Productive Learning In Portland High Schools

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Productive-Learning-in-Portland-small.pdf”]

Maine Motifs: A Study of Gentrification and Cultural Capital on Munjoy Hill

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Final-paper.pdf”]

Unaffordable Housing: Preempting Displacement and Preparing Low-Income Renters

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/bmiller_DIOTC_affordable.compressed.pdf”]

Hannah Rafkin

The Digital Image of the City

Professor Jen Jack Gieseking

12/17/14

BoostPortland: Grappling with Homelessness in the Smart City

Research Area

In the United States, national homelessness declined by over 9% from 2007 to 2013. In the state of Maine, homelessness increased by 17% from 2009 to 2013. In the same timespan, homelessness has increased by 70% in the city of Portland, growing at four times the rate of the state. [1] The city is well known for its extensive support infrastructure, particularly Preble Street Resource Center. Preble Street has been extensively hailed for its “housing first” model, in which people are given housing regardless of substance abuse or mental health problems. Despite the excellence of Portland’s resources for the homeless, these centers are overwhelmed. Shelters often have spillover, leaving many people curling up on chairs or on the floor, oftentimes in other facilities. One cold night in 2013, only 272 shelter sleeping spots were available for double the number of people who sought them out. [1]

The Task Force to Develop a Strategic Plan to Prevent & End Homelessness in Portland reported on the demographics of Portland homelessness as of 2012. The average age of a shelter-goer was 40. Nearly 60% faced mental illness, and nearly 38% grappled with drug addiction – 70% reported a combination of the two. At Florence House, Preble Street’s housing unit for chronically homeless women, 66% were victims of abuse, 54% victims of domestic abuse specifically. Seventy one percent of homeless people had been homeless for a month or less. [2] According to a Bangor Daily News article, a third of homeless people in Portland’s shelters are from the city, another third are from other Maine towns, and another third are from out of state. [3]

Policy Controversies

The City Council of Portland discussed extensive plans to address these issues in the same 2012 report. Their goals included “Retooling the Emergency Shelter System, Rapid Rehousing, Increased Case Management, and Report Monitoring.” Specifically this meant creating a centralized and streamlined intake and assessment process, developing additional housing units, increasing rental opportunities, working with landlords to make housing more accessible, adopting and enhancing an ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) case management system, and increasing work and educational opportunities for homeless youth, families, and veterans. [2]

The Portland Chamber of Commerce responded negatively to the task force and the presence of the homeless population more generally, wondering if the city of Portland was “too attractive to the homeless.” [3] The president of the Downtown District said the homeless were “intimidating,” and “hurt [Portland’s] ability to be a tourist destination and also our business.” [4] The Chamber expressed concern that the city was becoming “a disgusting filthy mess.” [3] Mark Swann, director of Preble Street Resource Center, was “deeply saddened and disappointed by…the misguided and mean-spirited comments…Dehumanizing our neighbors struggling with poverty, homelessness and hunger is deplorable.” He advised the Chamber to talk with Preble Street’s councilors to get a better sense of the “attractiveness” of homeless life in Portland. [4]

These contrasting attitudes represent a growing tension in Portland between wealthy gentrification and impoverished homelessness. As homelessness has skyrocketed in recent years, the city has become increasingly trendy – ‘hipster’ cafes, pricey shops, and condos-with-a-view have sprung up incessantly. Swann’s suggestion for conversation between the Chamber and the Resource Center is wise – these seemingly opposing forces could benefit from dialogue instead of distant and impassioned resentment.

I observed this conflict of interests in action during my transect walk through Portland, noticing the strained simultaneity of homelessness and gentrification. I was particularly struck by a juxtaposition I observed at the busy intersection of Franklin Street and Marginal Way. A homeless man stood leaning against a road sign, holding up a flimsy piece of cardboard. Yards away was a store called Planet Dog, catering exclusively to the bedding, food, toys, and accessories of Portland’s canines. An astronomically expensive antique shop and a home entertainment center sat down the road from Preble Street Resource Center.

Later on, another juxtaposition presented itself. I was walking through Congress Square Park taking photographs and surveying the scene. Some people sat on the steps, one man grilled burgers, another played guitar. My taking pictures clearly upset a woman sitting on a bench, who got up and followed me for several blocks, slurring and staggering, yelling “Fuck the white house, bitch” and other obscenities. Nonsensical as the specific expression of her outrage may have been, this encounter was representative of a larger urban tension. I am a white girl from New Jersey, doing coursework for a course at an elite college, wielding an imposing SLR camera in the attempt of ‘capturing the city,’ only visiting for a brief and comfortable afternoon of exploration. In that instance, I was encroaching on her space – she does not have the option to ‘explore’ the city lightheartedly.

Layers of Congress Square Park

Boost Portland – Smart City Solution

A man I interviewed outside of Preble Street said that complications of daily life and a lack of affordable housing make it “impossible for people to get on their feet” in Portland. I propose a combined application, website, and texting service called BoostPortland, aimed to get Portland’s at-risk population on their feet – and to keep them on their feet – by meeting everyday, individualized needs beyond sleep and food. BoostPortland will draw on the city’s own residents, businesses, and organizations to to support the city’s neediest citizens, creating a pervasive network dedicated to bettering their community. BoostPortland will provide a platform for the struggling citizens of Portland to receive help in confronting the myriad challenges of daily life.

Users would create posts, either offering or seeking out assistance. An individual could post offering help with resumes at the public library, advertising an odd job like shoveling a driveway, or giving away clothing items. Somebody could post requesting a ride to a job interview, asking for a winter jacket, or seeking help with English. Businesses could post offering free food, wireless Internet, a space to organize, or perhaps just some time to warm up.

This format allows for direct and impactful volunteerism on the terms of both the giver and the receiver. Specific, attainable needs will be met at a convenient time and a convenient place for both parties, while creating connections between Portlanders of varied backgrounds. Additionally, involving a diverse group of businesses – from Salvation Army to Portland Architechtural Salvage – might help to ground them in the often-grim realities in the city. This might give them a better understanding of the challenges facing the homeless population, and allow for increased awareness of the role of commerce in making Portland an increasingly expensive place to live. Ideally, businesses will then reconsider the sentiments expressed by the Chamber of Commerce in response to the task force.

Approach to the Common Good for the City

Urban centers are hotbeds of diversity. Socioeconomic, racial, cultural, sexual, and lifestyle differences guarantee exposure to fresh perspectives. In a city with a focus on the common good, all perspectives are given a voice, and there exists a platform for productive and engaging “encounter and exchange.” [5] In a city with a focus on the common good, all citizens have access to basic human rights – water, food, and shelter are attainable for everyone. In a city with a focus on the common good, there is a network of organized care and action around issues of social justice impacting the city.

The homelessness task force is on the right track to meeting this definition (though its website’s most recent agenda item is dated October 11, 2012) but the Chamber of Commerce’s focus on business and tourism poses roadblocks in attaining the common good in Portland.

Approach to the Smart City

The ambitious and futuristic proposals to re-envision the technological functioning of the modern day city in “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments” are exciting. [6] But the idea of “everything [becoming] a sensor” is perhaps overzealous, and has major potential to verge into Big Brother territory. [6] The focus on using technology to better conserve energy is very appealing, however.

A truly smart city integrates technologies that are “situated in a specific locale and human context,” as described by Adam Greenfield. [7] South Korea’s city of Songdo exemplifies the pervasiveness of technology described in Crowley, Curry, and Breslin’s article, but lacks contextual concern for the interests, behaviors, and problems facing its citizens. Songdo was built before those interests, behaviors, and problems could even manifest, before city planners could consider how their innovations would function within the specific flow and feel of the city. In the smart city, citizens define the technology; the technology does not define the citizens.

As technologies tend to be expensive, they come with concerns of accessibility. The smart city does not limit its innovations to “those who can afford it and conform to middle-class rules of appearance and conduct.” [8] This notion is particularly pertinent to my research area.

Literature Review

“To Go Again to Hyde Park” by Don Mitchell emphasizes each citizen’s “right to the city,” though those rights are not always made equal in practice. [5] As “some members of society are not covered by any property right,” they must “find a way to inhabit the city…as with squatting, and with the collective movements of the landless, to undermine the power of property and its state sanction, or otherwise appropriate and inhabit the city.” [5] Mitchell advocates for the marginalized populations’ participation – forcefully, if need be – in the dialogue of urban life. In “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space,” Dolores Hayden also stresses the importance of undervalued voices in urban conversation. She discusses the development of the urban landscape, describing the role of every inhabitant of a city, the marginalized included, in shaping its look, feel, and experience: “Indigenous residents as well as colonizers, ditchdiggers as well as architects, migrant workers as well as mayors, housewives as well as housing inspectors, are all active shaping the urban landscape.” [9]

Technology continues to reform the way citizens interact with each other and share ideas, even within disenfranchised populations. The homeless community’s usage of cell phones has skyrocketed in recent years. In 2009, advocates from Washington D.C. estimated that 30%-45% of the homeless population they worked with owned cell phones. [10] In a 2010 study of homeless cell phone use in Philadelphia, 44% of a 100-person sample size owned cell phones. [11] A 2013 study found that 70.7% of Connecticut homeless emergency room patients owned cell phones. [12] No such study exists for Portland, but similar patterns likely apply. As the homeless population becomes increasingly technologically active, a solution like BoostPortland gains potential to foster discussion and exchange between the haves and have-nots of the city, drawing on the broader community to improve the lives of Portland’s neediest citizens.

Integrating technology into such projects must be done thoughtfully, however. At a 2012 technology conference in Austin, Texas, a marketing agency proposed that homeless people be utilized as mobile wireless Internet transmitters. For $20 a day, homeless people walked around wearing shirts that said “I’m _____, A 4G Hotspot.” Instead of creating inclusive dialogue, this “charitable experiment” denied the personhood of the participants, defining individuals only by their potential for beneficial functionality. One blogger aptly described the project as “something out of a darkly satirical science-fiction dystopia.” [13]

The Hack to End Homelessness meet up in Seattle provides a better model for conscientious use of technology – developers, designers, and “do-gooders” got together to brainstorm solutions for homelessness. The event produced exciting data, maps, applications, and other programs with a focus on dialogue between groups with different staked interests – the event organizer foregrounded the importance of “[reducing] tension between the housing community and tech workers.” [14]

Methods

Representing the homeless through maps was a difficult undertaking – without an address, homeless citizens do not get represented in government census data. Data about issues surrounding homelessness exists (housing, income, neighborhoods). Social Explorer median income census data and the ‘PlanNeighborhoods’ Portland Shapefile were particularly helpful in establishing a backdrop for new data about homelessness directly.

I created new data sets on Portland’s homeless encampments, resource centers, and affordable housing. I began by geocoding the addresses of all of the homeless encampments mentioned in the Portland Press Herald in the past three years to get a sense of where the homeless are congregating. Then, I placed these data points on top of median income data to juxtapose the temporary homes of the homeless with the financial context of their temporary surroundings. This layer provides a means of accounting for transient homes of those that the census does not count – an attempt to bring the homeless onto the city map. I also geocoded all of Portland’s resource centers, shelters, and soup kitchens, and placed them on the same map as the encampments to see where help is concentrated in the city and where it is lacking. As the dearth of affordable housing has made living a stable life in Portland increasingly difficult, I was curious about the prevalence and whereabouts of existing affordable housing in the city, so I mapped housing units deemed affordable by the Maine State Housing Authority. [15]

Findings

As the above map demonstrates, the homeless are inclined to camp near the water and in wooded areas. They camp mostly in low- to middle-income regions, though not exclusively. The city’s resource centers are mostly concentrated in a small pocket in Bayside, a low-income region of Portland. The encampments and resource centers do not show significant overlap in location.

The above map shows that housing deemed affordable by the Maine State Housing Authority is centralized in the Downtown, Bayside, and East End regions of Portland. It is interesting and concerning to consider the consequences of sectioning off low-income populations, reminiscent of tenement-style urban layouts that Hayden discusses in “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” [9]

Reflections: Technological Concerns

BoostPortland will have three technological components to support the expected range of socioeconomic backgrounds: a smartphone application, a website, and an SMS texting service. The smartphone application will likely appeal to a more economically stable faction of users, as they are more likely to own them. It will have a simple and clean interface. There will be four tabs: Get Help, a list of the day’s offers, Give Help, a list of the days requests, Map, a map version of both lists, and Post, an interface for users to offer or request assistance. Users can click on an offer or a request for more details, linking to contact information of the poster. The website will be structured identically. The SMS service will allow those with basic cell phones to request or give assistance on the move. Users can text in requests or offers, to be added to the daily lists. Users can also subscribe to a daily text containing one or both lists, and can text in a reply to be put in contact with the giver or receiver of help.

This technology-driven idea of a combined application, website, and texting service – aimed to assist Portland’s most disenfranchised population – comes with obvious challenges. Without such basic amenities as consistent shelter or food, the homeless and impoverished are much less likely than the average Portlander to have access to such technologies. However, homeless people nation-wide are becoming increasingly technologically connected, as shown by the aforementioned studies on homeless cell phone use in Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and Connecticut. With these changes, homeless people will have increasing accessibility to solutions in the form of apps and websites, and especially basic SMS texting. This is particularly true of homeless youth and the recently homeless, as noted by Mark Swann, director of Preble Street. Additionally, Preble Street and the Portland Public Library have free computers where users could access the website component of BoostPortland.

Policy Recommendation

Portland’s homelessness task force has laid out some very important goals. I suggest that the City Council involves the Chamber of Commerce in achieving them to augment the city’s response to homelessness. Getting businesses involved in the issue will give them a broader understanding of what is happening to the marginalized populations in the city. This approach will also give the Council more power and leverage in addressing their goals, while creating productive dialogue between seemingly antagonistic forces, as Hack to End Homelessness sought to do. In light of the Chamber of Commerce’s commentary on the task force and, most likely, reticence to help, the City Council might create an incentive program to draw the Chamber to the Portland’s social justice issues.

Conclusion

BoostPortland foregrounds the voices of those in need by creating a communal network of Portlanders determined to face the growing problem of homelessness. By including local businesses and addressing gentrification head on, it has the potential to bridge the gap between monetary interests and humanitarian interests. I believe that this solution can make Portland a smarter, more connected, and more engaged city.

Works Cited

[1] Billings, Randy. “Homelessness Hits Record High in Portland.” Portland Press Herald. October 27, 2013. http://www.pressherald.com/2013/10/27/homelessness_hits_record_high_in_portland_/.

[2] “Report of the Task Force to Develop a Strategic Plan to Prevent & End Homelessness in Portland.” Portland City Council. November 16, 2012. https://me-portland.civicplus.com/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Item/132?fileID=695.

[3] Koenig, Seth. “Is Portland ‘too attractive’ to homeless people?” Bangor Daily News. December 21, 2012. http://bangordailynews.com/2012/12/21/news/portland/are-cities-like-portland-too-attractive-to-homeless-people/.

[4] Murphy, Edward. “Preble Street Head Decries Chamber Remarks on Homelessness.” Portland Press Herald. November 16, 2012. http://www.pressherald.com/2012/11/16/preble-street-head-decries-chamber-remarks-on-homelessness/.

[5] Mitchell, Don. [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al. New York: Routledge, 2014)

[6] Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. 2014. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, edited by Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre, 379–99. Springer.

[7] Greenfield, Adam. 2013. Against the Smart City. 1.3 edition.

[8] Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Micheal Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 163-72. New York: Routledge, 2014

[9] Hayden, Dolores. 1997. “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” In The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, 14-43. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[10] Dvorak, Petula. “D.C. Homeless People Use Cellphones, Blogs, and E-Mail to Stay on Top of Things.” The Washington Post. March 23, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/22/AR2009032201835.html.

[11] Eyrich-Garg, Karin. “Mobile Phone Technology: A New Paradigm for the Prevention, Treatment, and Research of the Non-sheltered “Street” Homeless?” US National Library of Medicine. April 16, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2871091/.

[12] Eysenbach, Gunther. “New Media Use by Patients Who Are Homeless: The Potential of MHealth to Build Connectivity.” US National Library of Medicine. September 30, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3786002/.

[13] Wortham, Jenna. “Use of Homeless as Internet Hot Spots Backfires on Marketer.” The New York Times. March 12, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/13/technology/homeless-as-wi-fi-transmitters-creates-a-stir-in-austin.html?_r=0.

[14] Soper, Taylor. “Hack to End Homelessness: Maps, Social Networks and Other Ideas to Help Seattle’s Homeless – GeekWire.” GeekWire. May 5, 2014. http://www.geekwire.com/2014/hack-end-homelessness-recap-maps-social-networks-startup-ideas/.

[15] “Cumberland County Affordable Housing Options.” Maine State Housing Authority. December, 2014. http://www.mainehousing.org/docs/default-source/housing-facts—subsidized/cumberlandsubsidizedhousing.pdf?sfvrsn=5.

Optimizing Portland, Maine’s Public Information Access: Coupling Cloud Technology with Physical Kiosks for Seamless Urban Connectivity

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/DIOTC-Final-Paper-web.pdf”]

Amending the Comprehensive Plan: A Study of Portland’s Recreational Infrastructure

Amending the Comprehensive Plan: A Study of Portland’s Recreational Infrastructure

Introduction and Research Question:

Portland, ME is a vibrant, diverse city in an easily accessible location only two hours north of Boston. As a major vacation destination throughout the summer, Portland places great value on its tourism industry. Healthy and vibrant cities must provide residents with proper infrastructure, namely the physical structures that make up the city, to support their and their primary industries. Portland’s infrastructure must support its tourism as well as its significant year-round population, 17.1% of whom are under the age of eighteen. As a substantial percentage of Portland’s population, school-age citizens have certain infrastructural needs that should be met by the city. Portland outlines certain policy goals in the city of Portland’s Comprehensive Plan including one stating that “recreational opportunities should be available for all ages and genders” and that “neighborhood open space should be within walking distance” for all residents. However, playspaces in Portland are not all easily accessible by children and do not serve children in all four seasons. For Portland to successfully meet its own goal of providing playspace infrastructure for its youngest citizens, it needs to provide more playspaces throughout the city, but also playspace infrastructure that is functional in multiple seasons and various weather conditions. I propose that Portland not only expand the number of playspaces in the city, but also create technology-controlled, weather-adaptable playspaces for children to use throughout all four seasons of the year.

Approach to the Common Good:

Residents in cities select a city in which to live for various reasons. However, one thing that all residents in any given city have in common is that together, they make up the living and breathing aspects of that city. Because of their proximity to restaurants, cultural hubs, and downtown areas, city residents often take for granted the variety of services and experiences to which they have access. There seem to be an endless number of perks to living in a city. However, many of these perks and services are expensive, and not all city residents are wealthy. Is a city truly accessible to all and benefitting the common good if it is not giving opportunities to all of its residents? While open park and recreation space is seen as a public good, it is often located in regions not easily accessible by lower socioeconomic classes. Further, playgrounds that do exist in lower-class neighborhoods are often dilapidated, run down, and known as dangerous locations after dark. In these circumstances, how can we create something that is accessible by all and for the common good? In my mind, children have a “right to play” similar to Henri Lefebvre’s “right to the city.” While the idea of creating something for the common good usually refers to the production of something that is entirely inclusive to all populations, children seem to have been vastly underserved in many other aspects of city planning in Portland, and therefore deserve to have something created specifically for them. If Portland as a city lists a policy goal relating to giving more of the population access to park and play space, then Portland needs to provide experiences for all, including the less wealthy and those without a vote: youth.

Approach to the Smart City:

One way in which a city can be characterized as a “smart city” is if aspects of the city are capable of adapting technology to fit the needs of the city. This could come to fruition in many ways. For example, this can be achieved with sensors that trigger changes in functionality of an office building depending on the number of people inside and whether they are working alone or collaboratively. The definition of a smart city varies depending on the goals of the project; they can benefit citizens economically, socially, politically, or culturally. There are also many methods by which a smart city can be created. Certain smart cities are built from the ground up; one example of this is Songdo, a city that is being developed as an “international business district” in South Korea. Other cities can become “smart” over time depending on the integration of technology into pre-existing city life.

I see a smart city as a city that is able to use technology to make itself more accessible to all residents. Portland is a very quaint city in that it fits within a specific New England architectural style, so a mass overhaul of Portland’s architecture to would not only be expensive, but would cause Portland to lose its New England tourism draw. Portland is capable of incorporating technology in other ways in order to benefit all of its citizens. As Margarita Angelidou says in her article “Smart city policies: A spatial approach,” “emphasis should be placed on regenerating degraded urban areas,” rather than just starting from scratch. This is entirely applicable to playspaces in Portland, as Portland’s already existing playgrounds can be redone and new ones can be created in derelict space in order to create technologically advanced, adaptable playgrounds.

Literature Review:

While the idea of a “weather-adaptable” playground is entirely new, the idea of play as a crucial part of a child’s development is supported by a number of national and international organizations. For example, the USA chapter of the International Play Association’s stated purpose is “to protect, preserve, and promote play as a fundamental right for all humans.” Roger Hart, the director of the Children’s Environments Research Group at CUNY, echoes this in an article in which he makes a claim about children’s right to play as a “basic right, fundamental to children’s development” based off of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child was a meeting in 1989 that wrote a document with a number of articles relating to the rights of all children. Article 31 of the document declares that “States Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.” Since then, many researchers have worked tirelessly to stress the importance of play in children’s lives and how to incorporate new ideas of play into playspaces.

A considerable portion of literature on the idea of play is primarily focused on the link between outdoor playtime and its medical benefits, such as a decrease in obesity. More recent research has focused on creating new kinds of playspaces as well. In an article for Parks & Recreation, associate editor Samantha Bartram discusses two important thoughts, the idea of “play deserts,” spaces where there is a lack of playspace, and how fewer than four out of ten Americans live within walking distance of a park. In another article for Parks & Recreation, Steve Casey discusses the redevelopment of a playground in Missouri into an adventure playground. This playground not only incorporates the idea of “free play” into its design, but also happens to be a very environmentally sustainable playground in its construction and function. These articles both highlight the need to create playspace where it lacks and the need to do so in creative and ecologically friendly ways. They reference the ways in which the development of adequate play space is difficult; in certain regions, it does not exist at all, and in others, economic, geographic, social, and visual factors have to be taken into account before the construction of a playground.

While researchers are away of the importance of play in a child’s development, very little research has done about the incorporation of smart technology into playspaces. In my research, I browsed numerous technology websites to look into how playgrounds are currently being designed. My search led me towards three websites in particular, wired.com, gizmodo.com, and nytimes.com. Through these websites, I found numerous contemporary playspace ideas. One article I read on wired.com outlines the creation of a company, Free Play, focused on “creating a series of abstract play structures that will challenge children’s creativity during playtime.” Free Play structures are designed in a way so that children can interact with them how they please, a very new idea compared to a playground containing a typical swing and ladder. Giving children the freedom to interface with playspaces in unique ways allows them a certain level of freedom that does not necessarily exist in a standard playground.

Figure 1: A playspace designed by Free Play, a company focused on bringing imagination-based play to children through unique playspace pieces.

Figure 1: A playspace designed by Free Play, a company focused on bringing imagination-based play to children through unique playspace pieces.

Another article on wired.com outlines a 2010 contest on the website for designing the future of playgrounds and contains images of newfangled playgrounds that could exist in the year 2024. These playgrounds are complete with an autonomous stroller rink, 360º rocket swing, and 10-G merry go round. While these ideas are not currently feasible in terms of safety, cost, and implementation, they speak to the creativity that can go into the construction of playgrounds today.

An article from the New York Times, “Beer for Me, Apple Juice for Her,” outlines a very unique idea of a playspace, the German beer garden, as a space in which parents and children can come together, both indoors and outdoors, to play. In one beer hall in Brooklyn, NY, there is even a “Babies & Bier” playgroup with a $10 entrance fee that includes snacks and drinks (both alcoholic and nonalcoholic). The owner of the Brooklyn beer hall started the playgroups “to address a lack of indoor play spaces” because she found that playspaces options were quite limited in inclement weather. While not exactly smart technology, this is a unique way to incorporate the element of play into less-traditional locations and to acknowledge that play can be encouraged and incorporated into other cultural traditions.

The final article I will discuss is a gizmodo.com article that describes a Danish plan to convert parking garages into multi-functional spaces. By adding open space primarily on top of parking garages, Copenhagen will be able to use otherwise useless space and turn it into parks, workout zones, and gardens for its residents. While this idea is not necessarily weather-proof or adaptable, it is one way in which cities can revamp pre-existing structures into new, more aesthetically pleasing, and functional spaces.

Figure 2: A sketch of what the Copenhagen parking garage playspaces could look like.

Figure 2: A sketch of what the Copenhagen parking garage playspaces could look like.

Methodology:

Over a period of two months, I spent time exploring Portland and observing my surroundings. While at a café in the Arts District, Local Sprouts Cooperative, I realized that there was a significant population of children in Portland that I had not previously noticed. I visited Local Sprouts Cooperative on a cloudy Saturday morning in late October and found the café to be almost entirely populated by parents and their young children. Local Sprouts Cooperative seems to be a very kid-friendly café and even provides space in a corner of the café as a children’s play area. Seeing such a high density of children in a café made me wonder why they were playing there and not outdoors in a playspace. If the weather were accommodating and they play space were close by, might parents have preferred to be there with their kids instead of packed into a café’s children’s corner?

The next portion of my research was spent making observations throughout a neighborhood while on a transect walk. I chose to walk through East Bayside and Munjoy Hill and focused specifically on looking for examples of educational infrastructure. For the purpose of my walk, I wanted to look at where schools and their playgrounds were located among the neighborhoods. Prior to my walk, I made note of where schools were listed on Google Maps so that as I walked by them, I see whether they had playgrounds. Many of the schools listed on my map did not actually exist; further, there were very few playgrounds spread out through the two neighborhoods. While my fieldwork has been limited in locations of Portland as a whole, the lack of playgrounds in the downtown area makes me think that Portland is underserving its youth by not providing them with their “right to play” and their “right to the city.”

Having finished my physical fieldwork in Portland, I turned to my computer for the next portion of my research. Using QGIS Software, I mapped out locations of schools and playgrounds in Portland (Figure 3) to look at where schools were located, where their specific playgrounds were located, and where neighborhood playgrounds were located with respect to schools. Looking at this map, however, I realized that it was not enough to simply map out the locations of schools and playgrounds. While many students are able to go to playgrounds straight from school, students, in my experience, are more likely to play near their homes. For this, I needed to create another map detailing where playgrounds are with respect to where the majority of students live.

Figure 3: Location of Portland schools and playspaces on mainland Portland. Data from City of Portland data sets, kaboom.org.

In order to do this, I mapped data from the US Census against the locations of schools and playgrounds (Figure 4). Using the percentages of residents under 18, I was able to compare where children live in Portland to where schools and playspaces are. The darkest blue portions of the map are the highest percentages of under-18 residents, between 21.8% and 24.4%. The white portions are the lowest percentages of under-18 residents, between 6.21% and 12.22%. On both maps, I chose to omit island portions of Portland, as full census data was not always available and schools and playgrounds were few and far between.

Figure 4: Location of Portland schools and playspaces and percentage of residents under the age of 18. Data from City of Portland data sets, kaboom.org, US Census.

The final element of my research was to look at how playgrounds are being designed and used elsewhere as inspiration for my policy recommendations for Portland. For this, I turned to the internet and looked at a variety of sources, including academic, media, and news sources. Many of these sources were on the development of new, more imagination-inspired playgrounds (such as those mentioned in the Literature Review section); others were on the idea of play as a necessary part of children’s development.

Findings:

When I looked at both of my maps, I found that Figure 3 makes it seem as though there are quite a number of playspaces around Portland near all schools. However, with the addition of the US Census data, it became obvious to me that while there seems to be a larger concentration of playspaces in the downtown area of Portland, there are very few playspaces in regions where children actually live. The darkest blue portions of the map in Figure 4 are not only the regions with the highest portion of under-18 residents, but are also the regions with the fewest playspaces.

My online research led me to numerous playspace ideas that have not been widely developed yet, but sadly did not lead me to any already existing, physically adaptable, weather-proof playspace ideas. While many people are working towards new ideas of playspaces and trying to stay away from a classic model of swing set, ladder, and monkey bars, no one has gone past the imagination playground to create a playground model that is functional in different weather conditions.

Discussion:

My research has led me to the conclusion that Portland not only needs more playgrounds, but also needs weather-adaptable playgrounds so that children might have the ability to play outside throughout all four seasons. I also concluded that Portland is currently failing to provide access to parks or play space as proposed in its Comprehensive Plan. If it is recommended that people have some kind of park or play space within walking distance, or ½ mile, from their home, it is impossible that Portland’s youth have adequate access and ability to get to a park or playground. Portland is not living up to its own policy if it does not add playspaces in the areas of highest under-18 population density.

I propose that Portland expand the number of playspaces predominantly in two areas, in zones where there are too few playspaces and a high density of the under-18 population, and in poverty zones. By placing new playspaces in these areas, they will hopefully be able to accomplish two goals. First, they will support the city’s goals to provide playspaces, and second, they may contribute to the revitalization of impoverished communities. I also believe that creating playspaces on top of already existing buildings such as parking lots (similar to the idea being implemented in Copenhagen) is a viable way to create playspace infrastructure in areas where there might not be already existing city-owned free space. Portland is not a city full of skyscrapers, so rooftop gardens and playgrounds in the downtown area would also allow many people a beautiful view of the waterfront.

Most interestingly in my mind, I propose that new and pre-existing playspaces be designed or redesigned in such a way that they are physically adaptable depending on weather conditions. Maine is known for its snowy conditions, and in the case of inclement weather, of which there is a significant amount during the winter, children are stuck inside to play. Playgrounds can be designed with automated moving parts, sensors, and computer connections to change their function based on current weather or weather forecasts. For example, a playground could have a portion that in rainy weather has a covered portion to keep segments of the playground dry and usable in the rain. Other structures can be built on inclines and designed in such a way that integrate scientific exploration in the summer vis-à-vis running water, which helps kids learn about creating and changing currents. Similarly, these structures could have a retractable cover that can then convert into speed controlled, toboggan-like apparatus creating safe snow play and allowing children to sled in more regions of Portland. Playground function would only adapt based on the current outdoor weather or the weather forecast, but seeing as Portland often has rainy or snowy weather, the playgrounds would never be too static in their function. To add to the idea of playspaces in paring garage space, playspace can be designed and built into the second to last level of a garage, providing views and air, but protection from snow and rain. Lastly, technology could also be used to identify materials that are ecologically safe and made of a material that is not slippery to gloves and mittens. So many young people, geared up in winter wear, would love to play outdoors, but cannot grip or safely maneuver play areas.

Technology can enhance a playground’s adaptability. By connecting directly to a weather forecast or Portland’s main weather system, playgrounds could be programmed to move parts prior to a change in weather. All this would take is a simple computer connection to a main database and, either automatically or at the push of a button from someone in Portland’s Recreation and Facilities Management Department, a playground would adapt its moving parts to best fit the weather circumstances. Playgrounds could also be outfitted with sensors near the entrances to gauge how many people are using them and at what times of the day and year they are most frequently using them; this data could be used for future analysis of locational placement of new playgrounds as well as reevaluation of existing playgrounds and their popularity.

New and renovated playgrounds placed in more locations around the city would impact a larger number of residents in Portland. By giving more people walking distance access to a playspace and the ability to use the playspace in all kinds of weather, more of the city’s population would be served for the better. The audience for playspaces would be primarily youth, but not only those of a high socioeconomic class. Statistically speaking, low-income students spend more time in front of a TV screen than their high-income peers and therefore are more likely to struggle with issues of obesity. Outdoor playspaces can act as a means by which to keep youth off the streets, but also limit their indoor screen time and keep them healthier.

Portland’s Comprehensive Plan, with detailed goals for recreational access for its residents, was drafted in 2002 with guidelines for a recreational plan published since 1995.

Now, almost 20 years later, it seems to me that Portland has still not met these goals for recreational space around the city. Not only does Portland’s official policy on the matter state that Portland will “develop a comprehensive management plan for the City’s park system… to meet the needs of Portland’s citizens” but it also states that Portland will “acquire and improve additional facilities in neighborhoods, which have been determined to have inadequate or insufficient open spaces and recreational resources.” I believe that Portland needs to amend its policy documents so that it can work towards giving more people the access to parks and playgrounds within walking distance of their homes and take measures to provide adequate recreational opportunities throughout all four seasons.

Conclusion:

The City of Portland is a thriving, cultural hub in northern New England. However, its play infrastructure is distributed inequitably and inadequately to its various neighborhoods. In order to provide its citizens with proper park and playspace infrastructure, Portland should amend its policy documents in order to provide more and improved playspaces throughout the city. Existing playspaces should be revamped and new ones should be created in order to give all of Portland’s youth adequate access to play. These playspaces should be designed to be technologically sound and versatile; if they are able to change their function throughout all four seasons of the year, then more youth will have access to them at all times, regardless of weather. As Carmen Harris, epidemiologist at the CDC, says, “As great as technology and engineering are, we have perhaps engineered ourselves out of physical activity.” Using technology to improve the quality of play and availability to it across all four seasons and to increase access to playspace for all of its citizens, independent of neighborhood, Portland can engineer itself back into giving more people the possibility of physical activity and show other cities the kind of technology pioneer that Portland can be.

WalkPortland: Enhancing the Pedestrian Experience in Portland, ME

WalkPortland: Enhancing the Pedestrian Experience in Portland, ME

Research question

Portland, Maine has a parking problem in its Downtown area. Residents, commuters, and tourists cite the parking situation as a detriment to the overall experience of the city. The city government is aware of the issue and has been working to modify the physical and legal structure regarding downtown parking to increase efficiency and enhance people’s experience of Portland. In my own research, I noticed a general sense of dissatisfaction with the physical capacity of downtown parking, but also a seemingly unnecessary reliance on cars for city as small in population and area as Portland.

The solution I propose is an extension of the city’s stated commitment in the 1991 Comprehensive Plan to “understand and enhance the physical framework of the built environment to assure a livable, pedestrian-oriented, human-scaled downtown.”[1] It would take the form of a mapping app, which would make parking information readily available and also serve as a legible, pedestrian-oriented map of Portland. A key feature of the app would be 5- and 10-minute walk radius maps that would hopefully help to reconnect Portlander’s perception of the city’s size and walkability to its actual area. The app would be supplemented by physical maps in downtown Portland, which increase the accessibility of this resource and also serve as advertisement for the app.

Approach to the common good for the city

The common good in the city rests in large part in the interactions between city government and the people it serves. A government that seeks to understand and respect the will of its people is one that seeks to act for the common good. This definition is cultural; it has to do with the comfortable maintenance and development of existing culture in the city. Portland’s existing policy regarding its Downtown states the city’s desire to develop the space in the best interests of the people, while being careful to maintain the existing culture and identity.[2]

Including systematic goals in writing towards respecting the people who occupy and create Downtown helps to keep “the common good” something that citizens help to define. City changes that do not align with the popular idea of common good are held accountable by town documents and goals such as that to “preserve and strengthen the unique identity and character of the Downtown.”[3]

It is also important, however, to question the existing structures and create plans and policy that keep in mind those for whom Downtown’s existing structure is not ideal, and who might prefer to see Downtown’s “unique identity” move in a different direction.

Approach to the smart city

In the age of growing populations and shrinking resources, the Smart city is efficient, safe, sustainable, and adaptable. The use of new technology is not explicit in this definition, but often the ideas or solutions that meet this description make use of new technologies. In terms of adaptability, too, the capacity of an existing structure to expand spontaneously or over time as needed speaks to its continuing usefulness and relevance; often this means that the structure is technologically updated.

In Against the Smart City, Adam Greenfield raises the important concern regarding the “seamlessness” with which technology is integrated into smart cities. He criticizes devices that are “bolt-ons rather than anything designed into the urban fabric itself ab initio.”[4] Portland’s commitment to maintaining the existing structure and identity of the Downtown presents somewhat of a challenge in utilizing new technologies in that space, but it also provides a foundation from which to build—one that ensures that the whatever solutions are put in place operate as a part of the city, rather than as an addition to it.

Greenfield also criticizes solutions in which “the collection and analysis of data [is] enshrined at the heart of someone’s conception of municipal stewardship.”[5] This hearkens back to the idea of the common good, bringing important concerns of privacy and security into the mix as the daily act of citizenship becomes a source of data-production. Because of its small size but strong sense of urbanity and community, Portland could be an excellent model of smart city technology employed with the common good very much in mind.

Besides maintaining thought of the common good, another important factor in helping smart cities to retain their “city-ness” is the concern of technological ubiquity. A city cannot be built only on smartphones, touchscreens, and Wi-Fi; it functions through human interactions. Tony Hiss[6], Guy Debord[7], and Henry Grabar[8] all speak to the place-driven, human quality of cities, especially through Hiss’s idea of “simultaneous perception” as one of the core qualities that makes a city a city. Almost as a modern day defense of Debord’s derive as a way of experiencing that quality of the city, Grabar points out, “The reverie of wandering, on foot or on wheels, can’t be calculated by an algorithm or prescribed by an app.”[9] However, technology can be used to enhance and facilitate human interactions and understandings of place, rather than make that understanding “unnecessary.” Hiss, Debord, and Grabar’s ideas are of great importance in the unique experience of being in a city, and it is possible to make them present in a smart city, as well. In terms of the WalkPortland app, keeping the app’s focus on getting people out of the shielded bubbles of their cars and out into the city is a way of using technology to promote and facilitate human interaction in the city.

Literature review

Andres Duany and Jeff Speck view “smart” not only as the utilization of new technology and design, but also as the return to some older forms of the same. Their book The Smart Growth Manual highlights “walkability” as a key feature of a smart city’s successful future. Unlike their parents’ generation, millennials (people born between approximately 1983 and 2000)[10] have tended not to buy their own cars, opting instead for a more walkable city life. And the “if you build it, they will come,” policy applies here: 64% of people first identify and move to a city they like, and then seek a job there.[11] Key to creating that desirable city image is “walkability.” Duany and Speck encourage planners to

“foster ‘walkable,’ close-knit neighborhoods: These places offer not just the opportunity to walk—sidewalks are a necessity—but something to walk to, whether it’s the corner store, the transit stop, or a school. A compact, walkable neighborhood contributes to peoples’ sense of community because neighbors get to know each other, not just each other’s cars”[12]

This community is the place for a city’s life, culture, and social capital to be created, learned, and reproduced.

In keeping with Greenfield’s concept of urban and technological seamlessness, Duany and Speck also advocate for “[taking] advantage of existing community assets: from local parks to neighborhood schools to transit systems, public investments should focus on getting the most out of what we’ve already built.”[13] One method they cite for encouraging people to leave their cars and walk is to make that the most economical option by imposing higher parking fees. This method incentivizes people to use public transportation or walk.

However, this solution raises its own set of concerns about who then gets to benefit from walkability. As Sarah Marusek discusses at length in Parking Politics, higher municipal fees such as parking costs have disproportionate effects between socioeconomic classes, and in this way parking becomes yet another way of separating those who have the right to the city and those who have the means to the city.[14] Curbside parking, an equalizer in the world of private and pay-to-stay parking lots, can be restrictive in ways that make driving possible for some and impossible for others. Marusek also cites a case study in which parking rights are connected to whether or not people can call themselves “residents.” At Amherst College, “from September through May, city streets are strictly reserved for town residents who have a town-sanctioned parking permit. This restriction is in place to keep visitors, i.e. students, from claiming parking spaces and leaving no place for ‘rightful’ residents to park during the school year.”[15] While the students reside there most of the year, they are not eligible to be considered residents of the town.

The takeaway from both Duany and Speck’s work and Marusek’s work is that urban planning innovations— smart or otherwise— have fallout of many different forms, affecting different groups of people in predictable and unpredictable ways. They key role of government in these situations is to respond not only to problems in the city but to their solutions as well.

The purpose behind the WalkPortland app is twofold: to decrease car use and car presence in Downtown Portland, and to help people to enjoy the city on foot. The decrease in car traffic may already be underway. A November 2014 article from the Portland Press Herald reported that in Maine, the populations renouncing their cars include not just the millennials that Jeff Speck cites, but Maine’s aging population as well. “At both ends of the age spectrum, people increasingly want to live near restaurants, shops, and cultural amenities.” [16] A more pedestrian-friendly Portland and pedestrian-oriented technology to accompany it would benefit multiple populations.

However, the response to the city’s varying plans to show less privilege to cars and autos is not totally positive. Portland’s plan to consolidate and shrink the Franklin arterial, thereby “[reconnecting] side streets and [improving] pedestrian and bicycle access”[17] is seen by some as a danger to the city, one that “shuts down the life blood of commerce, transit and mobility… [because] if people can’t drive here, they’ll go somewhere else.”[18] This is a serious concern to the city of Portland, which is “the financial and commercial capital of Maine.”[19] If the attempt to take cars out of Portland comes too quickly or before people are ready for it, the effects could have serious consequences for Maine’s economy.

In his lecture “The Walkable City,” Jeff Speck cites not only the enormous health benefits of walkability, but its economic, environmental, safety, and citywide benefits as well. The “inactivity borne of landscape” has more effect on obesity in America than does diet.[20] There is a direct link between the prevalence of asthma and auto exhaust emissions in urban areas.[21] The benefits of walkability are not just individual; it also fosters community and drives people to shop and buy more locally, making their communities wealthier from the inside.

And yet, the car and parking problem in Downtown Portland remains, a strain on the environment (among other things), and a major inconvenience. Apps for increased urban convenience have a large and growing market, and WalkPortland would be one of many attempts to help people navigate a city in a specific manner. The online design and tech magazine Web Urbanist ran an article listing thirteen interactive city maps, which ranged from the frivolity of a smartphone-supported citywide Pacman game called MapAttack, to the everyday usefulness of the widely popular app ParkMe, which locates open parking spots. The goal, in general, is to make the city more conveniently and easily accessible so that people can get what they want from it, when they want it. “Apps for smartphones, tablets and other gadgets are making big urban centers feel smaller than ever, making it easy to catch a ride, find cheap eats, check out street art and make new friends.”[22]

Methods

Input from actual Portland residents was immensely helpful in identifying parking as a major concern for the city, and in gauging people’s conception of the city’s size and walkability. I conducted interviews with 3 residents of Portland and 1 commuter into the city, keeping notes of how exactly they phrased their thoughts on the city. I also collected one mental map of the city from each participant. For my own perception of the city’s size and walkability, the time I spent interviewing and a transect walk to the West End were both helpful. I used QGIS to measure distances in Portland to gauge the perception of walkability against the actual distance.

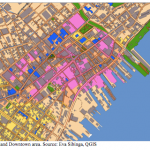

I created a simple base map of Portland, focusing on the Downtown area. I included data layers from the City of Portland that I thought would be helpful in creating a legible map for pedestrians, including of course major roads and sidewalks, but also building outlines (gray), open space (green), the boundaries of “Downtown,” (pink) historic landmarks (yellow and blue), and Metro bus routes (light blue lines). [Figure 1, Figure 2]

I concentrated on the scale of the map, and decided to keep my approach to a specific neighborhood of Portland, since my hope was to take Duany and Speck’s advice to “plan in increments of complete neighborhoods.”[23] Building outlines are an unusual inclusion in a city map, but at a pedestrian scale this seemed to make the map much more easily legible to its user. I wanted to create a map that was visually legible, appropriately scaled, and included more than just tourist attractions or sponsored locations and advertisements.

I also created a map showing the transportation network available around Portland (below). The components shown are the interstate (black), the Metro bus line (orange), the Portland Explorer tourist bus route (red), and railroad tracks (dotted black line). Once again, downtown is shown to help understand the relationship between Portland’s transportation network and its commercial center (pink). With a closer zoom, it becomes apparent that in fact Downtown is serviced more satisfactorily by Portland’s tourist bus (red) than by its city bus (orange). [Figure 3, Figure 4]

Findings

Of the four Portlanders I interviewed, three drove cars in the city. Each one of the three cited parking as source of major frustration in the city, calling it “awful,”[24] “a real difficulty” especially for those who work in Old Port,[25] and a source of dissatisfaction. Another complaint was that the city feels very much geared towards tourists, rather than residents.

Interviewees cited the small size of the city as a major upside, saying that is was “the perfect amount of city,”[26] that they enjoyed “the small town feel” and the fact that “people know you,”[27] and that the city has great, “thriving,” energy but tends to slow down by around 10 pm.[28] Each map depicted the neighborhood that the participant was most familiar with, as opposed to showing the whole peninsula or greater Portland area.

Using QGIS, I measured the length of Portland’s Downtown (as defined by the City of Portland), at .45 miles along the waterfront, and closer to .65 miles along Cumberland Avenue. The total area of the Downtown is about .25 square miles. These are all walkable distances for most adults.

Reflections / Discussion

My proposed solution is an app called WalkPortland. The app serves two main purposes. The more minor of the two is as an information source detailing where parking is available in the city. The second is as a pedestrian-oriented map application.

The parking feature of WalkPortland does not aim to make car usage and parking more convenient in Portland, or to function on a real-time basis like apps such as ParkMe[29]. While increased convenience may be a result of the app, the goal of the project is rather to have residents park their cars outside of Downtown Portland and walk to their destination, thereby reducing automobile congestion in the Downtown area (or other parts of the city) and making that a safer and more pleasant pedestrian and bicycle zone. Rather than functioning as a real-time update system for finding parking, which fosters a sense of competition and “I need to be as close as possible” that contribute to making car travel a problem in cities, the app would merely have an informational list and static map of pay lots, municipal parking and curbside parking available throughout the city. However, I anticipate that a ParkMe-like function would be highly requested.

The main focus of the app, aimed at reconnecting Portlanders’ conception of the city’s size to its actual size, is highlighted 5- and 10-minute walk radius bubbles. The goal of this feature is provide an accessible and understandable measure of Portland’s existing walkability by virtue of its scale. This will hopefully encourage people to consider walking as a viable means of transportation in the city, even across it. Using the standard average human walking speed of 3.1 miles per hour, simple calculations lead us to .25- and .5-mile radii, respectively.[30] In Portland, this translates to the entire length of the Downtown area that is walkable within 10 minutes.

Included on the app would be features important to pedestrians. Most map apps are created for car travelers and have features about traffic and toll-free routes, and leave out helpful and even crucial pedestrian information. The pedestrian map of WalkPortland would include leisure spots and amenities such as coffee shops, public restrooms, restaurants, playgrounds, grocery stores, and green space. It would also include layers that were of particular interest to pedestrian comfort and safety, such as sidewalks, street lighting,[31] public seating, bike lanes and paths, and indoor and outdoor public spaces.

To increase the accessibility of this resource so that it is not limited to those with a smartphone or an Internet connection, the maps can be made into site specific, physical, stationary maps. These maps would function the same as the app, but mapping 5- and 10- minute walk radii from their locations. These maps would serve as advertisement not only for the WalkPortland app, but also for the local businesses they would highlight. I anticipate that the primary audience for this app would be at first largely young, city-savvy smartphone users, and Portland tourists. My hope is that the app would be useful enough that anyone local might find want to have it to enhance their pedestrian experience of the city.

The WalkPortland app is an extension of existing ideas, values, and goals that the City of Portland has already set out. The app updates the technological realization of previously stated goals to help bring Portland closer to its aim of making the city more pedestrian friendly and the Downtown less congested with automobiles. Portland’s commitment to Complete Street practice and principles includes providing resources to make the pedestrian experience as pleasant and well-resourced as the driver’s.[32]

Conclusion

The WalkPortland app will help Portland drivers to get out of their cars, and it will help Portland pedestrians to get the most out of their walking experience of the city. This app will help people to think locally, and to consider walking the powerful tool that it can be in Portland. The benefits of walking are, especially in this context, manifold: to Duany and Speck this experience of the city is environmentally sustainable, community fortifying, and helpful to the literal health of the nation; to Debord, Hiss, and Grabar, the pedestrian experience of the city is of intense personal and cultural value to the city and its inhabitants; to the Portland City Council pedestrian traffic represents the alleviation of a serious congestion problem in the city’s commercial center; to Portland residents and commuters the pedestrian route is a powerful and less stressful way of understanding and moving about their city, while simultaneously helping them to engage more actively in its vibrant and thriving city life.

[1] City Council of the City of Portland ME, “Downtown Vision: A Celebration of Urban Living And A Plan For The Future of Portland – Maine’s Center for Commerce And Culture,” May 9, 1991. Accessed online December 14, 2014. http://www.portlandmaine.gov /DocumentCenter/Home/View/3376, 4.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Adam Greenfield, Against the Smart City (Do projects, 2013), Kindle edition, chap. 1.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tony Hiss, “Simultaneous Perception,” in The Experience of Place (New York: Vintage, 1991), 10.

[7] Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive and Definitions,” in The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al. (New York: Routledge, 2014), 65.

[8] Henry Grabar, “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future of ‘Spatial Thinking’,” CityLab from The Atlantic, September 9, 2014, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.citylab.com/tech/2014/09/smartphones-and-the-uncertain-future-of-spatial-thinking/379796.

[9] Grabar, “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future.”

[10] Marina Schauffler, “Sea Change: Living without cars a good sign of the times,” Portland Press Herald, November 3, 2014, accessed December 15, 2014, http://www.pressherald.com/2014/11/03/sea-change-living-without-cars-a-good-sign-of-the-times.

[11] Andres Duany and Jeff Speck, The Smart Growth Manual (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 168.

[12] Duany and Speck, The Smart Growth Manual, Appendix 1.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Sarah Marusek, Politics of Parking: Rights, Identity, and Property (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2012), 30.

[15] Ibid., 32

[16] Schauffler, “Sea Change: Living without cars a good sign of the times.”

[17] Kelly Bouchard, “Opportunity, concern seen in Portland’s plan for Franklin Street,” Portland Press Herald, October 1, 2014, accessed December 15, 2014, http://www.pressherald.com/2014/10/01/opportunity-concern-are-seen-in-arterial-plans.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Jeff Speck, “The Walkable City” (Ted Talk, TEDCity 2.0, September 2013) Accessed online December 14, 2014, http://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_speck_the_walkable_city?language=en, 7:35

[21] ibid., 12:41.

[22] Steph, “Urban Apps: 13 Interactive City Maps, Tools & Guides,” Web Urbanist, accessed December 15, 2014, http://weburbanist.com/2013/07/15/urban-apps-13-interactive-city-maps-tools-guides.

[23] Duany and Speck, The Smart Growth, Appendix 1.

[24] Josh (26, Portland resident), interview by Eva Sibinga, October 13, 2014.

[25] Brittney (23, Hollis, ME resident), interview by Eva Sibinga, October 13, 2014.

[26] Josh, interview.

[27] Brittney, interview.

[28] Marina, (22, Portland resident), interview by Eva Sibinga, October 13, 2014.

[29] www.parkme.com

[30] http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Walking.html

[31] This idea came from Eileen Johnson, Lecturer in Environmental Studies at Bowdoin College.

[32] City of Portland. Council Order 125, “Complete Streets Policy,” December 17, 2012. Accessed online December 16, 2014. http://www.smartgrowthamerica.org/ documents/cs/policy/cs-me-portland-policy.pdf.

Bibliography

Bouchard, Kelly. “Opportunity, concern seen in Portland’s plan for Franklin Street.” Portland Press Herald, October 1, 2014. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/10/01/opportunity-concern-are-seen-in-arterial-plans.

City of Portland. Council Order 125. “Complete Streets Policy,” December 17, 2012. Accessed online December 16, 2014. http://www.smartgrowthamerica.org/ documents/cs/policy/cs-me-portland-policy.pdf.

Debord, Guy. “Theory of the Dérive and Definitions.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, William Mangold, Cindi Katz, Setha Low and Susan Saegert, 65-69. New York: Routledge, 2014 [1958].

Duany, Andres, and Jeff Speck. The Smart Growth Manual. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Grabar, Henry. “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future of ‘Spatial Thinking.” CityLab from The Atlantic, September 9, 2014. Accessed September 15, 2014. http://www.citylab.com/tech/2014/09/smartphones-and-the-uncertain-future-of-spatial-thinking/379796.

Greenfield, Adam. Against the Smart City. 1.3 edition. Do projects, 2013. Kindle edition.

Hiss, Tony. “Simultaneous Perception.” In The Experience of Place. 3-26. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Marusek, Sarah. Politics of Parking: Rights, Identity, and Property. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2012.

Shauffler, Marina. “Sea Change: Living without cars a good sign of the times.” Portland Press Herald, November 3, 2014. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/11/03/sea-change-living-without-cars-a-good-sign-of-the-times.

Speck, Jeff. “The Walkable City.” Ted Talk, TEDCity 2.0, Filmed September 2013. Accessed online December 14, 2014. http://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_speck_the _walkable_city?language=en.

Steph. “Urban Apps: 13 Interactive City Maps, Tools & Guides.” Web Urbanist. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://weburbanist.com/2013/07/15/urban-apps-13-interactive-city-maps-tools-guides.

Rachel Barnes Final Paper – Flood Response App for Portland, Maine

Apologies for the lack of figures and weird format – the website wouldn’t let me upload my fine because it was too large

Rachel Barnes

Professor Gieseking – Digital Image of the City Final Research Paper, Due 12/17/2014 at 5pm

Portland Flood Response App, Website, and Road Signage

Research Question:

With industrial and technological development booming since the end of the 19th century, greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have risen and continue to rise at an increasing rate. The increasing greenhouse gas content within the atmosphere causes an increase in the warming Greenhouse Effect that produces an increase in global temperatures. Increases in global temperatures result in melting polar ice caps and land ice reservoirs, both contributing to sea-level rise over the past century, and an expansion of the oceans in a process called thermal expansion, further contributing to sea-level rise. The rising sea-level particularly affects populations and infrastructure on coastlines as they reside in areas that are most at risk of experiencing large storm surges or flooding events. As a result of these changes in global climate, Portland, Maine has experienced roughly 1.9 mm/year in sea-level rise along its coasts over the past century (Urban Land Institute, 2014). Sea-level has risen more than half a foot over the past 90 years according to a NOAA Tidal Gauge in Portland and many scientists project another 2-3 foot increase in sea-level by 2100 (Maine Geological Survey, 2007).

The sea-level rise coupled with the heightened energy in the weather and climate systems has the capacity to create larger, more powerful, and more frequent storms that damage Maine’s beautiful coastline and the industry that these regions bring the state (Urban Land Institute, 2014). I propose a policy recommendation to create a flood preparation and evacuation plan specifically tailored for Portland in the form of a smart-phone app and physical road signage detailing evacuation routes, emergency information, and weather updates. As described by Graham et al. (2012), “everyday life in urban places is increasingly experienced in conjunction with, and produced by, digital and coded information” (2). Because of this shift towards digital and coded information, I think that it would be most beneficial if Portland were to create this flood evacuation plan in the form of an electronic app and website so that it can be used and adapted to changing technology for many decades to come.

Furthermore, I propose that in order to help mitigate the damage of a serious flooding event, Portland should create a policy for limiting how close developers and industries can build to the changing coastline. I think that this is important because Portland infrastructure potentially should be sustainable and though it may not be affected by the expected 2-3 ft sea-level (Urban Land Institute, 2014) rise over the coming decades, it will likely be affected later in the century. Additionally, I suggest that Portland, Maine continue to take precaution against protecting the coastlines with more natural buffers against erosion like coastal bluffs or wetland conservation programs in an effort to avoid coastal land loss or wetland transgression inland.

Approach to the common good for the city:

As cities are ever changing and incredibly diverse, I propose that a policy recommendation with the intent of improving ‘the common good’ of the city has to have both a spatial and a temporal component. I propose that a smart city recommendation for improving the common good in Portland is something that benefits the most people possible and furthermore benefits them well into the future. I do believe that the Portland City Council is greatly concerned with the common good with regards to sea-level rise and flood preparedness as they have requested and conducted multiple different studies to gauge the timeline, likelihood, and potential damages that are associated with these incumbent flooding events. That being said, the next step in helping the common good is to create a reaction plan and to educate the City’s residents on the potential dangers of the their changing coastlines in the coming decades.

With regards to infrastructure, I proposed that this Flood Response App will be incredibly beneficial to the common good as it creates a service that initially directly improves residents’ quality of life as it allows them a certain piece of mine through educating them of the potential risks and providing them information as to how to minimize their potential losses. Furthermore, in the case of a natural disaster or flood episode, the City will have created accessible and visible evacuation plans and services to help all different demographics, specifically ages, of residents at risk. This smart city policy recommendation allows for long-term benefits to the common good and is easily executable. Outside creating the application, all the app requires is educating Portland’s residents on their evacuation route options in a flooding emergency. Though the risk of serious flooding or flood damage is not presently high, it is important that the City of Portland take action now so that they can mitigate and avoid potential problems in the future. As described by Fields and Uffer, City Councils “need to find a way to forge critical urban politics of finance focused on common welfare rather than short-term objectives of growth and competition” (13) and that the Portland City Council takes the time now and prepare the city for the impacts of future climate change.

Although substantial sea-level rise (2-3 ft) will likely not affect Portland until 2100, many commuters and residents alike complained about the lack of flood preparedness and parking during rain events this past summer. Bernie, a 21-year-old commuter from Brunswick, Maine, described the flooding and parking problems that regularly plagued the city as he commuted to work this past summer. While he was creating a mental map for this study, he suggested that the City have better planning for diverting traffic and more available alternative parking for those areas and residents affected by flooding episodes.

Approach to the smart city:

A phone application and coupled website designed to inform Portland residents of the flood warnings or storm surge events that could potentially occur in the city involves combining many different types of streaming data (weather data, emergency contact information, live updates on areas at risk, etc.) into one, smooth application and website. That being said, the application would have an offline component which would allow Portland residents to still examine the flood zones (of varying intensity based on the storm surge), emergency contact information, and areas of higher elevation within the city on their phones for times when electricity or cell phone service may be down. In addition to the application’s offline component, there should also be incredibly visible signage all across the city showing the same topography, flood zone, emergency contact information, and evacuation plans, so that those residents or tourists without access to the internet can also move to safety in the event of a flood in Portland. An ideal place for these signs and information would be at every bus stop.