[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Final-paper.pdf”]

All posts by jwatt

Final Project Proposal

I will be focusing on gentrification in Munjoy Hill and the adoption of Maine iconography, such as lobster buoys and Adirondack chairs, as an indicator of gentrification. In my mapping, I will be layering locations of such motifs on a specific path of Munjoy Hill with data provided from the city (http://click.portlandmaine.gov/gisportal/ and http://www.socialexplorer.com/) on median incomes, education levels, and median age. I will also compile data from Zillow on property value and rent. I hope to provide these layers of data over a twenty year span to show the process of gentrification since the ‘90s and to predict future trends of gentrification in the neighborhood.

My research will focus on cultural capital in Portland and the adoption of the working class lifestyle as a representation of elitism and gentrification. I will analyze property values on Zillow and compare properties in Munjoy Hill to those in other parts of the city and state to prove that “coastal property values and taxes have risen considerably (Gray 2005) and remain relatively high…. In 2004 median shorefront properties were $650,000 per unit (Colgan 2004), whereas Maine’s median residential home price was $174,000 (Maine Association of Realtors 2009).” 1 I will focus on literature by authors including, but not limited to, Loretta Lees, David Foster Wallace, and Pierre Bourdieu, as well as various class readings focused on gentrification.

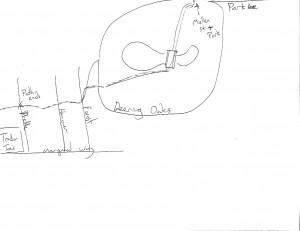

Using data and personal accounts collected from my transect walk, ethnography, and mental maps, I will cite and analyze identifiers of gentrification and cultural capital in Munjoy Hill. I will reference the mental mapper who self-identified as a gentrifier to illustrate that “the boundaries of social and spatial exclusion are clearly visible to longtime residents, even if newcomers are sometimes oblivious of the geography of inequality that divides their neighborhood.” 2 I will contrast this woman’s map with the map of a blue collar worker that I also interviewed in order to provide an account of the varying socioeconomic diversity of Portland. I also hope to incorporate research about the lobster industry and the living standards of lobstermen and women, possibly through communication with the Gulf of Maine Research Institute or the Maine Lobsterman’s Association.

For my technological component, I will propose an app that marks and maps gentrification indicators, such as lobster iconography or Adirondack chairs, throughout the city. This app would rely on crowd sourcing and input by citizens, similar to data collection studies implemented in Seattle and New York. This app could also be combined with other class focuses, such as graffiti or public art, to indicate areas with or without wealth.

From my research, I will propose a form of rent stabilization in Portland based on rent regulation models in New York City. This proposal will help prevent rapid neighborhood turnover, enabling residents to stay in Munjoy Hill for a longer period of time. Ultimately, this will create a more socioeconomically diverse population that is more invested in their neighborhood. Rent stabilization could provide renters with more capital that could then be invested in the city in other ways, such as infrastructure or public space improvements. To capitalize on this capital, a higher tax could be added to benefit neighborhood improvements. By stabilizing rents and then increasing taxes, renters would not feel an economic burden, and their taxes could be invested in public improvements within their neighborhoods.

1 R.S. Steneck et al., “Creation of a Gilded Trap by the High Economic Value of the Maine Lobster Fishery” in Conservation Biology 25, no. 5 (Society for Conservation Biology, 2011): 908.

2 Catlin Cahill, “‘At Risk’? The Fed Up Honeys Re-present the Gentrification of the Lower East Side” in WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 34, no. 1 & 2 (Catlin Cahill, 2006): 343.

Quaint Café to Peppy Ice Cream Shop: An Ethnography and a Wide Range of Mental Cartographers

I walked into Hilltop Café on a Saturday night in late October, not expecting to encounter many Portlanders and expecting to have to hunt around the city during my limited hours to try and find mental maps. I was proven wrong, however, as the café stayed full from the time I entered around a quarter to six until closing time at seven. Unfortunately, the café closed before I could spend a full three hours people watching, but it was neat to observe the emptying and closing of the small café. I went into the city with four friends, and the café was too full for them to sit with me. They ordered drinks while I sat down to start my observations, and they were at the counter for about ten minutes. I later learned that there was a money mix-up, and the barista thought that my friends were trying to cheat her of $20. I observed this interaction, but did not overhear it all and was thus surprised to hear about this little miff at an otherwise quaint café.

The first couple that I talked to in the café were Munjoy Hill residents, but they had only lived in Portland for slightly over two months. The next three people that I talked to in the café, however, all lived in Munjoy Hill and were able to provide insight into my particular focus research field. All three interviewees expressed a desire for improved public transportation, including bus schedules posted at each bus stops, apps to tell you bus schedules (one woman said this would be helpful for her kids who take city buses to school), wifi for public buses, and greater frequency of buses to shorten the commute within the city. This was a very clear consensus that could be greatly improved by the implementation of a myriad of smart technology.

The second woman that I interviewed in the café has been a resident of Munjoy Hill for 15 years. She appeared slightly uncomfortable when I asked her about gentrification in the neighborhood, and she proceeded to identify as a gentrifier, making it seem like there was a stigma around gentrification. She explained that when she first moved to Munjoy Hill and bought her house for $99,000, her friends questioned why she would want to live in a seedy part of the city. Now she and her husband own and have refurbished another property which they rent out. She told me that she has been “priced out” and would not be able to afford her house now.

I found my final interviewee in a peppy ice cream shop in the touristy Old Port, Captain Sam’s Ice Cream. My friends and I entered around 9:00 pm right as this man and his two friends were getting ready to leave. The men were wearing shirts from work, and it seemed as if their shifts had just ended. When I approached the man and asked for a map, he was hesitant at first, and then he agreed. We sat down at a small table by the window and he quickly scribbled down his map. After less than a minute, his friends came over and started razzing him and telling him to quit “doing arts and crafts.” They were clearly ready to go, and although I tried to explain to them that he was helping me out with a research project, they were persistent.

Their buddy got up to go after just about two minutes on the map and they left before I could ask him any questions. It turns out he left his ice cream on the table, so he was back shortly after, but he clearly came back for the ice cream and not my research. This encounter, though limited in the direct information that he provided me, showed an interesting encounter between three working class men and a privileged college student. It seemed as if the men felt uncomfortable in the situation, and I felt uncomfortable as well. It was a surprising environment for the reunion of two different kinds of people, but the limited information the man provided and the context of the encounter nicely supplemented and contrasted the three maps that I collected at the café.

Café ethnography (Hilltop Café):

5:50

-man drawing, twenties, white

-woman on ipod, twenties, white, E. Promenade

-man and woman with coffee, Nalgene, ipad and laptop, hushed voices

-woman with earbuds in couch (runner?)

-older man and woman at table

-two men, 30s, leaving, one with backpack

-woman in 30s-40s, on laptop

-man, younger an and woman, family? Talking

-quiet music

-pretty crowded

-1 barista

6:00

-family (boy, girl man and woman, older man), woman taking photos

-man next to me copying sketch from his phone

-man across with woman and older man balancing phone against vase

-takes about 5 minutes for barista to process order

-man and woman next to me talking at intervals

-barista talking to customers about money (cash mixup?)

-barista giving back money because she trusts them, seems uncomfortable

6:15

-no turnover

-barista in back breaking down cardboard boxes

-woman I interviewed reading fashion magazine

-couple next to me talking again, quietly

6:25

-couple next to me leaving, both have backpacks

6:35

-corner older couple moved out

-man still sketching

-friend with me reading for class

-man with woman and older man looking at phone, still semi-engaged

-family smiling and laughing-man (dad?) with arm around boy (son?)

-family leaving now-lost the 5th older person

-mom scolding daughter for leaving trash on table

-table next to me, 3 tables at other end, 1 chair open

-2nd woman I interviewed getting up to leave, also has backpack

6:40

-barista asks to clear 1st-interviewees dishes

-asks to bring artist paper cup for tea-asks when they close, she responds 7, she wants to do dishes I think

-outlet behind me

6:45

-first interviewee leaves

-friend leaves

-barista walking around cleaning up

-man at the bar, talking to barista

6:50

-woman walks in, asks how long they’re open-doesn’t want to impose

-barista is friendly to her

-woman is probably 20s-30s, earring

-woman leaves after about 5 minutes

6:55

-barista announces closing in 5 minutes

-man walks in a few minutes before closing, urban outfitters bag

-talks to barista-probably friends

-man, woman, older man (family I think) get up to leave, only woman has messenger bag

-woman in seat packs up , laptop plugged in behind seat (takes a few minutes to pack up)-backpack and tote back w/ laptop, holding keys

-man who just walked in sits down across at table, takes off hat

-barista takes trash to back

-barista jokingly puts trash bag on friend

-barista talking about foam levels on capuccions-mentions coffe by design

7:10

-artist leaves

-I leave

-barista’s friend is still sitting at table

-barista is cleaning up

Mental Maps:

Adirondacks and Maine Motifs on Munjoy Hill

I did my transect walk in the Munjoy Hill neighborhood, outlining with Eastern Promenade and wandering through several side streets within the area. My initial focus was going to be the presence of Maine lobster iconography, such as buoys, lobster traps, and other lobster motifs. Only a few minutes into my walk, however, I quickly changed my focus as I began to observe the omnipresence of Adirondack chairs. I adopted an Adirondack radar and identified numerous houses with them across Munjoy Hill. I also observed a few lobster buoys strung on fences and some other Maine motifs, such as seagull weather vanes.

Along Eastern Promenade, in particular, there were stretches where every single house had at least one Adirondack. On this street, all of the chairs faced towards the water and had unobstructed views, often from second or third stories. I am sure that I overlooked many chairs that were on higher levels or hidden from sight, and I did not walk through many of the smaller streets within Munjoy Hill.

With this data, I will compare real estate values to houses that have Adirondack chairs and try to determine if there is a correlation between higher property values, Maine iconography, and gentrified neighborhoods. I could already start to see a correlation through my time spent in the neighborhood and through looking at the area on Zillow. While Adirondack chairs and cultural gentrification do not go hand-in-hand with smart technology and improvements, hopefully my data will reveal clear boundaries between gentrified and non-gentrified areas. With these findings, I would like to explore the integration of low-income housing into these gentrified areas and a more seamless adoption of Maine culture in Munjoy Hill, one that is universal through the area and not only indicative of wealth and property turnover.

- Started on Eastern Promenade and Congress Street

- Many houses along Eastern Promenade had porches on multiple levels (many multi-family homes)

- 236 Promenade Place, a new development on Eastern Promenade, had Adirondacks in the side yard.

- 270 East Promenade had 5 Adirondacks on the front facing the water. There were three large chairs and two smaller ones for kids, and the order of the chairs was different from the order seen on the 2013 Google Street View, although the chairs remained in the same location.

- 288 East Promenade was a newer construction with a stone wall around the house. On the wall was an inscription that read “Friends forever we will be whether walking on the beach or sailing the sea.” Kids were playing in the driveway of this house. (This house does not appear on Google Earth or on Zillow, so either I marked the address wrong or it is very recent construction.)

- 294 Eastern Promenade had two red Adirondacks on the 2nd floor porch.

- There was an older development of apartments at 304 Eastern Promenade called MacArthur Gardens. There were 7 two-story brick multi-family units.

- In front of this development was a cupcake truck at a bike race centered on the grassy park along the water. Most of the people I spoke to watching the race were not Portland residents. One family was from Yarmouth and another family was from Topsham.

- Willis Street had smaller, more run-down houses.

- 41 Montreal Street had a lobster trap in the side yard, but the house did not have other evidence that it was owned by a fishing family. Work was being done on the house.

- Montreal Street seemed to have many families as I observed several bikes and scooters and a kid’s chalkboard on the front porch of a house.

- 102 and 104 North Street had some never developments

- 115 North Street and upwards had several multi-family developments. All of the units were attached and each front porch had two doors, so there were probably two units per porch. Several porches had one side decorated for Halloween and the other side completely bare, suggesting that many of the units were families while others were not.

- Sheridan Street had several 4-story new developments sandwiching older 2 story houses.

- 135 Sheridan Street, a new higher-end development, had very little character and did not fit in well with the surrounding older houses with more charm.

- 99 Sheridan Street had lobster buoys on the side of the house.

- 62 Cumberland Avenue, a newer construction, had Adirondacks on the 1st floor porch. The building also had solar panels on the roof.

- 70 Waterville Street had several lobster buoys on the side of the house.

- Most of the houses on Waterville Street were wooden, but at 64 and 66 Waterville, there were two similar brick houses that stood out from the rest.

- 62 St. Lawrence St. had Adirondacks in the backyard. The house was for sale. The images on Zilllow for one of the units includes pictures of the back patio and a specific shot of one of the Adirondacks.

- 72 St. Lawrence St. had a red Adirondack on the back porch.

- 44 and 46 St. Lawrence St. (two unit house) had a blue Adirondack on the side porch.

- Many of the houses along St. Lawrence Street had rooftop decks.

- 11 St. Lawrence Street was a very modern construction for sale. A unit is listed for just over one million on Zillow.

- 1 St. Lawrence Street had buoys on the side of the house.

- The south side of East Promenade had very fancy old mansions, many of which appeared to be single-family residences.

- 22 Eastern Promenade had a seagull weather vane on the back portion of the house.

- 28 Eastern Promenade had bright Adirondacks on the front porch and older white ones on the side.

- 12 O’Brion Street, a four-family unit, had an Adirondack on the back porch.

- 46 East Promenade had green Adirondacks on the front porch.

- 84 East Promenade (most likely a multi-family unit, based on Zillow sales) had 4 colorful Adirondacks on the side.

- 102 East Promenade (a seven-family unit) had 2 bright pink Adirondacks on the 2nd floor.

- 140 Eastern Promenade had a seagull weather vane.

- 160 Eastern Promenade had 2 colorful Adirondacks and a bright table in between the chairs. This house was not as fancy as its neighbors.

- 168 Eastern Promenade (3 floor multi-family unit) had 2 bright pink Adirondacks and a wicker table.

- 172 Eastern Promenade had sets of Adirondacks on both sides of the house. This house looked newer than its neighbors.

- 182 Eastern Promenade had an Adirondack a small statue of a lighthouse in its side yard.

- 188 Eastern Promenade had 2 Adirondacks in its side yard.

- 25 Congress St. had an Adirondack on its upper side porch.

Residential and Tourist Infrastructure

Portland is rapidly expanding and urbanizing, growing both in its residential and tourist area. In both respects, Portland is still developing and is not on as large of a scale as New York City, so it neither possesses nor requires such large scale infrastructure. However, infrastructural improvements in both a literal and open source sense could satisfy the city’s growing physical needs and enhance its efficiency and technological capabilities.

Cities constantly seek to function more efficiently and “modern city planning is structured around an armature of such conflict avoidance.” [1] While Portland does not attract a large enough volume of traffic to recreate New York traffic patterns, efficiency is still central to the city’s plan for commuters and visitors in and out of the city. Many of Portland’s residential areas are set up in the Jeffersonian grid (see the West End and Munjoy Hill https://www.google.com/maps/place/Portland,+ME/@43.6582817,-70.2627314,3397m/data=!3m1!1e3!4m2!3m1!1s0x4cb29c72aab0ee2d:0x7e9db6b53372fa29“) and from my experience traffic flows well through the busier downtown areas. One recommendation for Portland would be more paths for walkers and cyclists, either designated bike lanes (which the city seems to lack from a quick Google Earth scan) or elevated pathways. Such pedestrian infrastructure would satisfy the hierarchy of “elevated highways, pedestrian skyways…and other movement technologies…for the sake of efficient flow,” [2] which Sorkin argues is necessary to promote urban efficiency and cohesion.

Open source infrastructure could manifest itself in resident-managed community gardens, and new public spaces crafted by citizens themselves would promote residents’ own needs. As Jiménez writes, “such interventions in the urban fabric are transforming, and even directly challenging, the public qualities of urban space.” [3] As Portland continues to be affected by urbanization, it figures that the city’s new populations would want to have a say in the development of their urban space, much like the residents of El Campo experiment.

In terms of its tourist infrastructure, Portland has failed to capitalize on its prime location as a waterfront city. With a relatively flat skyline and with few non-working, “touristy” piers, there is not really any infrastructure through which tourists can take advantage of Portland’s spectacular location and vistas. Adding some lookout towers would provide tourists with such vantage points and make Portland’s skyline more interesting and memorable, something that urban planners and residents have been looking for.

In addition to lookouts, other infrastructure such as bridges or boat docks would enable Portland tourists to explore Portland and its neighboring environments. Between downtown Portland and South Portland is a half-mile spit of water which could be spanned with a bridge catered for walkers and cyclists. Tourists could take this path from downtown Portland and, in a matter of minutes, arrive at Bug Light Park or nearby Simonton Cove, a spectacular beach on the Southern Maine Community College campus that I visited during a geology lab last week.

[1] Sorkin, Michael. 2014 [1999]. “Traffic in Democracy.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 411. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[2] Sorkin, Michael. 2014 [1999]. “Traffic in Democracy.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 411. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[3] Jiménez, Alberto Corsín. 2014. “The Right to Infrastructure: a Prototype for Open Source Urbanism.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32 (2): 342.

[4] Farr-Weinfield, Cynthia. “Greater Portland Convention and Visitors Bureau News.” Blogspot. Last modified March 7, 2010. http://cindysphotoquest.blogspot.com/2010/03/greater-portland-convention-and.html.

[5] Templeton, Cory. “Out Here in the Fields.” Portland Daily Photo. Last modified June 27, 2012. http://www.portlanddailyphoto.com/2012_06_01_archive.html.

Smart Housing and Sustainability in the Urbanizing City

Throughout our study of the smart city, it has become evident that smart technology can and should be applicable to all aspects of modern urban life, from how we navigate our sidewalks to when our window shades close. Urbanized and thickly settled cities like New York lend themselves well to smart changes, as do cities such as Songdo which are being built from the ground up without any preexisting society to contend with. Portland, with one foot marching into the modern city and the other firmly planted in its traditional fishing harbor, challenges us to intermingle smart technology while preserving the city’s character and industry. As it undergoes a housing revolution with increased demand and new, hip neighborhoods, the ideal housing in Portland is one that capitalizes on the charm and beauty of the city while also helping the city advance through the implantation of smart technology.

In all cities, both smart and not-so-smart, sustainability is a key component of housing. Appliances and windows are high efficiency, building materials are recyclable, and much of a housing unit’s energy comes from solar panels mounted on its roof. The ideal housing is an “intelligently managed space that maximizes the requirement of the users…while minimizing resources required.” [1] In other words, modern housing seeks to provide all that homeowners need using as little energy and as few resources as possible.

The study completed in the Crowley reading analyzes the effects of citizen actuation on energy reduction in an office space. This idea can be translated to housing where smart technology tracks the average consumption by room in a house and sends alerts to homeowners with abnormalities or energy saving recommendations. As we discussed in class, Twitter may not be the most appropriate media to send these alerts; energy consumption data can instead be displayed in small monitors in houses (think thermostat sized) or could even be sent to the landlord or board of a co-op housing unit. As the Crowley reading mentions, “while embedding sensors into an environment can be relatively cost-effective, the cost of installing actuation systems can be prohibitive.” [2] For this reason, it could be more efficient to install monitors to track energy consumption rather than smart technology that automatically closes your shades or dims lights in a room.

[1] Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. 2014. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, edited by Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre, 379-380. Springer.

[2] Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. 2014. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, edited by Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre, 383. Springer.

[3] Simon Firth, “Building the Energy-Smart Home,” Hewlett Packard Development Co, accessed October 6, 2014, http://www.hpl.hp.com/news/2011/apr-jun/home_energy_manager.html.

[4] “152-156 Sheridan St #1B, Portland, ME 04101,” Zillow, accessed October 6, 2014, http://www.zillow.com/homedetails/152-156-Sheridan-St-1B-Portland-ME-04101/2105266144_zpid/.

[5] Smith, Neil. 2014 [1996]. “‘Class Struggle on Avenue B’: The Lower East Side as the Wild Wild West.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 316. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Brunswick Mental Maps: Elina ’16

Striking a Balance in Public Space

Public space, a seemingly innocent concept, is one of the most contentious issues in urban planning. Intended as a place for a nice stroll, somewhere to sip your coffee, or an escape from your office cubicle, public space, so we think, is more often than not abused by homeless men, a home for illicit activity, and a playground for angsty teens. In the wake of 9/11, security and safety in public spaces are in a constant battle with how the public can enjoy these spaces and access our rights of public space. As Mitchell succinctly puts it, “public space engenders fears, fears that derive from the sense of public space as uncontrolled space, as a space in which civilization is exceptionally fragile.” [1]

How do we strike a balance between the tamed and the wild, the policed and the terrorized? Although public space in New York City and Portland are vastly different, geographically and demographically, patterns observed in the Big Apple can still be relevant in midcoast Maine. In order to deal with the unruliness that these parks develop, both in terms of landscaping and its inhabitants, many public spaces have become privatized. Through this kind of business, parks receive the money and upkeep that cities often are unable to provide. Bryant Square Park in New York City has used this privatization to increase their “smart” factor, utilizing the space for concerts, movie nights, and skating rinks. However, natural qualities and park autonomy are compromised by advertisements and other marks of the permeating consumerism influence. In New York, such advertisements may not seem out of place, but in a small city such as Portland, it is hard to imagine advertisements lining the quaint parks and quiet, cobblestoned streets.

The park could also do away with its abominable fence which closes it off from the surrounding streets and perpetuates “the loss of freedom of movement so characteristic of the American way of life.” [4]

[1] Mitchell, Don. 2014 [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 192. New York: Routledge, 2014.

[2] http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-3z51KkF2hGQ/UI3BzbyqcbI/AAAAAAAANQU/8yOZa-ZbhHs/s1600/30_b00be1f06a_o.jpg

[3] http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-Tg9u1b1eNfk/UC5gLQ9rTyI/AAAAAAAAScE/Z62XS7ZDfOM/s1600/Greenway_Fountain_HORIZ.jpg

[4] Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 166. New York: Routledge.

[5] http://mainecampus.bangorpublishing.netdna-cdn.com/files/2011/10/IMG_5563WEB-975×651.jpg

Housing Development and Rooftop Terraces

Five smart city recommendations for Portland’s revamping housing market are:

1. Rooftop gardens

2. Solar panels

3. Energy consumption monitors/infographs

4. Low-income housing in all new developments

5. Glass design and colorful, energy efficient lighting

While all of the aforementioned recommendations would have a significant impact on the sustainability and appeal of Portland, I am choosing to focus on the implementation of rooftop gardens for their ability to contribute to the communal, sustainable, and aesthetic spheres of Portland. As we observed on our tours of Portland, there is a depressing shortage of greenery, and while many of the parks could be revamped with easy landscaping fixes, I believe that rooftop gardens would be the most efficient and productive solutions. These gardens would provide each apartment or condominium complex with greenery, fresh produce, an outdoor area for kids and pets, and panoramic views of a beautiful port city lacking such vantage points.

Many apartments and condos already have private decks and outdoor spaces, but the addition of rooftop terraces would provide residents with a communal space that seems to be lacking throughout much of the city. One of Greenfield’s criticism of smart cities is that overspecification “segregates work…from residential clusters and both of these from a designated cultural complex”[1]. In such complexes, however, there would be no divide between residential and cultural complexes. An ideal terrace space would have a space for kids, dogs, and small vegetable gardens. Strategically placed terraces would also be optimal locations for solar panels, which would be ideal for residential sustainability.

In the minutes from Portland City Council’s Meeting last week, a set of guidelines proposed a little over two years ago delineates a series of requirements for features of residential construction. These guidelines say that “rooftop terraces are encouraged to take advantage of views,”[2] and continue to suggest that “from afar, a variable skyline of roof edges, vertical shafts, and signage create interest.”[3] Many of these guidelines focus on the visible appeal of Portland, a city mostly void of a skyline. High rise or multi-story buildings have the capability of adding to these sky lines, especially if they incorporate modern, glass architecture or elements of historic Portland architectural motifs, as the guidelines also suggest. Rooftop gardens add color to the skyline, and stringing lights on trees or having multicolored lighting can greatly improve the ambiance and aesthetic not only on the terrace but of the whole skyline as well.

[1] Adam Greenfield, Against the Smart City (Amazon Kindle Cloud Reader)

[2] Portland Regular City Council Meeting, September 15, 2014, page 190, http://portlandmaine.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Agenda/09152014-605

[3] Portland Regular City Council Meeting, September 15, 2014, page 188, http://portlandmaine.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Agenda/09152014-605

Gentrification and Its Effects on Portland’s Social Space

Shelter is one of the most basic of human needs, and housing can speak greatly of its inhabitants. Housing speaks not only to socioeconomic background, but also to ethnicity and culture, architectural taste, and the value to which the homeowner places on nearby (or not so nearby) amenities. In a world where we are always told not to judge a book by its cover, it is almost impossible to pass by a house without passing judgments about the building itself or who we assume to inhabit it. In a city, especially, the vast range of housing provides tremendous insight into who lives behind the walls.

I am interested in researching housing, and in particular how gentrification affects not only those living in or forced out of a home, but also the culture of the city as a whole. Architecture has always been fascinating to me, and I am an avid viewer of many HGTV (Home and Garden TV) house hunting and renovation shows. In my hometown of Boston, I am always amazed by the multi-million dollar renovations of old buildings, and equally amazed by the displacement of the lower-class people that used to call that swanky new condo home. My mother is a public policy advocate for a homeless shelter for low-income women in Boston, so issues of poverty and low-income housing have always been on the forefront of my family’s and my political agendas.

Portland, like any up-and-coming city, is becoming a more desirable place to live, and realty prices are skyrocketing. As neighborhoods begin to change in price and cultural makeup, I am curious as to how that affects the longtime residents. I want to research where the fishermen and other laborers of the port live, and I am interested to see their perceptions of how this emergence of a hip, foodie city is affecting their industry and way of life. One of Lefebvre’s quotes in the Hayden article spoke to me about this subject: “‘Every society in history has shaped a distinctive social space that meets its intertwined requirements for economic production and social reproduction’”(19). This intertwined economy and society that Lefebvre speaks of is changing in Portland, with the economy being the fixed variable and society being the changing one, and I want to see how that change is affecting the “social space” as a whole.

The “inequality of access to the city” (27) as evidenced by the drastic difference in the size of predominately black and white neighborhoods from Hayden’s study of mental maps encourages me to try similar tactics. Mental maps from Portland’s residents can provide an accurate image (literally) of their perceptions of the city. I would like to find a way to use mental maps of Portland to show the effect of gentrification on the city’s society and economy. I am looking forward to trying a completely new kind of research, and I look forward to being in the midst of this city’s very exciting development.