Hannah Rafkin

The Digital Image of the City

Professor Jen Jack Gieseking

12/17/14

BoostPortland: Grappling with Homelessness in the Smart City

Research Area

In the United States, national homelessness declined by over 9% from 2007 to 2013. In the state of Maine, homelessness increased by 17% from 2009 to 2013. In the same timespan, homelessness has increased by 70% in the city of Portland, growing at four times the rate of the state. [1] The city is well known for its extensive support infrastructure, particularly Preble Street Resource Center. Preble Street has been extensively hailed for its “housing first” model, in which people are given housing regardless of substance abuse or mental health problems. Despite the excellence of Portland’s resources for the homeless, these centers are overwhelmed. Shelters often have spillover, leaving many people curling up on chairs or on the floor, oftentimes in other facilities. One cold night in 2013, only 272 shelter sleeping spots were available for double the number of people who sought them out. [1]

The Task Force to Develop a Strategic Plan to Prevent & End Homelessness in Portland reported on the demographics of Portland homelessness as of 2012. The average age of a shelter-goer was 40. Nearly 60% faced mental illness, and nearly 38% grappled with drug addiction – 70% reported a combination of the two. At Florence House, Preble Street’s housing unit for chronically homeless women, 66% were victims of abuse, 54% victims of domestic abuse specifically. Seventy one percent of homeless people had been homeless for a month or less. [2] According to a Bangor Daily News article, a third of homeless people in Portland’s shelters are from the city, another third are from other Maine towns, and another third are from out of state. [3]

Policy Controversies

The City Council of Portland discussed extensive plans to address these issues in the same 2012 report. Their goals included “Retooling the Emergency Shelter System, Rapid Rehousing, Increased Case Management, and Report Monitoring.” Specifically this meant creating a centralized and streamlined intake and assessment process, developing additional housing units, increasing rental opportunities, working with landlords to make housing more accessible, adopting and enhancing an ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) case management system, and increasing work and educational opportunities for homeless youth, families, and veterans. [2]

The Portland Chamber of Commerce responded negatively to the task force and the presence of the homeless population more generally, wondering if the city of Portland was “too attractive to the homeless.” [3] The president of the Downtown District said the homeless were “intimidating,” and “hurt [Portland’s] ability to be a tourist destination and also our business.” [4] The Chamber expressed concern that the city was becoming “a disgusting filthy mess.” [3] Mark Swann, director of Preble Street Resource Center, was “deeply saddened and disappointed by…the misguided and mean-spirited comments…Dehumanizing our neighbors struggling with poverty, homelessness and hunger is deplorable.” He advised the Chamber to talk with Preble Street’s councilors to get a better sense of the “attractiveness” of homeless life in Portland. [4]

These contrasting attitudes represent a growing tension in Portland between wealthy gentrification and impoverished homelessness. As homelessness has skyrocketed in recent years, the city has become increasingly trendy – ‘hipster’ cafes, pricey shops, and condos-with-a-view have sprung up incessantly. Swann’s suggestion for conversation between the Chamber and the Resource Center is wise – these seemingly opposing forces could benefit from dialogue instead of distant and impassioned resentment.

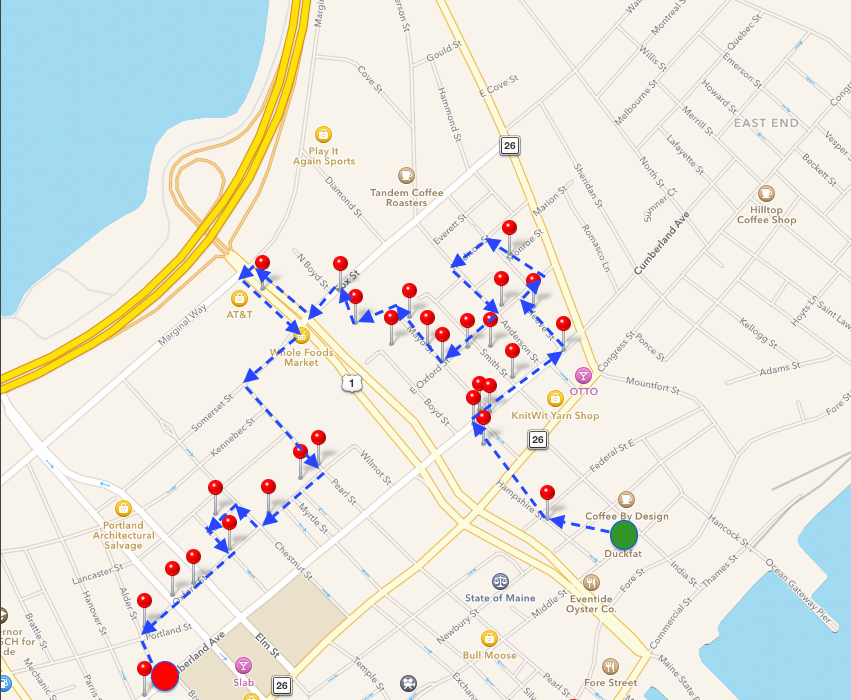

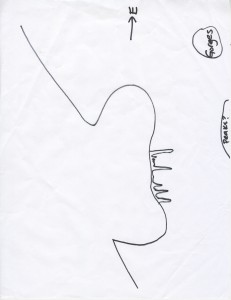

I observed this conflict of interests in action during my transect walk through Portland, noticing the strained simultaneity of homelessness and gentrification. I was particularly struck by a juxtaposition I observed at the busy intersection of Franklin Street and Marginal Way. A homeless man stood leaning against a road sign, holding up a flimsy piece of cardboard. Yards away was a store called Planet Dog, catering exclusively to the bedding, food, toys, and accessories of Portland’s canines. An astronomically expensive antique shop and a home entertainment center sat down the road from Preble Street Resource Center.

Later on, another juxtaposition presented itself. I was walking through Congress Square Park taking photographs and surveying the scene. Some people sat on the steps, one man grilled burgers, another played guitar. My taking pictures clearly upset a woman sitting on a bench, who got up and followed me for several blocks, slurring and staggering, yelling “Fuck the white house, bitch” and other obscenities. Nonsensical as the specific expression of her outrage may have been, this encounter was representative of a larger urban tension. I am a white girl from New Jersey, doing coursework for a course at an elite college, wielding an imposing SLR camera in the attempt of ‘capturing the city,’ only visiting for a brief and comfortable afternoon of exploration. In that instance, I was encroaching on her space – she does not have the option to ‘explore’ the city lightheartedly.

Layers of Congress Square Park

Boost Portland – Smart City Solution

A man I interviewed outside of Preble Street said that complications of daily life and a lack of affordable housing make it “impossible for people to get on their feet” in Portland. I propose a combined application, website, and texting service called BoostPortland, aimed to get Portland’s at-risk population on their feet – and to keep them on their feet – by meeting everyday, individualized needs beyond sleep and food. BoostPortland will draw on the city’s own residents, businesses, and organizations to to support the city’s neediest citizens, creating a pervasive network dedicated to bettering their community. BoostPortland will provide a platform for the struggling citizens of Portland to receive help in confronting the myriad challenges of daily life.

Users would create posts, either offering or seeking out assistance. An individual could post offering help with resumes at the public library, advertising an odd job like shoveling a driveway, or giving away clothing items. Somebody could post requesting a ride to a job interview, asking for a winter jacket, or seeking help with English. Businesses could post offering free food, wireless Internet, a space to organize, or perhaps just some time to warm up.

This format allows for direct and impactful volunteerism on the terms of both the giver and the receiver. Specific, attainable needs will be met at a convenient time and a convenient place for both parties, while creating connections between Portlanders of varied backgrounds. Additionally, involving a diverse group of businesses – from Salvation Army to Portland Architechtural Salvage – might help to ground them in the often-grim realities in the city. This might give them a better understanding of the challenges facing the homeless population, and allow for increased awareness of the role of commerce in making Portland an increasingly expensive place to live. Ideally, businesses will then reconsider the sentiments expressed by the Chamber of Commerce in response to the task force.

Approach to the Common Good for the City

Urban centers are hotbeds of diversity. Socioeconomic, racial, cultural, sexual, and lifestyle differences guarantee exposure to fresh perspectives. In a city with a focus on the common good, all perspectives are given a voice, and there exists a platform for productive and engaging “encounter and exchange.” [5] In a city with a focus on the common good, all citizens have access to basic human rights – water, food, and shelter are attainable for everyone. In a city with a focus on the common good, there is a network of organized care and action around issues of social justice impacting the city.

The homelessness task force is on the right track to meeting this definition (though its website’s most recent agenda item is dated October 11, 2012) but the Chamber of Commerce’s focus on business and tourism poses roadblocks in attaining the common good in Portland.

Approach to the Smart City

The ambitious and futuristic proposals to re-envision the technological functioning of the modern day city in “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments” are exciting. [6] But the idea of “everything [becoming] a sensor” is perhaps overzealous, and has major potential to verge into Big Brother territory. [6] The focus on using technology to better conserve energy is very appealing, however.

A truly smart city integrates technologies that are “situated in a specific locale and human context,” as described by Adam Greenfield. [7] South Korea’s city of Songdo exemplifies the pervasiveness of technology described in Crowley, Curry, and Breslin’s article, but lacks contextual concern for the interests, behaviors, and problems facing its citizens. Songdo was built before those interests, behaviors, and problems could even manifest, before city planners could consider how their innovations would function within the specific flow and feel of the city. In the smart city, citizens define the technology; the technology does not define the citizens.

As technologies tend to be expensive, they come with concerns of accessibility. The smart city does not limit its innovations to “those who can afford it and conform to middle-class rules of appearance and conduct.” [8] This notion is particularly pertinent to my research area.

Literature Review

“To Go Again to Hyde Park” by Don Mitchell emphasizes each citizen’s “right to the city,” though those rights are not always made equal in practice. [5] As “some members of society are not covered by any property right,” they must “find a way to inhabit the city…as with squatting, and with the collective movements of the landless, to undermine the power of property and its state sanction, or otherwise appropriate and inhabit the city.” [5] Mitchell advocates for the marginalized populations’ participation – forcefully, if need be – in the dialogue of urban life. In “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space,” Dolores Hayden also stresses the importance of undervalued voices in urban conversation. She discusses the development of the urban landscape, describing the role of every inhabitant of a city, the marginalized included, in shaping its look, feel, and experience: “Indigenous residents as well as colonizers, ditchdiggers as well as architects, migrant workers as well as mayors, housewives as well as housing inspectors, are all active shaping the urban landscape.” [9]

Technology continues to reform the way citizens interact with each other and share ideas, even within disenfranchised populations. The homeless community’s usage of cell phones has skyrocketed in recent years. In 2009, advocates from Washington D.C. estimated that 30%-45% of the homeless population they worked with owned cell phones. [10] In a 2010 study of homeless cell phone use in Philadelphia, 44% of a 100-person sample size owned cell phones. [11] A 2013 study found that 70.7% of Connecticut homeless emergency room patients owned cell phones. [12] No such study exists for Portland, but similar patterns likely apply. As the homeless population becomes increasingly technologically active, a solution like BoostPortland gains potential to foster discussion and exchange between the haves and have-nots of the city, drawing on the broader community to improve the lives of Portland’s neediest citizens.

Integrating technology into such projects must be done thoughtfully, however. At a 2012 technology conference in Austin, Texas, a marketing agency proposed that homeless people be utilized as mobile wireless Internet transmitters. For $20 a day, homeless people walked around wearing shirts that said “I’m _____, A 4G Hotspot.” Instead of creating inclusive dialogue, this “charitable experiment” denied the personhood of the participants, defining individuals only by their potential for beneficial functionality. One blogger aptly described the project as “something out of a darkly satirical science-fiction dystopia.” [13]

The Hack to End Homelessness meet up in Seattle provides a better model for conscientious use of technology – developers, designers, and “do-gooders” got together to brainstorm solutions for homelessness. The event produced exciting data, maps, applications, and other programs with a focus on dialogue between groups with different staked interests – the event organizer foregrounded the importance of “[reducing] tension between the housing community and tech workers.” [14]

Methods

Representing the homeless through maps was a difficult undertaking – without an address, homeless citizens do not get represented in government census data. Data about issues surrounding homelessness exists (housing, income, neighborhoods). Social Explorer median income census data and the ‘PlanNeighborhoods’ Portland Shapefile were particularly helpful in establishing a backdrop for new data about homelessness directly.

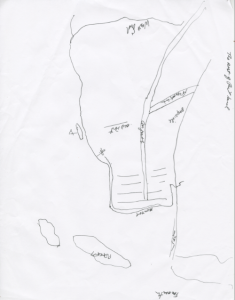

I created new data sets on Portland’s homeless encampments, resource centers, and affordable housing. I began by geocoding the addresses of all of the homeless encampments mentioned in the Portland Press Herald in the past three years to get a sense of where the homeless are congregating. Then, I placed these data points on top of median income data to juxtapose the temporary homes of the homeless with the financial context of their temporary surroundings. This layer provides a means of accounting for transient homes of those that the census does not count – an attempt to bring the homeless onto the city map. I also geocoded all of Portland’s resource centers, shelters, and soup kitchens, and placed them on the same map as the encampments to see where help is concentrated in the city and where it is lacking. As the dearth of affordable housing has made living a stable life in Portland increasingly difficult, I was curious about the prevalence and whereabouts of existing affordable housing in the city, so I mapped housing units deemed affordable by the Maine State Housing Authority. [15]

Findings

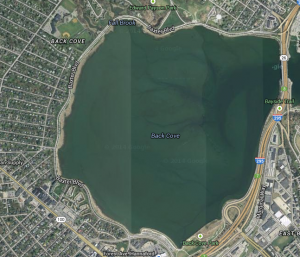

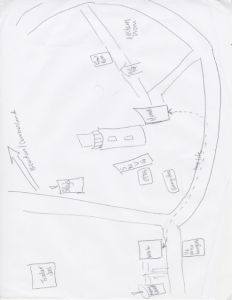

As the above map demonstrates, the homeless are inclined to camp near the water and in wooded areas. They camp mostly in low- to middle-income regions, though not exclusively. The city’s resource centers are mostly concentrated in a small pocket in Bayside, a low-income region of Portland. The encampments and resource centers do not show significant overlap in location.

The above map shows that housing deemed affordable by the Maine State Housing Authority is centralized in the Downtown, Bayside, and East End regions of Portland. It is interesting and concerning to consider the consequences of sectioning off low-income populations, reminiscent of tenement-style urban layouts that Hayden discusses in “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” [9]

Reflections: Technological Concerns

BoostPortland will have three technological components to support the expected range of socioeconomic backgrounds: a smartphone application, a website, and an SMS texting service. The smartphone application will likely appeal to a more economically stable faction of users, as they are more likely to own them. It will have a simple and clean interface. There will be four tabs: Get Help, a list of the day’s offers, Give Help, a list of the days requests, Map, a map version of both lists, and Post, an interface for users to offer or request assistance. Users can click on an offer or a request for more details, linking to contact information of the poster. The website will be structured identically. The SMS service will allow those with basic cell phones to request or give assistance on the move. Users can text in requests or offers, to be added to the daily lists. Users can also subscribe to a daily text containing one or both lists, and can text in a reply to be put in contact with the giver or receiver of help.

This technology-driven idea of a combined application, website, and texting service – aimed to assist Portland’s most disenfranchised population – comes with obvious challenges. Without such basic amenities as consistent shelter or food, the homeless and impoverished are much less likely than the average Portlander to have access to such technologies. However, homeless people nation-wide are becoming increasingly technologically connected, as shown by the aforementioned studies on homeless cell phone use in Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and Connecticut. With these changes, homeless people will have increasing accessibility to solutions in the form of apps and websites, and especially basic SMS texting. This is particularly true of homeless youth and the recently homeless, as noted by Mark Swann, director of Preble Street. Additionally, Preble Street and the Portland Public Library have free computers where users could access the website component of BoostPortland.

Policy Recommendation

Portland’s homelessness task force has laid out some very important goals. I suggest that the City Council involves the Chamber of Commerce in achieving them to augment the city’s response to homelessness. Getting businesses involved in the issue will give them a broader understanding of what is happening to the marginalized populations in the city. This approach will also give the Council more power and leverage in addressing their goals, while creating productive dialogue between seemingly antagonistic forces, as Hack to End Homelessness sought to do. In light of the Chamber of Commerce’s commentary on the task force and, most likely, reticence to help, the City Council might create an incentive program to draw the Chamber to the Portland’s social justice issues.

Conclusion

BoostPortland foregrounds the voices of those in need by creating a communal network of Portlanders determined to face the growing problem of homelessness. By including local businesses and addressing gentrification head on, it has the potential to bridge the gap between monetary interests and humanitarian interests. I believe that this solution can make Portland a smarter, more connected, and more engaged city.

Works Cited

[1] Billings, Randy. “Homelessness Hits Record High in Portland.” Portland Press Herald. October 27, 2013. http://www.pressherald.com/2013/10/27/homelessness_hits_record_high_in_portland_/.

[2] “Report of the Task Force to Develop a Strategic Plan to Prevent & End Homelessness in Portland.” Portland City Council. November 16, 2012. https://me-portland.civicplus.com/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Item/132?fileID=695.

[3] Koenig, Seth. “Is Portland ‘too attractive’ to homeless people?” Bangor Daily News. December 21, 2012. http://bangordailynews.com/2012/12/21/news/portland/are-cities-like-portland-too-attractive-to-homeless-people/.

[4] Murphy, Edward. “Preble Street Head Decries Chamber Remarks on Homelessness.” Portland Press Herald. November 16, 2012. http://www.pressherald.com/2012/11/16/preble-street-head-decries-chamber-remarks-on-homelessness/.

[5] Mitchell, Don. [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al. New York: Routledge, 2014)

[6] Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. 2014. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, edited by Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre, 379–99. Springer.

[7] Greenfield, Adam. 2013. Against the Smart City. 1.3 edition.

[8] Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Micheal Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 163-72. New York: Routledge, 2014

[9] Hayden, Dolores. 1997. “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” In The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, 14-43. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[10] Dvorak, Petula. “D.C. Homeless People Use Cellphones, Blogs, and E-Mail to Stay on Top of Things.” The Washington Post. March 23, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/22/AR2009032201835.html.

[11] Eyrich-Garg, Karin. “Mobile Phone Technology: A New Paradigm for the Prevention, Treatment, and Research of the Non-sheltered “Street” Homeless?” US National Library of Medicine. April 16, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2871091/.

[12] Eysenbach, Gunther. “New Media Use by Patients Who Are Homeless: The Potential of MHealth to Build Connectivity.” US National Library of Medicine. September 30, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3786002/.

[13] Wortham, Jenna. “Use of Homeless as Internet Hot Spots Backfires on Marketer.” The New York Times. March 12, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/13/technology/homeless-as-wi-fi-transmitters-creates-a-stir-in-austin.html?_r=0.

[14] Soper, Taylor. “Hack to End Homelessness: Maps, Social Networks and Other Ideas to Help Seattle’s Homeless – GeekWire.” GeekWire. May 5, 2014. http://www.geekwire.com/2014/hack-end-homelessness-recap-maps-social-networks-startup-ideas/.

[15] “Cumberland County Affordable Housing Options.” Maine State Housing Authority. December, 2014. http://www.mainehousing.org/docs/default-source/housing-facts—subsidized/cumberlandsubsidizedhousing.pdf?sfvrsn=5.