[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Final-Paper-Reinhardt.docx”]

All posts by kreinhar

Post 7: Following Bus Route 1 in the East End

For my group’s transect walk, we decided to follow Bus Route 1 in the East End to get a better sense of the public bus system in practice. Starting along Congress Street and walking up Munjoy Hill to the East End, we followed the route counter-clockwise eventually returning to our original position at the bottom of Munjoy Hill on Congress Street. This direction is important to note because I believe we went in the opposite direction of the buses. Because we did not follow the same direction and also were only one particular side of the street during the walk, I do wonder how many bus stops we may have missed on our transect walk. This is something to consider when analyzing our observations in the future. The details of the walk are posted below.

Transect Walk

We began at the intersection of Congress and Mountfort heading east on Congress. I noticed that this portion of Congress has a bike lane heading out of Downtown Portland into the East End. The first bus stop we encounter is in front of 206 Congress Street and is displayed with the following sign:

All but one of the other bus stops we encounter are represented simply by this sign. (The two white lines in the image also make up the bike lane I mentioned). The next bus stop is at the intersection of Sheridan and Congress (and is not shown in Google Maps – see the next image where there is no bus icon indicating a stop at this intersection).

The divergence between our observations and some of the stops that are shown on Google Maps already makes me questions Google Maps’ accuracy (or perhaps my own ability to record the location of bus stops).

Anyway, the next stop we observed was on Atlantic Street (the bus route turns to the right on this street) at the corner of Atlantic and Monument. I notice that there is no one else walking on the street with us while we are on Atlantic and the street is lined with parked cars. The next bus stop is at 27 Atlantic Street. We then turn left on the Eastern Promenade and see a bus heading opposite our direction and on to Atlantic Street confirming that these buses do in fact exist. The next bus stop is at the corner of Vesper and the Eastern Promenade. And the next two are at 126 Eastern Promenade and 182 Eastern Promenade. We all notice how beautiful the houses are in this area and how most have an ocean view.

Many of them appear to be broken down into apartments. The next bus stop we see is at Turner and Eastern Promenade and then at 310 Eastern Promenade. We eventually get to the part of the promenade that leads up to the East End Community School. After passing tennis courts to our right, we reach a baseball field and the area unfortunately smells like sewage. We round the corner to the left and circle the school and come to a bus stop in front of the school.

It is the only bus stop we encounter that has a small shelter and map of the bus system. We continue down North Street and encounter bus stops at 143 North Street, Quebec and North, and Cumberland and North. We finish our transect walk when North Street intersects with Congress and we reach area that we have already covered.

Reflection

Admittedly, nothing too paramount devolved from my transect walk, but I did have notice a few important things. I did not expect the bus stop signs to be too significantly obvious on the street, but I was surprised that only one stop had a shelter. It was also comforting to indeed see a bus while on our transect walk. Stops were so frequent that I don’t actually think they are an issue at all. I actually think they are spread too thin and that there should be another major bus stop somewhere at the top of Munjoy Hill or near the Eastern Promenade (like the structure in front of the school) and that would suffice for the entire East End community. This could streamline the bus routes and allow for buses to more frequently come to the area. And following upon my maps and café ethnography, adding GPS and Wi-Fi to the buses could vastly increase ridership as well and is another way the bus system could be improved. Finally, one last impression I had was the lack of bikes or bike racks I noticed in the area. The only evidence of cycling was the one bike lane on Congress Street. It seems like Portland is not much of a bike city at all. Thus, I should also carefully consider the bike sharing ideas I was told by one of my mental mappers as another way to improve transportation as well.

Post 6: Wi-Fi and Transportation Needs as Expressed by Residents of Portland

Reflection on Mental Maps and Café Ethnography

Gathering the mental maps and conducting the café ethnography mostly confirm many of the suspicions I had about the ways some residents of Portland use cafés and view the city. What I found most rewarding were the suggestions for smart technologies I prompted the mental mappers to give after finishing their drawings. Some of their smart city suggestions lined up with my own, so it was nice to have some confirmation of my ideas. The other ideas were valuable in their naturalness as they were fresh ideas coming directly from our population of interest.

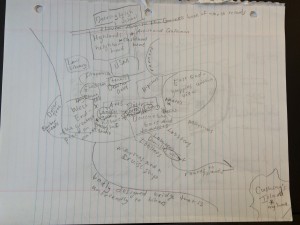

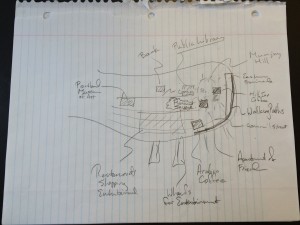

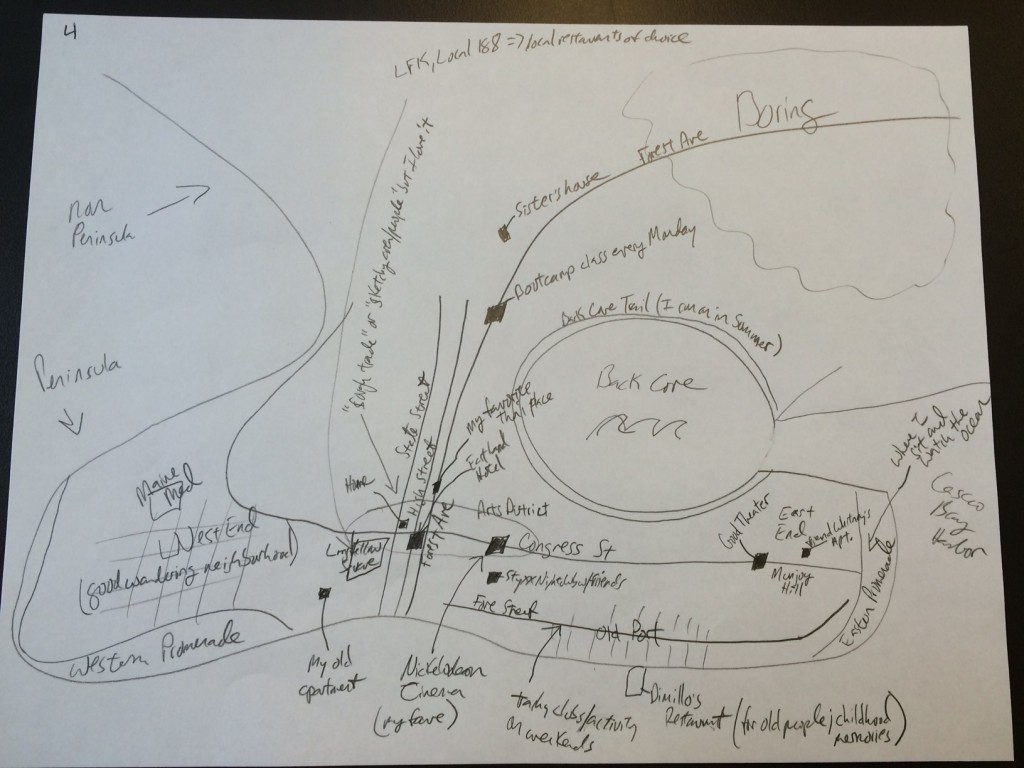

The mental maps demonstrated very different views of Portland, which was not surprising considering that I collected maps from people of many different backgrounds. The first person I collected a map from had spent far more time living in Portland than the others and I saw this in her map through her brutally honest descriptions of neighborhoods (e.g. Old Port = “douchebag bars and tourists”). The participants with less experience living in the city, seemed to provide less social commentary. Those who had the least amount of experience also seemed to have most difficulty drawing a detailed map which makes sense as well. I did find all of their smart city technology suggestions to be very helpful. Wi-Fi and the bus system were both technologies I was concerned about and these both came up. I also found the bike sharing suggestion to be particularly helpful and this is something I will definitely consider.

The café ethnography revealed a strong need for Wi-Fi as well. Most of the people in our café (including all of us) were on a computer or smartphone and requested the Wi-Fi password at some point while we were there. It appeared that many of the people who choose to drink their coffee in the café, did so while also using a computer or some device that can connected to the internet. It should be noted that not everyone in the café who sat down alone went on their computer or phone, and not everyone who were not alone were not on their computer (e.g. there we some people on computers working together too). Also, there were many people who came in to get a coffee to go and left and therefore never required a Wi-Fi password (though I feel that they likely left because there were not seats). Thus, I feel that there is a strong demand for places to go to be on your computer and connect to Wi-Fi outside your home that stretch beyond the public library. We had actually ventured to the Speckled Ax café after encountering two cafés that did not have any room to seat us. This high demand for space in cafés could be attributed to the fact that we visited on a Sunday, but I feel it is likely a common phenomenon.

Following these experiences, I will focus more on public Wi-Fi and the bus system, and also more thoroughly consider biking as a method of transportation in the city in my research. These three smart city recommendations seems to be some of the most important and have all been expressed as a concerned by residents of the city of Portland. For now, I am just intrigued by how simple these recommendations seem considering my own privilege as a Bowdoin student. Free, public Wi-Fi and transportation (e.g. Saferide) are simply given to us as Bowdoin students and we are very fortunate in the respect. However, we should be wary of seeing our own community as a utopia in these respects and should be careful to not project any “Bowdoin” solutions directly on to the city of Portland because of how much these two communities differ despite geographic proximity.

Mental maps

Person 1: Woman, 31, works 3 part-time jobs, has lived in Portland for most of her life and now lives in the West End. Suggests a bike sharing similar to the one in Copenhagen for Portland.

Person 2: Man, 56, spends 2 out of 12 months a year in Portland for many of the past years (actually lives in Mass, but I cam going to consider him my commuter), works in energy and telecom consulting, lives in the East End when he is here, did not really have a smart city suggestions but did express many concerns about the homeless population in Portland.

Person 3: Women, 23, student at SMCC, works in manufacturing, has lived in Portland for nearly 3 years (came to Portland from Rwanda), suggests better announcement of stops on bus to let riders know where there are (perhaps give the bus GPS and a map on the bus can let riders know exactly where they are currently).

Person 4: Man, 31, works at Bowdoin College, has lived in Portland for 2 and a half years, lives at the intersection of Parkside, the West End, and the Arts District, and suggests that Wi-Fi should be accessible to the entire city (not necessarily free, but easily accessible).

Full Ethnography

Speckled Ax Café is located on Congress Street not far from the Maine State Theatre and also near the MECA campus. Went on Sunday October 19, 2014

1:00 – Almost everyone on the café is on a computer or reading. I am here with Alex and Rachel. There is a couple talking quietly in the front. And also two 30ish looking women on their macbooks (with yellow and orange cases) talking to each other every once in a while. A hipster looking young man is reading intensely and another hipster young woman is switching from reading and typing on her macbook.

1:05 – Another hipster looking young man is sitting along and reading and wearing yellow converses. Some other people have come in and are getting coffee to go.

1:10 – The young women on the macbooks have stopped talking and are now both on their computers. Every in this café who has a computer has a macbook.

1:15 – The only sounds are of the occasional people walking in to get coffee to go, the sound of the espresso and coffee machines, and the mood music (mostly indie) playing in the café. The song I have recognized so far is a Beach House song. An older couple (~50) walked in as well. The young man reading intensely gets up to leave and Alex and I move to take his spot because it is a better seat.

1:20 – Alex asks to put her charger in an outlet near the 30ish women on the yellow and orange covered macbooks. They just talked about semesters so I suspect they are college students actually and just look much older than I thought. I also just noticed there are a few people sitting outside as well (even though its 50 degrees out today)

1:25 – 5 people all wearing flannels and knitted hats just walked in. They could not look more Portland. None of them are wearing sneakers, and all have neutral colored shoes. One of them asked the barista of the chocolate is dairy free.

1:30 – A new barista with really long hair has started working and he is making drinks for a couple of 30ish looking people in sweatshirts, Levi’s, and vans.

1:35 – A rock song is playing but otherwise it is very peaceful and quiet.

1:40 – A woman cam in by herself and is not sitting at a small table waiting for her coffee. She is wearing black boots and jeans and a navy jacket and also looks Hispanic and might be one of the first non-white people to come into the café.

1:45 – The young couple that was sitting in the front finally get up to leave. Another indie rock song plays that I don’t know but this one is especially grungy.

1:50 – I notice that the people who were outside have left and the store across the street says Vinyl and Vintage in big letters in its store window.

1:55 – A 40ish looking couple holding a Reny’s bag gets a coffee to go. An old man sits at the place in the front that was empty.

2:00 – I go to the bathroom in the back and there seems to be a lot of people trying to get coffee in the café now.

2:05 – A mellow rock songs has been playing for minutes now and the hipster looking girl who was reading and on her computer near us gets up and leaves. A man in a life is good shirt jeans and a black hat sits next to us at the table and is drawing or writing something on the pad

2:10 – The man next to me gets his coffee from the barista with the long hair. A young women with big glasses and nice boots come in to get a coffee to go and is accompanied by a man with a beard and a gray sweater.

2:15 – The potentially Hispanic woman is still sitting crouched a table looking at her phone and young woman with backpack walks in. She says there are no open tables and immediately turns around and walks out.

2:20 – The women with the orange and yellow macbooks get up to leave and put on Patagonia jackets. The manager of the café opens the door to let some air in and it gets a lot colder in the café.

2:25 – A young man in hiking boots, a sweater, and wearing headphones walks in to order a coffee. Almost everyone at the café is reading except for one couple that are talking quietly at one of the small tables. The man who was reading at the bar gets up to leave and the man with the headphones takes his spot.

2:30 – The Gaslight Anthem’s song “Old White Lincoln” plays and no one is talking except for the one couple. A couple walks in wearing blue and black patagonias and orders coffee.

2:35 – I decide to ask the woman sitting in the front on her computer if she would be willing to draw a map.

3:00 – I sit down again and very few of the other people in the café have left except for the couple that were talking at the small table.

3:05 – semi-charmed kind of life is playing. the guys with the headphones gets up to leave. I wonder how much money the café makes because people usually buy on drink then get up and leave after an hour.

3:10 – The blue Patagonia couple are still talking nearby. The music has become much less indie and more 90s and early 2000s throwbacks instead.

3:15 – The managers friends walk in and they talk near the ordering bar for a while. They eventually leave. Everyone is reading or on a computer except for the one couple talking.

3:20 – The patagonia blue couple continue chatting in the corner at the table where yellow and orange macbooks once were. The man is wearing the blue Patagonia and the woman is wearing a black coat that might not actually be a Patagonia I realize. Also they talk about studying so I wonder if they are in college. They also decide to leave finally.

3:25 – A man in a nice button down shirts and glasses comes in and orders a coffee. He chats with the barista as he makes the coffee.

3:30 – we (the three researchers) all leave.

Infrastructure: Top Down and Bottom Up

Admittedly, when first thinking about infrastructure, only roads, transportation, public space, and schools came to my mind. I did not consider even much of how data and information, let alone social cues too make up infrastructure. But as we have read and discussed in class, infrastructure is the physical, technological, and social materials undergirding everyday social life. Social infrastructure is perhaps the most significant because it is the least tangible and thus intertwined in our everyday lives in complex and enigmatic ways. Simone describes how she found that social infrastructure in Johannesburg notably consisted of economic collaboration among marginalized residents. [1] This kind of infrastructure is also noteworthy in the way that it was created from the bottom up. That is, this “conjunction of heterogeneous activities, modes of production, and institutional forms” [1] grew out of both cultural practice and the existing physical infrastructure in the area implying development beginning from within the culture itself. This infrastructural progress could be vastly different than those suggested by the smart city because much smart technology is usually begun from city management then down to the people. I argue that infrastructure of physical and technological kind must be appropriately implemented so as to consider the underlying culture in order to ensure the most successful installment into cities. Social infrastructure, like laws and regulations which already have underlying cultural reason behind them usually, is inherently cultural and so it will in most cases begin from the bottom up and compliment the beliefs of the people.

However, there have been many cases in the past where a top down approach was used to develop infrastructure in cities. One of the first times that such an approach was used on the city of New York was in 1811 when the Jeffersonian grid was implemented for northern Manhattan. The approach was successful at the time because there simply were very few settlers (except maybe Native Americans, but U.S. history marginalizes them anyway) north of the area around the old Dutch colony and thus the implementation of the grid structure had little impact on current people. Conversely, despite the millions of people that then lived in New York a century and a half later, Robert Moses led nearly countless infrastructural projects in the mid-twentieth century that drastically changed the structure of the city. He famously described how to complete these projects that in some ways literally tore up the city, he had to hack his way with a meat ax. Yet, Berman reflects that “Moses was destroying our world, yet he seemed to be work in the name of values that we ourselves embraced” [2] which were principles like progress and modernity. The power invested in him as the city planner allowed him to have such control over the development of the city. Finally, a recent example of the top down approach was described in Sorkin’s article about the shutting down of crosswalks at 50th and 5th by Mayor Guiliani in 1999. [3] In this mindset, pedestrians were an inconvenience to cars and not the other way around. This approach, however, was against the social infrastructure that had developed in the area (which in this case was actually more of a free for all constructed by the movements of tourists). Although the “car is the main means for activating the landscape” [3] in the eyes of Guiliani and Moses, this was not always the case for the way that social structure had developed upon that landscape. In fact, years later, NYC city planners would realize this and begin to shutdown roads to cars in places like Times Square. Thus, though a top down approach can be a successful approach at city planning, it does generally need to consider the preexisting social infrastructure of a city in its implementation.

The other approach to be considered is a bottom up approach in city planning. By bottom up, I mean, that the potential for more physical (or even legal) infrastructure beginning with the already developed social infrastructure of the people. The Johannesburg example described by Simone is a good example because it highlights how “residents experience new forms of solidarity through their participation in makeshift, ephemeral ways of being social.” [1] This illustrates one of the many ways that this infrastructure contributes to the common good. An outsider could certainly view the less technological ways commerce in the city is organized and simply dismiss it as rudimentary, but the interactions are certainly complex in their own way and allow for more personal interaction. Jimenez also describes how open source urbanism is a great way for smart technology to be implemented in a bottom up approach. Developing the term “right to infrastructure” (following from Lefebvre’s “right to the city”), Jimenez focuses on the importance of the ascent of free and open source software [4]. This sort of approach is also novel because it simultaneously gathers and juggles media systems, interfaces, and social relations together to product a produce an infrastructure that also has the right to produce any existing infrastructure and us. [4] When we discussed in class how social infrastructure can be just as durable, apparent, and reinforcing as physical infrastructure, I recalled reading an article about Nathan Pyle’s book of NYC Basic Tips and Etiquette. [5] His book includes many tips about how to navigate city and also describes many of the rules of behavior that is often expected, but not usually policed. And since this book is simply written and created by a New Yorker, it demonstrates a bottom up approach in developing social infrastructure. The article is here and I will try to post some of the images below (in .gif form so click on them to see the movement!):

Ultimately, city planners need to be as culturally relativistic as possible when considering an implementation of new physical and technological infrastructure. For instance, IBM and Amazon developing lobster drones to deliver goods around the city of Portland may not be the most practical idea because residents of the city may have strong negative feelings about the idea (although they admittedly could be positive – I do not think any research has been done on the matter). There are advantages and disadvantages to both kinds of approaches of infrastructure development, and Portland needs to consider how balancing them both. Free and open source software seems like a right to city development and perhaps it is only practical to allow people to do some of the development work. Of course, city government can always hold the final say, so it simply makes sense that city councils could reach out to exactly the people they are trying to please (the people who live in the city).

References

[1] Simone, AbdouMaliq. “People as Infrastructure.” In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, New York: Routledge, 2014. 241-246.

[2] Berman, Marshall. “All that is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity, Verso.” 1983. 287-348

[3] Sorkin, Michael. “Introduction: Traffic in Democracy.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, New York: Routledge, 2014. 411-415.

[4] Jiménez, Alberto Corsín. “The right to infrastructure: a prototype for open source urbanism.” Environment and Planning: Society and Space 32 (2014): 342-362.

[5] Pyle, Nathan. “NYC Basic Tips and Etiquette”. 2014.

Smart Technology in Housing and Gentrification

Housing cannot be discussed without gentrification and that is exactly the issue that looms over the advent of the smart city. Gentrification as a term was first coined by Ruth Glass in 1964 to describe the process of middle class residents moving into lower class neighborhoods and subsequently driving up property values. The causes for gentrification vary by case, but real estate investment is certainly an important factor. Further, private equity real estate investment is exactly what Fields and Uffer identify as an important factor that causes financialization, which ultimately leads to “higher inequalities in housing affordability and stability and rearranged spaces of abandonment and gentrification.” [1] Therefore, we can expect that the investment needed to build the smart city should have similar results to the effects of financializtion in Berlin in New York described by Fields and Uffer. As global financial integration transformed the political economy of housing in both cities, it either furthered gentrification or deterioration depending on the area. In New York, private equity firms “repurposed informality as a leverage to evict ‘illegal subletters’” [1] forcing out lower-income residents who could not afford legal representation in court. In Berlin, a similar process occurred as well, which was that in neighborhoods where housing investors tried to minimize costs and did not focus in housing maintenance, people would often abandon the deteriorating housing: “Households with the resources to secure better housing often left, concentrating low-income households without other options.” [1] I fear that it is likely that smart technology will be only installed in the areas of the city that investors would deem “appropriate” for the technology and thus this would further marginalize or gentrify certain areas.

The technology necessary to making housing smarter also has its pro and cons as well. A smart city requires housing that is integrated community-wide, or at least all updated with current technology. And Greenfield criticizes the smart city in the way that “it pretends to be an objectivity, a unity and a perfect knowledge that are nowhere achievable, even in principle.” [2] This is certainly the case for smart technology that requires citizen actuation, as it may not always be correctly sensing an issue in the grid and requires anthropogenic maintenance. This kind of intermediate technology, though certainly not objective, does seem to be the most affordable and easy to install. Crowley demonstrated how such technology could reduce energy usage in an office building by up to 26% by notifying workers via twitter of items using energy that were not being used by anyone. [3] Further, this technology may be of minimal cost and this easy to implement in a variety of public and private buildings. Thus, use of smaller scale and less expensive technologies could lessen the probability that energy and technology companies would first begin this program in higher income homes and organizations, subsequently expanding differences between income classes. Therefore, this kind of smart city may actually be very useful in promoting the common good in the way that it uses simple measure to reduce energy costs in buildings.

The reason why we must very strongly consider how investment in smart technology in housing could gentrify areas and exacerbate class differences is because this has proven to be a significant issue in the past. Smith highlights how the transformation of the lower east side into the “East Village” is a perfect example of how gentrification created class conflict. Hundreds of homeless people were evicted from Tompkins Square Park in the dead of winter in December 1989 following riots in August the year before as many were angered about the rampant gentrification of the area. [4] This site and area became a symbol of new urbanism being categorized as the urban “frontier”. [4] It would appear that the American tradiation with manifest destiny continued as “real-estate cowboys” sought to take control of the “uncivil” working class and take over this “new” territory from marginalized communities in a romantic, yet dangerous way. [4] It is very easy to see how this could similarly happen in the future as smart city technology becomes increasingly available. “Software Cowboys” could bring forth sensor technology to “civilize” the lack of smart technology in marginalized neighborhoods.

Overall, Portland will need to both take ideas from the smart city and preexisting housing institutions and structures currently available. Use of human actuation systems in building energy use over the high cost of actuation systems can both easily reduce energy usage and thus costs and also help to develop more of a sense of community in these building through the human actuation process. Therefore, implementation of such housing technology seems pragmatic for the community of Portland (especially for a city that spends much money on the heating of buildings during the cold winter). However, these technologies should be implemented in a cautious manner as to not allow already privileged communities develop more advantages and cause oppressed communities to be more at a disadvantage. Specifically, perhaps it would be wise to install such technology in a non-profit like Preble Street that is already looking for easy ways to reduce energy cost.

Ultimately, as smart technology is likely more frequently used in cities around the world, we must carefully consider how these implementations may worsen preexisting social inequalities. If we look at what real estate investment has done to many communities in the past, we need to carefully consider what smart technology may do to these same and similar communities in the future.

References

[1] Fields, Desiree, and Sabina Uffer. “The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin.” Urban Studies July (2014): 1-17.

[2] Greenfield, A. Against the Smart City. 2013.

[3] Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments. Switzerland: Spring International Publishing, 2014. 379-399.

[4] Smith, Neil. “Class Struggle on Avenue B: The Lower East Side as Wild Wild West.” In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, New York: Routledge, 2014. 314-319.

Brunswick Mental Map: Marina ’17

Responsibility and Representation in Public Space

Considering the readings and our discussion in class, it is evident that public space, and the public sphere in general, is at odds with the largely pervasive private sector of capitalistic America. I found that a point in the Mitchell reading when he references Jeremy Waldron (1991) highlights this point: “In a society where all property is private, those who own none…simply cannot be, because they would have no place to be.” [194]1 This emphasizes the importance of owning property as a significant attribute to being an American citizen and how it marginalizes those who do not possess any property. Public space, thus, can provide a space that allows an opportunity for representation for those unable to be represented by simply the private sector and is illustrated when Mitchell writes “In a world defined by private property, then, public space (as the space for representation) takes on exceptional importance.” [194]1 However, admittedly, it may not be the public space that allows for this representation, but rather it is the representation that “both demands space and creates space.” [195]1 Regardless, there is inherent need and importance surrounding public space as it, in many ways, is a vehicle for many basic spatial rights like access, freedom of action, and changes. [17]2 Despite the fact that public spaces are meant to fulfill many key spatial rights, we still found, through our walk through Portland and examples in class, that these spaces may not be indeed used as often as we would think for something that is so necessary by definition.

Thus, considering this foundation, it is evident that in the smart city, public spaces will continue to be at odds with the private worlds that surround them. Whether or not this distinction puts public spaces in a place of power or is oppressed by the private sector, it would certainly be wise for the public (e.g. the City of Portland) to partner up with useful smart city technology providers (e.g. IBM). Such partnerships can certainly be much smaller and still help to make public spaces much more effective. The Bryant Park Corporation is the group we focused on in class because of the way this privatization of a public space has been widely successful. It would seem highly likely that if corporations, especially those near a public space, are allowed some stake in the public space that they would feel somewhat of a responsibility to take care of it because of the investment made. This is certainly something that Portland and other potential smart cities should keep in mind.

Another factor that smart cities and Portland should consider in developing public space is its utility and how people interact in these spaces. I found an interesting article describing how Keith Hampton is building on the findings of William Whyte decades later in understanding how technology is changing the use of public space. [3] This article mentions the Whyte videos we watched in class that concluded that seating is one of the most important factors in developing useful public spaces. Many of the spaces filmed were near Bryant Park and Hampton did some recent filming to compare with those of the past. Hampton found that social interactions, the number of people, and the number of women has increased in public spaces since Whyte’s filming. This was unexpected as many assume that technology (i.e. use of mobile phones) would actually cause use of public space to decrease. Although he mostly considers technology in the article, certainly the Bryant Park Corporation had some to do with the findings.

It still should be noted that by making public spaces private in some ways, we are preventing them from delivering their original purpose: to allow for a space that has the potential to represent anyone. Although partnerships between the public and private can certainly improve public spaces, does this allow for the representation that is theoretically expected of a public space and benefit the common good? Certainly partnerships may seem to move away from an idea for the common good due to their nature, but they do seem to improve the life experiences of so many people in an efficient manner. When considering the World Trade Center Memorial like in Low’s article, I am not sure we would want an important place of remembrance for all Americans to be in any way controlled by a private company. We would allow, however, for some type of public control (e.g. security), while perhaps still granting many rights to spaces like freedom of action. [4] Both the suggestions by the grade schoolers in Low’s article and the actual result (One World Trade Center and the 9/11 memorial) are certainly a mixture of both public and private as 1WTC is partially owned by a real-estate company and many of the grade schoolers suggested options that varied between the two sectors.

References

1. Mitchell, Don. 2014 [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights, and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al, 192-196. New York: Routledge, 2014.

2. Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Micheal Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 163-72. New York: Routledge, 2014

3. http://www.pps.org/blog/technology-brings-people-together-in-public-spaces-after-all/

4. http://abcnews.go.com/US/selfie-911-memorial-teens-story/story?id=24676819

Considering Winter Smart City Technology and a Greenfield Perspective

Considering Winter Smart City Technology and a Greenfield Perspective

After the field trip, I will admit that one major thing that stuck out to me about Portland was how easily walkable it was. I knew that everything was close, but I had never walked from one part of the city to another like that and it made me realize how truly small it is (which yes is obvious and I probably should have connected the dots sooner). Despite this fact, I realize after that I’m sure that walkability is much less utilized during the winter months simply due to the sheer cold that comes along with a Maine winter. Thus, I think that much of the smart city suggestions that we develop should target issues during the winter months. Such possibilities include better public transportation (especially during the winter), development of the use of the Uber app in the Portland area, closed walkways connecting buildings, smartgrid technology to especially help with heating, and finally (though this is not infrastructure related) some kind of winter/ice festival.

However, before we begin to consider implementing such ideas I want to first emphasize some of Greenfield’s most poignant arguments and also acknowledge the importance of understanding the Portland community as it is today. Personally, the arguments that “the smart city pretends to an objectivity, a unity and a perfect knowledge that are nowhere achievable, even in principle” most stuck out to me and is exemplified in this quote: “What about those human behaviors, and they are many, that we may for whatever reason wish to hide, dissemble, disguise or otherwise prevent being disclosed to the surveillant systems all around us? ‘Perfect knowledge,’ by definition, implies either that no such attempts at obfuscation will be made or that any and all such attempts will remain fruitless. Neither one of these circumstances sounds very much like any city I’m familiar with, or, for that matter, would want to be,” 1. I found this striking because it was easy to visualize how smart cities strive for a perfection that they fundamentally cannot reach. If Siemens installed surveillance systems in Portland that could monitor people for whatever reason, there would of course be error in both the system observing the data and we, as humans, trying to analyze it (like the fire station mishap in NYC). Further, I somehow doubt that many residents of Portland would want to have such technology installed for privacy reasons (and there would certainly be a lengthy discussion of it summarized in the Portland City Council meetings). In addition, Greenfield’s point that the Smart City is overspecified also struck me and is illustrated here: “At best, everyday systems will remain frozen at the level of technological capability inscribed in them at the moment of launch, More likely still, they will begin to decay immediately, as the components on which they depend progressively fail over time,” 2. Basically, we need to carefully consider if any smart technology installed could simple become outdated in only a few years. Perhaps the best and most lasting technology would be the kind that was derived from the residents of Portland themselves (or at least start out as an idea of theirs). Their knowledge of the city may be the best data we have. Thus, taking Greenfield’s arguments into account, we need to consider the smart city technology that would be of most interest of the residents of Portland and work from the bottom up (rather than top down as was done in New Songdo, etc.).

And so, I will explain why my suggestions to help make Portland more livable during the winter can be practical and consider their pros and cons from a community perspective. Better public transportation (e.g. buses) would allow lower socioeconomic classes more ability to move around the city during the cold winter months (and a transportation app would be a great way to allow residents to easily access information about it). To better understand the potential for this idea, it would first be wise to investigate why the bus system in Portland is not commonly used and infrequent. Public transportation could just be infeasible because Portland is not a large enough city to support it. Uber would allow for higher socioeconomic classes to be able to travel around the city more easily too (and could easily increase business for bars and restaruants as well). It could also be a practical smaller alternative to public transportation and I should investigate how commonly used (if at all) it is in Portland now. I’m also certain that both of these transportation methods could be helpful for tourism during the summer months. I am not so sure about the practicality of installing covered walkways, but it is something to consider. And I am not sure if the entire city of Portland is using smartgrid technology for its energy, but I did find that Central Maine Power Company (CMP) did recently install 600,00 smart meters in the area. Finally, some type of winter or holiday festival could be a great attraction for residents during the winter (and even attract tourists). Perhaps this event could be advertised on some sort of Portland City events app that could be created and open access and allow any business organization to post events.

Well, after all those ideas I just want to mention two other things I noticed on the tour that are also important and I’m sure other people in the class are thinking about. Surely, to create better use of public space, free public wi-fi should be more accessible (if there is any at all available). Also, more recycling bins would be a practical addition to the city. That is all I will discuss for now, but I am going to end on the point that we need to carefully investigate and understand the community of Portland before we begin to try to suggest and propose smart technology for it. I would predict that many of the problems we might see in the city that are related to infrastructure are likely not a result of the infrastructure itself but are likely underpinned by some type of social issue (e.g. homelessness) that is related to some kind of anthropological idea (e.g. marginalization).

References

1. Greenfield, A. Against the Smart City. 2013. pp 34.

2. Ibid, pp 46.

Unfolding Social Theory within Space and Transportation as a Vehicle for it

Overall, the Hayden reading and Townsend lecture have forced me to begin to think of cities from a more theoretical and academic standpoint that I have never really done before. Common themes within populations like marginalization and structuralism never really appeared so connected to space and place. Marginalization through exclusion to space (e.g. Jim Crow Laws) and the ways that such production of space can be explained through structuralism (e.g. casitas in Harlem1) demonstrate some of the deep ways that our societies are shaped by the spaces around them, whether or not these spaces are anthropogenic or “natural”. I have certainly begun to think more about how place and space can affect society than about how society produces places and spaces. This was most evident in class when we looked at tourist maps of New York City and as much as we can consider how inequalities within the NYC urban community have made some villages more prominent and some more forgotten, but we must also consider how maps created are a reflection and perhaps reinforcement of these socially constructed ideas.

Despite such interest in some of the social theory that can explain the production or use of space, I would have to say that I am most interested in taking part in the infrastructure research group. When drawing my map of Portland, I was most easily able to recall important streets like Franklin and Congress and of course 295 was one of the first things I drew. Thus, it seems like I am interested in transportation and how we could improve that in Portland. Admittedly, I am really interested in how transit could be tied to more cultural ideas and come from a more society based approach (e.g. working transportation from within a city).

That being said, transportation, regardless of how it was developed, can limit people from important aspects of the community in the same way that some groups have been marginalized in the past. For example, the lack of affordable ways to commute into the city could hinder job seekers from pursuing a job there and let only those who can afford a car to take advantage of such opportunities. I am also certainly interested in how other kinds of infrastructure within a city (e.g. telecommunications) can prohibit or provide advantages to certain groups.

Honestly, I am not entirely sure why my own experience of cities has made me interested in this research topic. Perhaps it has been because I have spent so much of my life commuting from suburban Connecticut to New York City and noting the kinds of the people I encounter on MetroNorth Commuter trains and who has reasonable access to this transportation. Essantially. I would just say that I am most interested in this topic out of the three possible topics we have to choose from.

1. Hayden, Dolores. The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.