when implementing projects for creating green space in cities. Other economic benefits include: savings healthier residents experience due to improved physical health, the revenues earned by vendors at cultural events, reduced storm water management costs, and increased spending by tourists.[9]

Waterfront cities have an incredible opportunity to leverage the natural water amenity as a means for improving residents’ quality of life. By facilitating physical and emotional contact with water, public waterfront space can foster strong relationships between urban populations and water. As a result, residents’ well-being is heightened by the enjoyment they derive from waterfront activities. Residents also gain an appreciation for the water and are subsequently compelled to protect the essential resource by changing their behavior and/or supporting water conservation groups.[10]

The success of public space is largely determined by its ability to meet people’s needs; the only way for planners to know those needs is by including the public in the planning process. Traditional image-based survey methods involve showing often biased, manipulated photos to participants; therefore allowing planners to elicit intended opinions from the public. Being able to say they involved public participation in their planning is often more important to planners than actually generating meaningful input. In Participant Driven Planning (PDPE), participants provide photos and are able to engage in meaningful dialogue about what they like/do not like about the places they present. Bottom-up planning processes, as opposed to expert-driven top-down approaches, ensure public space is designed to meet the real needs of the community.[11] Additionally, as MIT’s Places in the Making whitepaper concludes, the placemaking process is just as important for empowering local communities as the physical outcome is.[12]

Media Literature:

There is a national movement to “push back on the hegemony of the automobile and make public spaces accessible to pedestrians.”[13] Cities are increasingly realizing that designing for cars attracts more cars, while designing for people attracts more people. Great public space pulls people outdoors and then gives them a reason to stay – whether it be something to do, places to socialize, or beautiful scenery to look at. Many formerly industrial cities were built along the water for easy access to transportation channels, and now those cities are transforming their waterfronts to be multi-use areas for people.

Open space can be transformed using technology and nature to create dynamic public space that attracts tourists and residents alike. Three key features that need to be kept in mind when creating public space that will develop community attachment, are: social offerings, openness, and beauty.[14] Important features in any public space include: seating, lighting, and grass, plants, and trees. Many American cities are taking steps to create public space that offers recreation opportunities. New York City installed its first adult playground (an outdoor workout park) at Macombs Dam Park in the Bronx in 2010, and plans to install as many as two-dozen similar parks by the end of 2014.[15] Miami-Dade County, Los Angeles, and Boston have all installed public adult fitness facilities, as well.[16] The size and cost of workout parks can range from the $40,000 (the average cost per site in Los Angeles) to more than $200,000 (the cost of New York City’s largest park).[17] New technologies are even making it possible to install workout parks that generate electrical energy from users’ exercise on the fitness equipment; however, these technologies are not yet widespread since they are more expensive than conventional workout parks.[18] Workout parks are not the only solution for creating recreation space for adults. Boston’s Lawn Street D, for instance, offers circular LED-lit swings that change color according to movement, bocce ball, beanbag toss, Adirondack chairs, and a sound stage for music.[19]

Lighting can be used to transform public space at night. One team at the 2012 Makeathon in San Francisco designed an affordable technology for adding digital light projections to buildings and brighten up dark alleyways.[20] Another team at the same tech event offered technology to create a portable light up stage for performances in public space.

Methods

The Portland Master Plan and India Street Neighborhood Master Plan documents were first reviewed to understand the goals for the city and this specific neighborhood. Next, the History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood[21] was reviewed to gain familiarity about the history of the neighborhood and the important role the waterfront has, and continues to play, in developing Portland’s economic and physical landscape. An academic literature review was completed to provide insights into the economic, health, and environmental benefits of public space along the waterfront, as well as the importance of authentic public participation during the planning process. Media sources provided exposure into emerging technologies used for workout parks and lighting features in public space, as well as the value of placemaking for fostering community.

Conclusions about public space and opportunities to enjoy the waterfront were drawn from a series of data sets, including: consolidated data on the 97 mental maps collected by Digital Image of the City students and recommendations proposed by those 97 participants, as well as QGIS shape files provided by the City of Portland.

Maps were created to visualize the proposed area of development and guide planning recommendations. A map was first created to identify ISN and the future site of the Recreation Hub. Another map with a broader perspective reveals the extent and location of existing outdoor recreation space in the city, while contextualizing the Recreation Hub with respect to neighboring residential areas. The City of Portland provided data identifying the types of open space in Portland – areas identified as a trail, park, golf course, or playground were all grouped to map “recreation space”. Another map was created using data to illustrate the connection between different recreation spaces in the ISN area and the need for accessibility to the Recreation Hub. Bus route schedules were examined to understand the scope of accessibility.

Historical maps provided by the City of Portland were also referenced. These maps provided insights into how the city’s growth was fueled by the waterfront activity at the foot of India St and the commercial center of India St., Exchange St., and Middle St. Historic sources discuss the interplay between daily life in Portland and the waterfront; highlighting how it has changed from the eighteenth century to present day.

Findings

Historic maps and sources indicate that ISN’s identity as the city’s commercial center has changed over the years. Now, the neighborhood serves as a transitional area between the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Munjoy Hill and the tourist and commercial center of the Old Port and Commercial St. ISN lacks a sense of clear identity.

Fig 1. (Left) Portland in 1775 with India St. (King St. then) as a major artery to the waterfront. (Right) Portland in 1866 featuring the rail network along the waterfront centered at India St.[22]

As Fig 3. Illustrates, recreation space is concentrated around the Eastern and Northern edges of the city with very little in the center or along the waterfront. Piers and tightly concentrated streets dominate the waterfront. ISN is situated on the Eastern part of the city near the waterfront.

Fig 3. Recreation space (trails, parks, playgrounds, golf courses) in Portland.

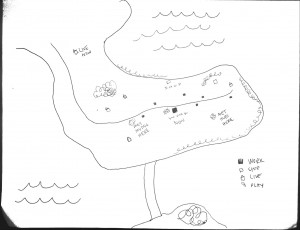

Fig 4. ISN and its major streets are highlighted, along with the site for the Recreation Hub.

ISN is dominated by open space that is not used for recreation and large buildings that consist of industrial buildings, parking garages, and hotels. There is no recreation space in ISN, there are only three recreation sites located just beyond the neighborhood boundaries. Residential neighborhoods border ISN, as indicated by the many small buildings to the Northeast and Northwest.

Fig 5. Bus routes, sidewalks, and streets connecting ISN to the rest of the city.

Bus route 8, which stops at Commercial St. and India St. provides access to the Recreation Hub. However, the bus only runs every 30 – 45 minutes on weekdays and 40 – 50 minutes on Saturdays, with no service on Sundays. Major streets in the area have sidewalks, but some are disconnected in and immediately around ISN.

Discussion

My recommendations have dual aims: (1) to offer feasible solutions for transforming the open space at the foot of India St. into a Recreation Hub, and (2) to suggest the optimal planning process for engaging public participation. I recommend installing an adult workout park, a play area for children, comfortable seating, lighting, and a storm-water collection pond. My recommendation for the planning process leverages technology and the web interface to provide a highly-accessibly and interactive platform for residents to voice their opinions.

The Recreation Hub needs to be developed with the goal of maximum usership in mind. The area can establish itself as a destination that draws people to ISN and gives them a reason to stay. Currently, popular restaurants, such as Hugo’s, Duckfat, and Eventide Oyster Company located on Middle St., are the main attraction to the neighborhood. The success of these restaurants, as well as nearby shops and the popular Italian landmark, Micucci Grocery Store, has already initiated a revitalization process; however, public space is still lacking. Even more, Portland as a whole presents limited opportunities for its residents to enjoy the waterfront. The water is a valuable natural amenity whose ability to improve quality of life should be better taken advantage of. Not only can transforming the open space at the foot of India St. into a Recreation Hub provide opportunities for people to spend time near the water, but it will also provide much needed opportunities for recreation.

While Portland does have some recreation sites, they are primarily located along the North and Northeastern edges of the city. The new Recreation Hub should include a workout park for adults, consisting of stationary equipment and signage providing exercise information. The workout park should occupy no more than a quarter of the total space. A play area for children should occupy another quarter of the space. Depending on budget limitations and residents’ desires, the play area can be as simple as a paved section for chalk or a sandbox, or full on playground equipment. The children’s area should be surrounded by benches for parents to sit on while attending to their children. At least half of the space should be made of natural materials. This includes open grass patches for picnics, bushes to separate the Recreation Hub from the street, flowers, and trees to provide shade. If space permits, a pond that collects storm water and then uses it to irrigate the greenery should be installed. The pond would minimize run-off and save water, as well as create a feature that children can interact with. Seating should be positioned around the pond so people of all ages can sit and relax, enjoying the calming effects of the water.

Lighting is essential, especially given the dark days of Maine during the late fall and winter. The City of Portland should partner with students at MECA, University of Maine, Bowdoin College, and Bates College and challenge them to create public art installations in the form of solar-powered lights. Different lights can be installed each season, transforming the look and feel of the space and showcasing many different student-artists. These installations would be an ideal way to incorporate public art into the space while minimizing commissioning and electricity costs and ensuring visitors’ safety.

It is critical that the Recreation Hub is made accessible to the rest of the city, especially as the most densely populated residential areas are located beyond the boundaries of ISN. While Bus 8 stops right by the Recreation Hub site, the bus does not run frequently and does not run on Sundays. Since the Recreation Hub will be catering to all ages, family visitation rates are expected to be highest on weekends when parents have the most time to spend time with their children. It would be advisable to increase the frequency of Bus 8, and at the very least, provide service on Sundays. The surrounding sidewalk network appears to be sufficient, however, the Recreation Hub needs to meet cyclists’ needs by offering ample bike racks. The Recreation Hub should also be well connected to the preexisting recreation area of the Eastern Promenade. This lookout area attracts many visitors and the Recreation Hub could become a final destination for these people, especially runners and cyclists seeking an additional workout. Establishing this connection and then educating the public about it will be key to increasing usership.

Finally, the Recreation Hub should be multi-purpose, capable of serving as an event venue year-round. Events can integrate local private businesses, to take part in food festivals. Similar the Art Walk model, one evening each month, the Recreation Hub could invite a selection of Portland restaurants to sell a few menu items at a capped cost. Temporary seating could be set up so people could pick up food from restaurant booths and then sit and eat. Musicians could be invited to provide entertainment. The food offering could be tailored to the season – outdoor heaters and blankets, Duckfat poutine, a hot chocolate stand, and snow sculpting competitions in the winter; Nosh burgers, a lemonade stand, and popsicles in the summer. This would be a good way for ISN to engage local businesses in community-building events without giving them long-term ownership to the space.

Conclusion

The recommendations detailed in this paper provide a means for Portland to significantly revitalize ISN. GIS analysis indicates that Portland needs to expand its green space and provide increased opportunities for residents to enjoy the waterfront as a part of their daily lifestyles. If the Recreation Hub incorporates the recommended features – an adult workout park, children’s play area, seating, green space, public art solar lighting, and an irrigation pond – the space will become a prominent destination spot for both residents and tourists. What these features finally look like should be determined by public preferences. Portland can best listen to the public by establishing an online platform that anyone can easily access to voice their opinions. The platform would become a forum where people can vote on options (i.e. four options for a children’s play area), comment on proposed solutions, and even post photos of places in Portland or elsewhere explaining what they like or do not like about it. Essentially, an online “public space” should be created to develop the public space to ensure people’s needs are best met.

The design of the Recreation Hub is critical, but accessibility ultimately determines its public usage. Thus, Portland should increase its Route 8 service to the Recreation Hub, ensure sidewalks are well maintained, and create a well-marked connection to the Eastern Promenade. Public awareness about the space can be increased through newspaper articles, newscast features, and events sponsored by local businesses. The Recreation Hub can become an engaging dynamic place for people of all ages to enjoy the waterfront, play, socialize, relax, and engage with nature. In these ways, the Recreation Hub has great potential to improve people’s quality of life and well-being. The recommendations discussed in this paper ensure the Recreation Hub will ultimately Portland help further ISN towards the goals and visions outlined in the India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan.

Works Cited

Beatley, Timothy. Biophilic Cities. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. 2010.

Cicea, Claudiu and Corina Pîrlogea. “Green Spaces and Public Health in Urban Areas.” _____Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 6, no. 1 (02, 2011): 83-92. _____http://ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/858207241?acc_____ountid=9681.

City of Portland. India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan. September 2014. _____http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/6471.

Durgahee, Ayesha and Matthew Knight. “New Gym Turns Workout into Watts.” CNN. _____November, 27, 2011. http://www.cnn.com/2012/11/27/world/europe/gym-workout-watts-_____electricity/.

Hu, Winnie. “Mom, Dad, This Playground’s for You.” New York Times, June 29, 2012. _____http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/01/nyregion/new-york-introduces-its-first-adult-_____playground.html?pagewanted=all&module=Search&mabReward=relbias%3As%2C%7B_____%222%22%3A%22RI%3A14%22%7D&_r=2&.

Hurst, Nathan. “Digitally Enhancing Public Spaces at the Urban Prototyping Makeathon.” _____Wired. November 6, 2012. http://www.wired.com/2012/10/up-makeathon/.

Larry, Julie and Gabrielle Daniello. History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood. Accessed _____November 17, 2014. http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/4276.

Low, Setha M. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial _____Plaza.” in After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, ed. Michael Sorkin _____and Sharon Zukin (New York: Routledge).163-172.

Perry, Tony. “San Diego’s Waterfront Makeover is Heavy on Public Space.” Los Angeles Times. _____December 8, 2014. http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-san-diego-waterfront-_____20141209-story.html#page=1.

Petty, Raven. “Four Cities with Playgrounds for Adults.” Livability. November 17, 2014. _____http://livability.com/health-and-wellness/four-cities-playgrounds-adults.

Rutherford, Linda. “Why Public Places are Key for Transforming Our Communities.” Greenbiz, _____April 25, 2014. http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2014/04/25/why-public-places-are-key-_____transforming-our-communities.

Sareen, Himanshu. “Smart Cities: A Brave New Digital World.” Wired, March 28, 2013. _____http://www.wired.com/2013/03/smart-cities-a-brave-new-digital-world/.

Schulkin, Jay. Adaptation and Well-being: Social Allostasis. Cambridge: Cambridge University _____Press, 2011.

Silberberg, Susan. Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities. _____Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013). _____http://dusp.mit.edu/cdd/project/placemaking.

Tomer, Adie and Rob Puentes. “Here’s the Right Way to Build the Futuristic Cities of Our _____Dreams.” Wired. April 23, 2014. http://www.wired.com/2014/04/heres-the-right-way-to-_____build-the-futuristic-cities-of-our-dreams/.

Van Auken, Paul, Shaun Golding, and James Brown. “Prompting with Pictures: Determinism _____and Democracy in Planning.” American Planning Association: Making Great _____Communities Happen. 2012.

[1] City of Portland, India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan, September 2014, http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/6471.

[2] Setha M. Low, “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza,” in After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, ed. Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin (New York: Routledge), 163-172.

[3] Adie Tomer and Rob Puentes, “Here’s the Right Way to Build the Futuristic Cities of Our Dreams,” Wired, April 23, 2014. http://www.wired.com/2014/04/heres-the-right-way-to-build-the-futuristic-cities-of-our-dreams/.

[4] Himanshu Sareen, “Smart Cities: A Brave New Digital World,” Wired, March 28, 2013, http://www.wired.com/2013/03/smart-cities-a-brave-new-digital-world/.

[5] Claudiu Cicea and Corina Pîrlogea, “Green Spaces and Public Health in Urban Areas,” Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 6, no. 1 (02, 2011): 83-92, http://ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/858207241?accountid=9681.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jay Schulkin, Adaptation and Well-being: Social Allostasis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 3.

[8] Claudiu Cicea and Corina Pîrlogea, “Green Spaces and Public Health in Urban Areas.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Timothy Beatley, Biophilic Cities (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2010), 6.

[11] Paul Van Auken, Shaun Golding, and James Brown, “Promting with Pictures: Determinism and Democracy in Planning,” American Planning Association: Making Great Communities Happen (2012), 2.

[12] Susan Silberberg, Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013), http://dusp.mit.edu/cdd/project/placemaking.

[13] Tony Perry, “San Diego’s Waterfront Makeover is Heavy on Public Space,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 2014, http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-san-diego-waterfront-20141209-story.html#page=1.

[14] Linda Rutherford, “Why Public Places are Key for Transforming Our Communities,” Greenbiz, April 25, 2014, http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2014/04/25/why-public-places-are-key-transforming-our-communities.

[15] Winnie Hu, “Mom, Dad, This Playground’s for You,” New York Times, June 29, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/01/nyregion/new-york-introduces-its-first-adult-playground.html?pagewanted=all&module=Search&mabReward=relbias%3As%2C%7B%222%22%3A%22RI%3A14%22%7D&_r=2&.

[16] Raven Petty, “Four Cities with Playgrounds for Adults,” Livability, November 17, 2014, http://livability.com/health-and-wellness/four-cities-playgrounds-adults.

[17] Tony Perry, “San Diego’s Waterfront Makeover is Heavy on Public Space”.

[18] Ayesha Durgahee and Matthew Knight, “New Gym Turns Workout into Watts,” CNN, November, 27, 2011, http://www.cnn.com/2012/11/27/world/europe/gym-workout-watts-electricity/.

[19] Linda Rutherford, “Why Public Places are Key for Transforming Our Communities”.

[20] Nathan Hurst, “Digitally Enhancing Public Spaces at the Urban Prototyping Makeathon,” Wired, November, 6, 2012, http://www.wired.com/2012/10/up-makeathon/.

[21] Julie Larry and Gabrielle Daniello, History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood, accessed November 17, 2014, http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/4276.

[22] Julie Larry and Gabrielle Daniello, History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood