[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Early-Warning-Weather-Sensor-System-Portland-small.pdf”]

All posts by edupliss

Paper Proposal

A SMART-CITY APPROACH TO SEA LEVEL RISE

As a waterfront city, Portland is especially at risk to the potential hazards associated with sea level rise. The question of combatting the effects of sea level rise isn’t a matter of “if,” but rather a matter of “when.” However, this is not a concern that needs to be left to the future, because Portland is presently susceptible to inundation under conditions of “storm-of-the-century” ocean surges.

In this research paper, I would like to explore the possibility of a tandem intervention for the city of Portland: the installation of meteorological and oceanographic sensors that would then relay and translate data into an interactive weather website specific to the city of Portland. I strongly believe that, through innovations in the use of existing technology, the city of Portland can create a weather-related warning system. This would be system that would allow its citizens to react quickly and prepare for possible storm effects.

Adam Greenfield, in is book Against the Smart City, suggests that technology should be used as a tool—a means to an end—rather than a solution. As a result, I am structuring this intervention as a tool to combat the effects of sea level rise, rather than as an urban-scale solution to climate change. It is meant to be an inexpensive, yet effective method of collecting, interpreting, and distributing data to all city residents, which they can use as they see fit to prepare and storm-proof their properties. It would also allow cities to stormproof , permitting them to anticipate public infrastructure at highest risk of inundation and erosion.

I have created a number of maps and data sets concerning inundation in Portland through my ArcGIS work in Eileen Johnson’s “Resilient Communities” course, and I would like to use this as the base of my data research. However, I would also like to explore and map the types of properties and infrastructure that could benefit from such an intervention; initial assumptions would show that areas in the Old Port and the Back Cove would greatly benefit from such a system. These maps would be used to determine how effective such a warning system would be for Portland’s citizens, and would offer a conjecture as to how such a system could be implemented into other, larger waterfront cities.

Cafe Ethnography

Cafe Ethnography

Location: Crema Coffee

Time: 2:30pm to 5:00pm

Date: Tuesday, October 21, 2014

—————————————-

2:30

First Post. Initial reactions to location: large, can seat up to fifty people (more space than a typical cafe), and mostly filled. Age groups represented are quite broad, with a large number of 18 to 25 year olds (20+ members) mixed with a large number of 50 to 65 year olds (also 20+ members). Must take into account that it is a Tuesday during a work week, as well as during the work day, so demographics may change over time.

2:40

The space is quite loud. This may be a result of the high ceilings, but people are not discouraged from talking to each other in this space. Cafes tend to have a library feel to them, as if conversations are expected to take place in a subdued voice out of respect for the people sitting alone. There are definitely people sitting alone in this space. There is a bar specifically dedicated to people who want to sit by themselves. However, many people are sitting in groups and are happy to talk in a normal tone. One might think that it would give the space a high school cafeteria feeling, but the essence of the cafe is not diminished by the lack of indie music playing in the background.

2:50

There’s a guy sitting next to me at the same table. He’s been sitting here for a while, not saying anything, looking out the window at the cruise ship in the harbor. In front of him sit a coffee and an iPhone—the typical mask of today’s city-goer. That’s not what interests me, though. Its the fact that he sat at the same table as me—without needing to ask—and it was okay for both of us. It makes me question just how many people, that I would assume are in groups, are sitting independently of each other. There is minimal sense of ownership of individual spaces by their users. Why? There may be several reasons. I think its because there are so few spaces to sit inside, and there are SO MANY people here in terms of a typical cafe. Odds are, I will not speak to this guy (he doesn’t look like he wants to be disturbed—everyone has those days, I can empathize). However, there is no awkward tension between us, despite our shared space, our proximity, and our mutual identities as complete strangers. I’m a fan of that. More spaces should be this welcoming.

3:00

I am seeing a lot of runners go past the window. Its lightly misting outside, but that doesn’t seem to be deterring anyone. The runners are all in their 20s or 30s. This tells me a lot about the location of the cafe within the city fabric. Granted, Portland is not large, which mean a 3-mile run could most definitely include Exchange Street as a part of a runner’s route from anyone living on the peninsula. However, their age corresponds directly with the age of the people sitting in the cafe. What this tells me is that Crema Coffee is also within walking distance for many of these individuals, which means that Exchange Street on the north side of Franklin Street sits in a neighborhood that has a large young-person population. The success of this establishment is proof of that as well.

3:10

I spent $4.39 on a small maple latte. ALL THREE of those words, associated with the price, are evidence of (dare I say) gentrification. As much as I hate the negative connotation associated with that word, I can’t deny its existence. I purchased twice the amount of liquid at Tim Horton’s in Topsham earlier, and it cost half as much. So why, oh WHY, was I willing to pay four times as much per unit of liquid for this beverage?? Well firstly, it was made with real maple sugar. That’s an added cost that is directly absorbed by the customer’s wallet. Secondly, the beverage, made with the same type of bean as my Tim Horton’s coffee, was called a latte. Marginally stronger, I’ll grant you, but no less similar. The name latte allows them to charge more because it is a specialty beverage. It is not the norm. Lastly, it was served to me with a fancy heart drawn in the steamed milk in the top. That’s the clincher. The effort to create that heart, however minimal, and the idea to add the superficial decoration (that adds nothing to the actual quality or flavor of the beverage) is reason enough to charge more than a standard coffee.

3:20

I just had a wonderful conversation with the elderly lady sitting adjacent to me at my table. This is another example of mutually shared space, but also a great example non-existent stranger anxiety within this space. We have never met, but we were more than willing to have a meaningful conversation following the simple question of connecting to the local WiFi. This probably would not have happened on the street, and it would definitely not have happened in a fancy restaurant. The cafe creates a sense of community. We are here for various reasons, but we are connected within the space by the welcoming aura .

3:30

I’ve seen many people walk in here, look around briefly, and then approach an individual who had been apparently waiting for them inside and proceed to sit down with them. This is important for the identity of the space. It has been recognized as a space of welcomed congregation. In doing so, it is creating repeat customers, who will frequent the space, spend their money here, and contribute to the success of the space. It also creates a node of the space within the fabric of the city.

3:40

The age group of the cafe has begun to shift. The younger people who were here in large numbers earlier have mostly departed. They’ve been replaced largely by members of the 50-65 year old age group—they represent about 75% of the people here right now. I’m sure this has to do with the cruise ship docked right across the street, but the number of flannel shirts I’m seeing suggests there are a good number of local users in here too.

3:50

The rain has been a big factor in the number of people here, I’m sure. However, I’m curious to see how the business is affected by nice weather. Obviously, people are staying inside because the rain keeps them off the streets. That would suggest there are people here that wouldn’t be here if there was nice weather. However, I would also speculate that the space benefits from nice weather too, because there are more people on the streets. Tourists definitely contribute to the business here, and they are probably deterred from venturing this far off the beaten path of the Old Port. I would venture to say there would be fewer locals in here if there were nicer weather, and MANY more tourists.

4:00

There are paintings periodically placed on the walls. They function as great decoration, off-setting the rustic brick of the walls and making the space feel a little more welcome. Each one also has a small, white square at its bottom-right. All of these paintings are for sale! This space isn’t just a cafe—its a functional gallery too. This cafe is the quintessential mixed-use space: it has so many varying functions that add to its usefulness, and also makes it a more attractive space. It is going to attract a wider variety of users, it will attract MORE users, and it will likely be more successful than a space that only offers coffee, only offers a place to sit, or only offers paintings for sale. All it needs is a performance stage in the corner…

4:10

The work day is nearing the end of completion, so new groups of people are beginning to pop up in the cafe. One of them is the casual business type. Pointed leather shoes, sports coats, and designer jeans are clear indications of someone with an “important job” and a very, very “disposable income.” They come in, buy their grande mocha-choca decaf latte double-shot with pumpkin spice, and leave. Probably off to an “important business meeting.” This is countered by the other group: the college student, specifically the artsy type. This group has an affinity for facial piercings, loose black beanies, fantastic hair, and outfits purchased at Goodwill for under $10. These students probably don’t have disposable incomes, but are also staying in the space much longer. They know the people who work here, and while they can’t necessarily buy the most expensive item on the menu every time they visit, they are definitely far more of a staple to the environment. They are contributing to the success of the business by their mere presence.

4:20

There is a completely different group of people in the space now than was here when I first arrived. Even the barista positions have changed hands. There are fewer people here than there were earlier, but the space feels just as active. There may be fewer contributing members, but the people here are far more often in groups than they were before. There are fewer individual users in the space, who were more likely to be silent and less likely to interact with the people around him. The people now, however, are gathered in mutual groups. These people are not silent, and are contributing to the white noise of the space even more than they were before. A line has formed at the counter now, though. I have a feeling that the space will start to feel spatially full once again, as well as resonantly active.

4:30

For the first time since I arrived at the cafe, the couch in front of the bay window at the front of the space is open. It has been occupied by a group for the entirety of my time here. I’m going to keep an eye on this: I want to know just how valuable this space is to the users of the cafe, and I’ll judge that by how quickly the space is filled up. INSERT: It took 90 seconds. And that’s being generous; it probably took less time than that. I’m astounded. My guess was three times longer than the actual time it took. That makes it three times more valuable than I first considered it (in terms of usefulness and desirability, as the space really isn’t “worth” anything to use). Imagine if we charged the use of space in a cafe by how much people want to use it, like we do parking lots or apartments? That would be the definition of degenerative gentrification, if you ask me.

4:40

As I reach the tail-end of my observations, I continue to see the same patterns occurring as I did earlier: people coming in and meeting people who have been here already for some time; a majority of young people balanced by an equal majority of middle-age people; business types who enter and leave, and artsy people who come in and stay in. Something I haven’t before that I’ve begun to see: people are moving seats. If they were sitting towards the back of the cafe, they are moving positions toward the front of the store. If they are sitting at dining tables on wooden chairs, they are moving towards the plush lounge chairs and coffee tables. As vacancies in more valuable spaces are opening up, people are taking advantage of them to once again create a natural scarcity in valuable spaces. It seems to be the natural tendency to migrate towards the more valuable spaces in the cafe; such spaces will not simply be left open if the opportunity to “conquer” them arises. Human nature, at a microscopic level.

4:50

The space has quieted down in the past hour. I can hear the background music for the first time since I arrived—its indie music, just as I expected. The space has gained more of the typical cafe aura, but it has not lost its identity as a place of congregation. Demographics remain the same, even if the total numbers have gone down.

5:00

The cafe is going to close in an hour. As a result, the staff is beginning its pre-closing routine: emptying garbage cans, washing empty tables, cleaning dishes and equipment, etc. More people are leaving than are arriving, as would be expected. The weather hasn’t really changed during the entirety of my stay, so its safe to say that my observations can be used as a summary for the majority of rainy days in this establishment. Given its location, though, I would wager that this place could function as a very successful bar on the weekends. It has the space and the atmosphere that would welcome many of the same people, just at a different time. A suggestion I could bring up to the proprietors of this business at a later date, perhaps…

Transect Walk

My transect walk took me on a sort of figure-eight route through Portland, using Congress street as the central “scaffolding” route and branching out in broad loops in opposing directions at its intersection with State Street. The focus of my walk was on the streets themselves. I then divided my focus in to a few groups: overall condition of the roads, width of street, existence of sidewalks plus quality and condition, and free street parking. **NOTE** I did not distinguish between no parking and paid parking (i.e. spots with parking meters), so as to draw attention to the distinct lack of free parking.

My walk started with a straight shot from one end of Congress street to the other, starting in Munjoy Hill past the cemetery and ending in the West End before Maine Medical Center. What I noticed along this stretch was an interesting dichotomy. At the center of my walk was Portland’s City hall. At this point, the street was at its widest—four lanes, two in each direction—with sidewalks paved in brick and/or large concrete slabs. There were no free parking spots, despite the numerous empty lots advertising parking (for a fee), but other than that the quality of the streets were in superb condition.

Outward from here, in either direction, these street roles began to reverse. Street conditions alone began to deteriorate, especially at the furthest points from the center along my walk. At my turn-off onto Park Street, there was even a pot hole large and deep enough to expose the original cobblestone pavement that was otherwise covered in asphalt. The width of the street became constricted, allowing only one lane for each lane of traffic. The sidewalks also constricted in overall width, and as the red-brick inlay was replaced by solid-black asphalt a few blocks in either direction from City Hall, the condition of the sidewalks worsened as well.

At the same point of transition (Franklin Street to the north, State Street to the south) came an influx of free parking spots along the street. On Munjoy Hill, free parking was available on either side of the street, with little to no time restriction. However, despite a marked improvement over no parking whatsoever, the spaces were still limited considering the number of potential users, i.e. people living in street side apartments, restauranteurs, etc.

Upon turning onto Weymouth Street, the street conditions along Congress Street have reached the furthest negative extent of the aforementioned street condition dichotomy. At either end of Weymouth Street are Maine Medical Center and the Exposition Center (aka Seadog Stadium). As a result of these landmarks, the streets beyond these points see an improvement in width and condition(with little improvement in free parking or sidewalks). Moving north once again along Park Avenue, these conditions are maintained through the turn-off onto State Street. At this point, the conditions once again change—this time unexpectedly. The street sidewalks improve in width and condition, showing the return of brick-inlay pavement, and free parking shows up on one or both sides of the street. Turning onto Spring Street introduced the return of wide, multi-lane streets (although traversing it is made difficult by a high median running along the area with the highest pedestrian and vehicular traffic) and the disappearance of free parking. As Spring Street enters the Old Port, the streets narrow once again (just after the Union Street intersection) at which point Spring Street becomes Middle Street. The trend of narrowed streets, minimal free parking, and brick sidewalks continues until India Street. At this point, I turned upwards and returned to my starting point on Congress Street.

As a side note, I also took note of the existence of bike racks along the street—which was easily done, because the only one I saw was at the Cumberland County Civic Center on Spring Street. There were many bikes locked along the side of the street, but these were often locked to trees or nearby stoop fences (especially along State Street).

People-Friendly Roads in the Old Port

This is the image that comes to mind anytime I think about infrastructure. Unfortunately (or luckily, depending on your perspective of the subject) goombas and koopas aren’t quite the infrastructural issues that smart cities have to deal with. AbdouMaliq Simone would even suggest that the infrastructure of modern cities isn’t necessarily just the the streets, the pipes below them, and the electric fiber and fiber optic cables above them both: it can be the people of the city too. (241) Portland, Maine is a fairly homogenous area: even with the East African migration to the area, the city still remains largely white with a fairly large middle class—hardly the class dichotomy that exists in Johannesburg. However, what’s important to realize is that the people share a common reliance on cars to travel to and fro, regardless of distance. What’s also important to realize is that Portland is hardly organized in a way that plays to the benefit of this reliance.

In terms of this infrastructure, I believe that Portland could benefit heavily from a pedestrian/biker-friendly development project. Michael Sorkin suggests that cities (neighborhoods specifically) should be constructed “in a way that binds them to the [human] body and what it can do.” (415) In this case, I interpret this in a way that makes the body a positive attribute in navigating the city, freeing us from the constriction of vehicular movement through naturally human spaces. Many of the streets, especially in Old Port, are cramped, narrow, and one-way, making passage with a vehicle difficult in the first place. In a different direction, Exchange and Franklin Streets represent two of the city’s most obvious boundaries (aside from I-295) and are more or less un-crossable by all but the bravest walkers and bikers. Ironically enough, Mainers would obey crossing the street if there were stoplights and walk signals, but less than a quarter of the crosswalks are supported by these traffic signals. A step from which Portland would benefit would be to close down many of the more narrow streets within the city to pedestrian and bike traffic (much like Bowdoin’s campus) and narrow the Franklin and Exchange street arteries to two-lane roads. A step like this would likely not increase traffic and would even encourage Old Port users to walk the city from the periphery rather than drive to the center and branch outward (which is safer and more practical, for all parties involved.) Bike lanes would also encourage a go-green alternative to driving to work, which would declutter traffic routes, benefit the environment, and encourage a healthful form of exercise. Imagine that—city planning as a solution to America’s “obesity epidemic!” What’s important for Portland to realize is that it is a small and navigable city, and increased vehicle traffic will actually have the opposite effect of decreased traffic: it would discourage users from visiting the city on the bounds of having to navigate the streets and compete with bikes and walkers on the quaintly congested streets of the old city. Even with the cold Maine climate, Portland’s size makes it tolerably navigable by foot and bike even during the winter. If Mainers have any doubt about that, here’s a picture of Copenhagen in January:

Doable? I think so.

Also, even though there is an aspect of Portland that embraces its cobblestone streets, we should recognize that there are smart city options to paving our streets and taking better advantage of our impermeable surfaces. This video details one such smart-city solution:

Its easy to see how such a technology could benefit a city like Portland. Massive solar panel arrays equal big savings in energy expenditure in the long run, and since the buildings in Portland are pretty short, the amount of time that our streets and parking lots would be exposed to sunlight is much higher than in most any other city. The passive snow removal technology would be a huge bonus, saving the city thousands and thousands of dollars in snow removal using clunky plows, followed by massive expenditures in repaving every few springs as a result of the plow’s damaging effect on the roads. No need to salt the streets either, which would be an added bonus to the environment! Portland is a small city, so implementing a technology could be done both cost-effectively and fairly quickly—within a few years if not months, given the funding’s in place.

References:

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2004. “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg” from People, place, and space reader. [Gieseking et al] Routledge, New York

- Sorkin, Michael. 1999. “Traffic In Democracy” from People, place, and space reader. [Gieseking et al] Routledge, New York

- Images: criticalmass.hu and laestanteriadecho.blogspot.com

- YouTube

Tackling Homelessness in the Smart City

In defining the smart city, we should not limit ourselves to a technology-driven definition. The smart city should be one whose innovation is driven by inventiveness and creativity as well: solving problems not with cameras and touch-screens, but with changes in paradigm, altered perspectives, and updated perceptions. I believe that, rather than thinking of housing in the smart city as advancing the “most advanced” housing experience, it should raise the bar at which we set the lowest level housing experience. Neil Smith makes note that there were only enough beds at the homeless shelter to house one quarter of the homeless people in New York City in 1989; he pairs this with Henry J. Stern’s quote, stating it would be “irresponsible to let the homeless sleep outdoors.” Homelessness is an issue that exists in every major city. The larger a city is, the more visible its homeless population—and not surprisingly, the easier it is to ignore it, look in the opposite direction, dismiss it as just another part of our advanced, 21st-century city. However, if we have any desire to visibly “advance” our cities from a housing standpoint, tackling homelessness would be the place to start.

There’s no question that all cities have a socio-economic hierarchy: there are the rich, there are the middle-class, and there are the poor. This hierarchy exists in every city, country, culture, and time period through history—some people will always have more money than others.

Here’s a little visualization of what that hierarchy looks like, in terms of wealth distribution:

…and here’s what we as Americans think it should be (but that’s a different story altogether):

The most obvious way to observe this is through housing. Some people own mansions. Others own double-wide trailers. Some choose to rent luxurious penthouse apartments; others rent under more humble circumstances (and often with a roommate or two, or three.) Fields states that large cities—New York City in this case—favor weakened rent regulations and increased gentrification because they represent “high profit potential.” (7) The unfortunate truth of the matter is that there are individuals who cannot afford to own OR rent these places to live. The other unfortunate truth is that these individuals are most always unemployed, and often have mental illnesses or disabilities to round out their plight.

Existing solutions are not effective enough for the smart city: nursing homes are expensive, and are difficult to access without a support system; homeless shelters, as alluded to above, are too often crowded and understaffed. They tend to be dangerous as well, making the park bench or brownstone stoop a much more viable place to take up refuge. Thus, the city is “plagued” by homelessness.

A solution to this issue, or at least an aspect of the solution, pairs well with an existing service location in Portland: Preble Street Resource Center. What Preble Street offers is a place that meets the needs of the most at-risk members of the Portland community, offering free meals, life education and counseling, etc., ultimately acting as the support group that these individuals lack otherwise. Of the Preble Street users, an overwhelming number of them are homeless. If Preble Street were paired with the facilities to house 90–100% of these users with modest, safe, temporary housing, we would see an increased success level among at-risk members of society, a decrease in overall city crime, and an overall improved city atmosphere. Essentially, we would be reinventing the halfway house for the 21st-century city.

With the resources and wealth that cities have today, there’s no question that even the largest homeless populations could be housed and given the resources necessary to survive and better integrate back in to society. If we could abolish homelessness in this sense, we would see an instant improvement to the very fabric of the city—an improvement that even IBM’s Rio de Janeiro installation has yet to accomplish.

Sources:

- Smith, Neil. 2014. “Class Struggle on Avenue B,” excerpt from People, Place, and Space Reader. Gieseking, Jen Jack et al. Routledge, New York.

- Fields, Desiree and Uffer, Sabina. 2014. The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin. Urban Studies Journal Foundation.

- [images] 2013. “Wealth Inequality in America” ThinkProgress. http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2011/10/03/334156/top-five-wealthiest-one-percent/

Mental Map Pilot: Duncan J Flynn ’15

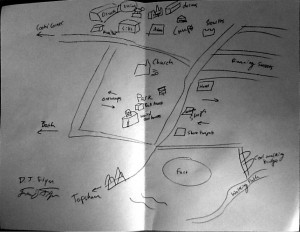

Duncan “DJ” Flynn was the artist behind this map. He is a senior at Bowdoin who also hails from northern Maine. The basis of his inclusions draw upon three main factors: the places where he attends class, the places where he goes running, and the places that he drives to. All of his inclusions are either located on campus or within the area roughly spanning one mile south of the campus. He included many specific locations, including Searles Hall and Fort Andross, which he includes by name. Other spots, such as “running streets” or “shops,” are left more ambiguous but are still nonetheas important to his map. His inclusion of driving routes are also often paired with landmarks, such as the church at the southern corner of campus and the bridge over the Androscoggin River towards Topsham. Noticeably he left out the northern part of campus, citing that “he would have included it but ran out of space on the page.”

Back-to-Basics Approach to the Smart City Public Space

“A park with a garden and a café where you can put flowers and a place to light candles. And have and event there every year.” (Low 169)

This is one of the ideas described by an eighth grader as a plan for public space on the site that previously housed the World Trade Center towers, pre-9/11. The public place is framed as a memorial space, but that small space embodies all of the characteristics of the optimal public space/installation: place to loosely congregate, green space, local and user-friendly business, space of remembrance and celebration, and a space to (annually or spontaneously) assemble and express our rights. Not to speak for the legend himself, but if F. L. Olmstead could have summarized his vision for Central Park in one sentence, this eighth grader’s brief suggestion would have it covered.

I believe that in order to establish a successful, smart-city-oriented public space, the characteristics outlined in the above example represent the key to success. What the green space and flowers suggest is that people enjoy aesthetically pleasing and comforting spaces to visit—and the more pleasing and comforting a space is, the more likely people will stop and stay within the space. This user-spatial relationship is especially apparent in the dichotomy of interactions visible in Bryant Park versus Zucotti Park.

The café represents a positive characteristic for two reasons: first, the business exists at ground level, contributing to the atmosphere of the park as it caters to the users of the park and even extends the boundaries of the park inwards, within the interior space of the cafe; and secondly, the café makes the space marketable. As Low makes apparent, “unless North American urban spaces become commercially successful, their future remains in question.” (164) Investment in the comfort and aesthetics of the park is thus beneficial to the businesses that cater to it, as it ensures continued patronage.

Lastly—and arguably most importantly—is the use of a space for assembly and remembrance. These two characteristics carry a common theme: Americans coming together, in union, for a shared purpose. This is the very root of the public space in all cities, and while the public space held a largely utilitarian purpose in its original conception, the idea behind it was that there needed to be spaces within the labyrinth of the city where people could come together and accomplish a wide variety of civic needs. These needs have not disappeared—they’ve simply changed appearance over time.

Don Mitchell (without coming out and saying it directly) favors the concept of the public space catering to the smart city: “Out of the struggle [over its shape and structure] the city….emerges, and new modes of living, new modes of inhabiting, are invented.” (193) Mitchell’s statement suggests that the public space has held different purposes, different functions, and different draw over time—yet it still remains as an aspect of the city, having diverged little from its original offer.

In terms of implementing this concept in Portland, with smart-city implications, the name of the game is to remain true to what a public space embodies: a place of comfort and aesthetics, a place of congregation and assembly, and simply space in general. Whether future interventions include WiFi hub installations, programmable seating arrangements, or photovoltaic surfaces (to name but a few possibilities) they must keep these key characteristics in mind in order to be successful.

- Mitchell, Don. (2003) “To Go Again To Hyde Park.” Public Space, rights, and social justice. Routledge, New York

- Low, Setha. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” After the world trade center: rethinking new york city. Routledge, New York

Post #2–Small-Scale Intervention

Based on the City Council reports, its apparent that sound infrastructure within Portland is rather lacking, or that it at least needs a fair overhaul. What’s also apparent, however, is that the city council isn’t exactly sure how to go about solving its infrastructure issues, especially those that concern user friendliness. As a primer to a much broader discussion on infrastructure, I’ve detailed a few options that could be potential (and possibly cost-effective) interventions that could benefit Portland in the short and long run:

- Reduction of vehicular access within the Old Port.

- Friendlier pedestrian/bike paths across (on or over) Exchange street.

- Incorporating additional (potentially free-to-park) parking structures.

- Expansion of parks/sidewalks by reducing street width and sidewalk parking spaces.

- interactive information kiosks, scattered throughout the city, that function doubly as free WiFi hotspots.

I listed the information kiosks at the end intentionally, as I believe that this is an existing (though not well-loved) paradigm that could be modified to meet the demands of Portland’s users with a smart-city sort of flare. As Greenfield makes quite apparent, the idea that a smart city should be a perfectly autonomous system is misleading. For one thing, “perfectly autonomous systems” do not exist at the level of complexity on which a city operates. We only need to remember William Whyte’s overhead shot of the park in front of the Seagram Building; hundreds of people walked along unique, intersecting paths within a relatively small space, yet not one person collided with another. From a strictly algorithmic standpoint, the layers of code necessary to achieve such a complex feat with so many independent entities—with a 100% success rate—is utterly absurd. Secondly, such a “perfectly autonomous system” is incredibly unattractive to a city’s residents. Even if such a perfect writ system existed, the mere thought of its implication would likely be shot down. People, especially Americans, value their agency with a unique passion. These kiosks would use the ideas that city residents value personal freedom and that they don’t want their city to operate “perfectly” to its advantage, as it allows the city’s users to access the city at their own will and to whatever extent they determine desirable.

As a smart city application, the traditional idea of a tourist booth wouldn’t apply to these new kiosks. Instead, they would be interactive and multifaceted: while one aspect of the kiosk would maintain the traditional “where-am-I-in-the-city” aspect, it would also provide interactive touch screens that allow access to detailed maps of the city, showing points of interest such as local businesses, public parks, hotels, etc.; one could use a kiosk to look up the various entertainment venues and their respective schedules (and perhaps book a ticket for a film screening or a local play that night); one could look up Duck Fat or DiMillo’s, view a menu, get walking directions, and book a reservation; one could even look up the parking spaces within the city, viewing which parking garages were available/full and their respective fares, or simply finding an empty spot on Congress Street for no-charge parking. Such a kiosk could even act as an ATM, allowing customers to pay for concert tickets, parking fees, and complete various other monetary exchanges right from any convenient location throughout the city.

What really brings this information kiosk out of the 1980s and into smart-city dialogue is its accessibility and agency. These kiosks can be placed in public parks or along well-traveled routes, making them either places to hang out and explore the city options or make predetermined searches/exchanges from a convenient, en route location. Next, the kiosk can function as a free Wi-Fi hub, simultaneously making the kiosks a valued commodity for any flaneur as well as obtaining a city’s dream in a functional and attractive manner (kiosks would not have to look the same either; they could be designed to blend with their surroundings, incorporating like materials and also seamlessly integrating itself into the urban fabric. Finally, the clincher that makes these kiosks accessible is their co-function with a mobile app. The large majority of individuals who own mobile devices will be able to access the kiosk from their own pockets. Not only does the kiosk function as a valuable, in-city informational device, but it also can create a versatile database of all of its greatest assets—which can be shared from any living room, sidewalk, bus stop, or cafe across the country. People in San Diego could book seats at a concert at the State Theater following a business meeting that brings them to Portland; connoisseurs in Portland, Oregon could look up locations to buy gelato in their like-named sister city to sample, compare, and find inspiration for their own recipes. The possibilities are endless, and the agency in encapsulates meshes perfectly with how a city operates.

EzraDC–research interest

Of the three topics of interest, I would be most interested in researching the infrastructure aspect. Portland, Maine, aside from being built on a small tract of land, is also a city that grew rather naturally and without the aid of a dedicated (modern) city planner. Other, more prominent, examples of a similar city design include Boston’s North End and New York City’s Business District on the southern tip of Manhattan. The reason these cities have modern, grid-driven city plans are in direct response to these early districts and their natural city growth patterns. Portland has never quite made a successful transition from natural growth to modern planning. The reason for the drastic planning changes in the larger cities are ultimately resultant of the horrendous infrastructure issues that follow a natural growth pattern. Thus, I want to understand what infrastructural issues Portland contends with–roadways being the main focus, as it is the most prominent of the infrastructural issues, but also looking at water, electrical, and sewage systems, as well as more contemporary systems, like public Wi-Fi/4G access and pedestrian and bicycle transportation systems.

The Townsend lecture was most influential in my choice of infrastructure as my focus topic. The idea of a “smart city” is attractive, especially in an age where most everyone can access all of the world’s information from a rectangular tablet they carry in their front pocket. However, not every city can have an IBM mission control center to monitor and connect its citizens. I want to better understand how this smart city concept can apply to cities that aren’t Rio-sized, as well as how a city’s existing infrastructure affects potential interventions of this nature. Portland is not big; Portland is not rich. But, that said, most cities in the US have these exact qualities. Thus, Portland can function as a case study for all small cities and their ability to implement a smart city-style infrastructure.

I have spent some extended time in both Boston and Copenhagen, cities that are both similar and extremely different in their approach on infrastructure. In both cities, I rode the train to get everywhere I needed to go. Portland does not have such an organized public transportation method–and likely won’t have one unless it experiences a drastic change in size and budget. (Even then, being build on a small, steep, narrow hill, such a large public intervention would likely ruin the city before it helped it. However, I want to use this as a framework for my research approach. I want to find Portland’s infrastructural limits. Once it’s limits are understood and accepted, it will make understanding its capabilities all the easier. In order to find out what Portland can do in the future, one must first find out what it definitely cannot do. Boston and Copenhagen will not have intervention plans that Portland will be able to model, but they do offer two successful plans from which we can draw in finding Portland’s limits.

Infrastructure is wide ranging. Odds are, it will intersect greatly with both housing and public space, so working together with these groups will likely work to all of our advantages.