[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Productive-Learning-in-Portland-small.pdf”]

Category Archives: Infrastructure

Optimizing Portland, Maine’s Public Information Access: Coupling Cloud Technology with Physical Kiosks for Seamless Urban Connectivity

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/DIOTC-Final-Paper-web.pdf”]

Rachel Barnes Final Paper – Flood Response App for Portland, Maine

Apologies for the lack of figures and weird format – the website wouldn’t let me upload my fine because it was too large

Rachel Barnes

Professor Gieseking – Digital Image of the City Final Research Paper, Due 12/17/2014 at 5pm

Portland Flood Response App, Website, and Road Signage

Research Question:

With industrial and technological development booming since the end of the 19th century, greenhouse gases in the atmosphere have risen and continue to rise at an increasing rate. The increasing greenhouse gas content within the atmosphere causes an increase in the warming Greenhouse Effect that produces an increase in global temperatures. Increases in global temperatures result in melting polar ice caps and land ice reservoirs, both contributing to sea-level rise over the past century, and an expansion of the oceans in a process called thermal expansion, further contributing to sea-level rise. The rising sea-level particularly affects populations and infrastructure on coastlines as they reside in areas that are most at risk of experiencing large storm surges or flooding events. As a result of these changes in global climate, Portland, Maine has experienced roughly 1.9 mm/year in sea-level rise along its coasts over the past century (Urban Land Institute, 2014). Sea-level has risen more than half a foot over the past 90 years according to a NOAA Tidal Gauge in Portland and many scientists project another 2-3 foot increase in sea-level by 2100 (Maine Geological Survey, 2007).

The sea-level rise coupled with the heightened energy in the weather and climate systems has the capacity to create larger, more powerful, and more frequent storms that damage Maine’s beautiful coastline and the industry that these regions bring the state (Urban Land Institute, 2014). I propose a policy recommendation to create a flood preparation and evacuation plan specifically tailored for Portland in the form of a smart-phone app and physical road signage detailing evacuation routes, emergency information, and weather updates. As described by Graham et al. (2012), “everyday life in urban places is increasingly experienced in conjunction with, and produced by, digital and coded information” (2). Because of this shift towards digital and coded information, I think that it would be most beneficial if Portland were to create this flood evacuation plan in the form of an electronic app and website so that it can be used and adapted to changing technology for many decades to come.

Furthermore, I propose that in order to help mitigate the damage of a serious flooding event, Portland should create a policy for limiting how close developers and industries can build to the changing coastline. I think that this is important because Portland infrastructure potentially should be sustainable and though it may not be affected by the expected 2-3 ft sea-level (Urban Land Institute, 2014) rise over the coming decades, it will likely be affected later in the century. Additionally, I suggest that Portland, Maine continue to take precaution against protecting the coastlines with more natural buffers against erosion like coastal bluffs or wetland conservation programs in an effort to avoid coastal land loss or wetland transgression inland.

Approach to the common good for the city:

As cities are ever changing and incredibly diverse, I propose that a policy recommendation with the intent of improving ‘the common good’ of the city has to have both a spatial and a temporal component. I propose that a smart city recommendation for improving the common good in Portland is something that benefits the most people possible and furthermore benefits them well into the future. I do believe that the Portland City Council is greatly concerned with the common good with regards to sea-level rise and flood preparedness as they have requested and conducted multiple different studies to gauge the timeline, likelihood, and potential damages that are associated with these incumbent flooding events. That being said, the next step in helping the common good is to create a reaction plan and to educate the City’s residents on the potential dangers of the their changing coastlines in the coming decades.

With regards to infrastructure, I proposed that this Flood Response App will be incredibly beneficial to the common good as it creates a service that initially directly improves residents’ quality of life as it allows them a certain piece of mine through educating them of the potential risks and providing them information as to how to minimize their potential losses. Furthermore, in the case of a natural disaster or flood episode, the City will have created accessible and visible evacuation plans and services to help all different demographics, specifically ages, of residents at risk. This smart city policy recommendation allows for long-term benefits to the common good and is easily executable. Outside creating the application, all the app requires is educating Portland’s residents on their evacuation route options in a flooding emergency. Though the risk of serious flooding or flood damage is not presently high, it is important that the City of Portland take action now so that they can mitigate and avoid potential problems in the future. As described by Fields and Uffer, City Councils “need to find a way to forge critical urban politics of finance focused on common welfare rather than short-term objectives of growth and competition” (13) and that the Portland City Council takes the time now and prepare the city for the impacts of future climate change.

Although substantial sea-level rise (2-3 ft) will likely not affect Portland until 2100, many commuters and residents alike complained about the lack of flood preparedness and parking during rain events this past summer. Bernie, a 21-year-old commuter from Brunswick, Maine, described the flooding and parking problems that regularly plagued the city as he commuted to work this past summer. While he was creating a mental map for this study, he suggested that the City have better planning for diverting traffic and more available alternative parking for those areas and residents affected by flooding episodes.

Approach to the smart city:

A phone application and coupled website designed to inform Portland residents of the flood warnings or storm surge events that could potentially occur in the city involves combining many different types of streaming data (weather data, emergency contact information, live updates on areas at risk, etc.) into one, smooth application and website. That being said, the application would have an offline component which would allow Portland residents to still examine the flood zones (of varying intensity based on the storm surge), emergency contact information, and areas of higher elevation within the city on their phones for times when electricity or cell phone service may be down. In addition to the application’s offline component, there should also be incredibly visible signage all across the city showing the same topography, flood zone, emergency contact information, and evacuation plans, so that those residents or tourists without access to the internet can also move to safety in the event of a flood in Portland. An ideal place for these signs and information would be at every bus stop.

The application would also be used as a way to connect emergency services and flood victims. The application could be used to either request emergency help or to let the emergency services know that specific residents are safe and healthy – this service would be especially important for the elderly and minor population as they may require more assistance in natural disasters. Additionally, this last component of this flood response application could serve for a way for more long distance family members to check up on the status of their family or request information as to whether they have been located by emergency services. As the emergency services personnel rescue or help individual residents, they could also use the app as an online message board or database for all individuals that have been found or are missing.

Literature review:

There have been many inquiries by the Portland City Council to obtain as much information as possible about which areas and infrastructures are most at risk from the incumbent sea-level rise. After a 1995 Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report titled Anticipatory Planning for Sea-Level Rise Along the Coast of Maine, the City became more aware of the threats to their coastlines. The report compiled information from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) from 1992 that stated that the international science community projects an accelerated rate of sea-level rise as a result of global climate change associated with the greenhouse effect. Similarly, the IPCC projects that there will be a global rise in sea-level in the range of 33-110 cm (1.08 – 3.61 ft) by the year 2100. The EPA report argues that the United States IPCC recommends that coastal zone managers, i.e. the Portland City Council, evaluate impacts on sea-level rise based on considerations of at least a 1.0 meter rise scenario for 2100 (EPA, 2014). Gordon Hamilton of University of Maine’s Climate Change Institute further supports the IPCC prediction of a 1m rise in sea-level by 2100 is supported by (Maine’s Coastline Program, 2007).

The EPA report also urges coastal communities in Maine to address the issue of flooding and sea-level rise now as there is a projected gradual onset of the issue, and there is time to make changes and an opportunity to avoid adverse impacts by acting now (EPA, 2014). The EPA moreover urges Maine’s coastal communities to seek “no regrets” strategies; no regret strategies are defined as strategies that the State will not regret implementing even if there is no acceleration in the rate of sea-level rise and strategies that recognize that sea-level rise is just one factor affecting coastal land loss (EPA, 2014). The report concludes by recommending that “the state should protect and strengthen the ability of natural systems to adjust to change in shoreline position” (11) and that “the state should prevent new development which is likely to interfere with the ability of natural systems to adjust to changes in shoreline position” (11).

There exist many other reports stemming from this initial EPA report (Anticipating Rising Seas from the Maine Coastal Program (2007) and the Waterfronts of Portland and South Portland Maine from the Urban Land Institute (2014)) and it is clear that the City Council is making the appropriate moves to prepare for sea-level rise in the future. Unfortunately, the council has yet to create any publically available response or evacuation plans.

The Maine Coastal Program report reiterates the same information as the EPA report did in 1995, but is more accessible and easily understandable, suggesting that its target audience was less scientific or political and more of a residential audience. The report emphasized the evidence of an increase in global temperatures and its contribution to more energy to the climate system in general. The report describes the stronger winds, larger waves, larger storm surges, and more erosion associated with a higher energy system. The report also warns residents of the economic impacts of such a shift in sea-level and its associated impacts in terms of the clamming and lobster industries along the coast of Maine (Maine Coastal Program, 2007).

As described by Stephen Dickson of the Maine Geological Survey, the increased energy within the weather system resulting from increasing global temperatures has a drastic effect on the intensity of weather events in coastal regions. He states that “storm surge from more intense weather systems could compound the damaging effects of sea-level rise” (1) and that coastal Maine is largely affected by Nor’easters, in which rapid changes in wind direction and currents combine to pile water along the coast and cause hefty erosion and flooding damage to coastal areas. According to Dickson, during such storm events, water levels could increase an additional 1 to 3 feet on top of the already rising sea-levels (Maine Coastal Program, 2007). Dickson and Peter Slovinsky, also of the Maine Geological Survey, argue that the densest population in Maine (York and Cumberland Counties) coincides with the most vulnerable coastal geology (sandy beaches, estuaries, and mud and cobble bluffs). The coastal regions of York and Cumberland County could experience potentially major economic such as declines in tourism and loss of taxable revenue after the loss or submersion of expensive waterfront homes (Maine Coastal Program, 2007). Dickson suggests that towns should adopt new measures that anticipate sea-level rise such as planning boards revising floodplain ordinances to raise the minimum height for building 3 feet over the existing 1-foot freeboard (Maine Coastal Program, 2007).

In their Resolution Supporting the Development of a Sea-Level Rise Adaptation Plan (2011), Portland City Council agreed to accept a 3-6 feet sea-level rise over the next 100 years which may cause permanent flooding in certain low elevation areas of the City. The council agreed that potential permanent flooding represents an economic, cultural, ecological, and public infrastructure loss to the City and that the Portland City Council supports the development of a sea-level rise adaptation plan (Portland City Council, 2011). That being said, I urge the City Council to explore the many different ways that a cell phone application and website can aid residents and their families during natural disasters.

There are many other instances of natural disasters where social media and technology have been used to aid or search for missing persons. More specifically, Twitter was arguable the most reliable source for live news updates and information for New York City, NY during Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Luckily, in New York, although millions of people lost power during the storm, individuals were still able to access the Internet on their mobile devices. Multiple different large media groups like Huffington Post and the news aggregator BuzzFeed experienced failing servers and therefore turned to Twitter and other social media to deliver information and reports about the storm. According to Twitter, people tweeted more that 20 million times about Hurricane Sandy from October 27th to November 1st and the most popular conversation on Twitter was about news and information, followed by photos and videos, then hopes and prayers for safety (Pew Research Journalism Project, 2012).

Additionally, after the earthquake in Turkey in 2011, Google launched a Person Finder app designed to help victims find missing loved ones. This project was first developed in response to the earthquake in Haiti in 2010 and has been deployed in several other disaster zones like Japan after their tsunami in 2011 since. The application was very simple and was created within a number of hours; users could either enter information on the person they were looking for or add information about people who are not already accounted for (Toor, 2014). It is this kind of combination between online, live news outlets (similar to Twitter during Hurricane Sandy in 2012) and a Person Finder app (similar to Google’s app during the earthquake in Turkey in 2011) that I think would be most beneficial for the City of Portland to develop for flood response.

In a 2013 article from the Bangor Daily News, titled Sea-level rise will wash away $46.4 million worth of Portland’s Commercial Street Properties by 2100, architects say, Seth Koenig describes the potential economic impacts of rising sea-levels and larger storm surges on Portland’s Commercial Street. He writes that nearly $33 million in flood damage will occur along Portland’s low-lying and high-traffic Commercial Street area by 2050 due to sea-level rise. According to the report released by local group, Portland Society for Architecture and analysis done by the consulting firm, Scarborough-based Catalysis Adaptation Partners, losses will actually amount to $111 million by 2100 resulting from sea-level rise. The $46.4 million dollar loss represents the specific land parcels that will be inundated by water on a daily basis resulting from high tides if no changes are made. These estimates are made specifically for Portland’s waterfront Commercial Street and Old Port, and do not take into account Back Cove or the city’s Bayside neighborhood which are also considered at high risk for sea-level rise and associated storm surges (Bangor Daily News, 2013).

Methods:

In order to understand the types of smart city solutions that Portland would most benefit from, I researched various smart city solutions that would benefit both already existing non-smart cities that are taking steps to become more ‘smart’ (i.e Portland, Maine or New York, New York) and already existing smart cities (i.e Songdo, South Korea). After this research, I executed a transect walk through Munjoy Hill in Portland, a Café Ethnography in Speckled Ax Café, and collected four mental maps from three residents and once commuter in Portland. After determining that a Flood Response application was most beneficial to Portland, I collected various sets of Portland age distribution data from U.S Census data off Social Explorer. I focused mainly on the elderly population (65+) and the minor population (18-) as they are both potentially the most at risk to both present flood risks and future flood risks as sea-levels are expected to rise over the next 85 years. I combined the U.S census data with multiple data layers such as elevation (topography), flood zones, and locations of hospitals and fire stations from the City of Portland in an effort to assess the riskiest locations in terms of flood risk over the next 85 years . The following maps are the maps created from these various data sources with the program QGIS.

As seen in figure 1, there are various areas that are particularly at risk to flooding in Portland. The areas that are especially at risk are the East Bayside and West End neighborhoods and the areas surrounding the Fore River, just south of the City. Furthermore, there are more areas in central Cumberland County, outside of the city of Portland, that also lay in flood zones. Additionally, the contours in figure 2 addresses the fact that other areas in and around Portland are also at risk as they sit at or below sea-level. The other areas that are of high risk to flooding are Back Cove and the area between Libbytown and West End. As seen in figure 3 (following page), the largest populations of elderly people exist in the more northern parts of Cumberland County and in Back Cove. As seen in figure 2 and 1, back cove is in a very low-lying area and therefore has a very high risk of flooding.

As seen in figure 4 (following page), there are fewer minors living in the coastal regions and there are higher minor populations living in the Northern regions of Cumberland County. Additionally, is a relatively large population of minors in East Bayside and Back Cove, both regions that are at a high risk of flooding within the coming decades.

As seen in the map in figure 5, the areas that are most heavily populated with elderly residents (Back Cove and the region just north of Back Cove) are also the same regions that lay below sea-level. Additionally, in figure 6 (below), the largest population of minors, in the more northern parts of Cumberland county, also coincide with the regions of the county that are most at risk for flooding and sea-level rise in the coming decades. In a hypothetical situation, if these current minors were to grow up and live their entire lives in these neighborhoods in Portland and Cumberland county, they theoretically would be part of the elderly population that is seriously at risk by the time climate change and sea-level rise sets in later in the century.

Reflections/Discussion:

As seen in the maps above, a large portion of Portland’s land sits at an elevation below sea-level. These low-lying areas have a current high flooding risk, even before sea-level rises. That being said, the flood zone areas that the City of Portland outlined in 2009 do not necessarily cover these regions. This could be for many different reasons – potentially the bedrock in these areas is impervious and therefore when inundated with water, the water quickly runs off to other regions of low elevation. That being said, I would suggest that the areas of elevation in Cumberland County that are below sea-level should be added to the flood zones. Additionally, there are fire stations that sit in the middle of low-elevation and flood zone regions. These locations are both potentially great and potentially horrendous ideas. On the one hand, the emergency services would be close to those residents in, but on the other hand, the stations and all of their equipment would also be flooded, making it difficult for the emergency services to do aid flood victims.

Moreover, there are large areas in Portland and the greater Cumberland County that run a high risk of flooding as they have such shallow topography and that also have large elderly populations, specifically Back Cove and the region just north of there. It is incredibly important that there are clear and visible signs in this region for evacuation routes and flood plans to regions of higher elevation and that there are easily accessible roadways for emergency services to aid these regions as well as hospitals. Perhaps large amounts of road signage may be considered extreme or expensive and therefore not worth it. I would argue that it will be worth it in the long run and I would further suggest that the City of Portland encouraging elderly residents to avoid living in the Back Cove, West End, or Fore River areas in an effort to avoid potential flood risks and hazards in the future.

Conclusion:

Though these plans seem premature as there is a relatively small risk of flooding in the next few years, having plans in place now will simply mean that the City of Portland is prepared in the coming decades when sea-level rise when flooding may become a problem. Additionally, one may argue that making such large policy changes to building distributions along the coast is detrimental to the current flow of the city and the city’s coastal economic activity, I would respond with an idea from Sorkin (1999) about the reciprocity within cities – “Cities are reciprocal, open and flexible ensembles and can continuously remold themselves through repeated social interactions”. If the City of Portland were to commit to this flood response plan and policy recommendation now, it would adapt and become a stronger, more prepared, and smarter city in the future.

Works Cited:

Fields, Desiree., Uffer, Sabina. “The Financialisation of Rental Housing: A Comparative Analysis of New York City and Berlin.” Urban Studies July 2014 (2014).

Graham, Mark. “Augmented Reality in Urban Places: Contested Content and the Duplicity of Code.” Transactions of the Insitute of British Geographers (2012).

Guskin, Emily., (2012) “Hurricane Sandy and Twitter.” In Pew Research Journalism Project: PEJ New Media Index.

Koenig, Seth. “Sea-Level Rise Will Wash Away $46.4 Million Worth of Portland’s Commercial Street Properties by 2100, Architects Say.” Bangor Daily News October 24th (2012).

City of Portland., GIS Data, 2014.

Coyne, J. R., Anton, J. M., Richards Waxman, D., Duson, J. C., (2011). Resolution Supporting the Development of a Sea-Level Rise Adaptation Plan. Portland City Council, July 18th.

Maine Coastal Program. “Anticipating Rising Seas.” Maine Coastline Winter (2007).

Simone, AbdouMaliq. “People as Infrastructure: Intersecting Fragments in Johannesburg.” The People, Place, and Space Reader (2004): 240-46.

Slovinsky, Peter. “Preparing Portland for the Potential Impacts of Sea Level Rise.” Maine Geological Survey (2011).

Sorkin, Michael. “Introduction: Traffic in Democracy “. The People, Place, and Space Reader (1999): 411-15.

Toor, Amar. (2011). “Google Launches Person Finder App Following Earthquake in Turkey.” www.engadget.com.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), (1995). Anticipatory Planning for Sea-Level Rise Along the Coast of Maine. In EPA (Ed.), Policy, Planning, and Evaluation.

Urban Land Institute. “Waterfronts of Portland and South Portland Maine.” In A ULA Advisory Services Panel Report, edited by James A. Mulligan. Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 2014.

U.S Census., Data, 2014

Final Research Paper for Karl Reinhardt

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Final-Paper-Reinhardt.docx”]

Bus data collection

Early Warning Weather System

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Early-Warning-Weather-Sensor-System-Portland-small.pdf”]

Security in Portland as a Smart City

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/NDiaye_finalPaper_Part11.docx”] [gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/NDiaye_FinalPaper_Part21.docx”] [gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/NDiaye_FinalPaper_Part3.docx”]

Improving Portlands Public Bus System – Final Research Paper

Improving Portland’s Public Bus System

Konstantine Mushegian

The Digital Image of the City – INTD2430

Professor Jen Jack Gieseking

Abstract

This paper addresses the issue of public transportation in Portland, Maine and offers smart city solutions and policy recommendations that will improve the existing transit system. Technological solutions and policy recommendations proposed at the end of this paper will aim to reduce commute times through the intelligent bus stop placement. Optimal bus stop locations will reduce the average walking time to the bus stop, thus making the public transportation system more accessible and attractive for residents and visitors alike. Portland’s Comprehensive Plan website has only one document that addresses the issues of public transportation in and around the City of Portland. “A Time of Change: Portland Transportation Plan” was proposed to the City Council in July of 1993 by a “Committee of Citizens” [1] but the majority of issues brought up in the plan still seem to exist, almost twenty-two years later. The plan to overhaul Portland transit system that was put together by citizens addresses and tackles issues of intra- neighborhood and inter-neighborhood transportation but no significant changes have been made since 1993. The fact that nothing of importance has been changed is also reinforced by the fact that the only document on the Comprehensive Plan website that touches upon the issues of public transportation is from 1993. I have been regularly reading the minutes from the meetings of the Portland City Council Committee on Transportation, Sustainability and Energy (TSE) for the past couple months. The issue of bus stop placement was brought up at the TSE meeting on September 27, 2014 and a request for proposals was issued in the same month for a Hub Link Feasibility Study in order to “evaluate feasibility of transit routes which will best improve connections between local and regional transportation terminals and major points along the corridors connecting them”[2] but no proposals were received by the deadline of October 17th.

The lack of proposals indicates the inactivity and nonchalance of residents and commuters who are affected by the issue the most. In addition, I will also offer suggestions on how to improve citizen involvement in public issues in this paper.

Continue reading Improving Portlands Public Bus System – Final Research Paper

Rebuilding and Reutilization: Revitalization of Portland Piers

https://drive.google.com/folderview?id=0B2vvrbJ-N-zDUE5UQksxMFNXZUk&usp=sharing

Rebuilding and Reutilization: Revitalization of Portland Piers

Research Topic

This paper argues that one of the most crucial and feasible infrastructure projects for the City of Portland, Maine, is the rebuilding, repurposing, and ultimately the revitalization of piers in the Downtown or “Old Port” district. The utilization of the piers through the development of public green space (a “pier park”), and residential and commercial real estate would have the most direct economically and socially beneficial impact on the city, specifically the Old Port. I propose redeveloping the properties into multiple public and private spaces with the intention to alleviate the concerns of a lack of public space and underutilized valuable waterfront real estate. This paper argues that the implementation of technologically forward-thinking power systems as well as data collection and monitoring systems will push Portland into the “Smart City” era. Portland has recently revamped its rules and regulations regarding the existing piers, and several businesses have capitalized on the exclusive real estate, but much more needs to be done to complete the transformation of Portland’s Old Port piers.

Approach to the common good for the city

The piers of the Old Port are some of the most feasible locations to implement changes benefitting the common good, due to their current run-down condition and proximity to the highly trafficked and desirable commercial region of the Old Port. The proximity of the piers to the burgeoning and gentrifying neighborhoods of downtown Portland promises increased public demand and economic investment. The redesign of the piers as an extension of the existing waterfront park system, new housing development, and business and restaurant center would directly benefit the Common Good by encouraging physical wellness and economic development. The new pier park would be a resource for free physical (and subsequently emotional) wellness to all visitors. Office space, restaurants, and retail shops would build the local economy, due to the piers’ proximity to the downtown neighborhoods and business district of Portland. Currently, however, they offer no access, claim, change, or ownership to those of lower classes.[1] A seafood market, arguably pricey, and a high-end tote bag shop were noteworthy businesses currently inhabiting one pier. Another pier has only a few pricey apartments. My proposed plan would at least extend the rights of access and wellness for those less privileged.

Approach to the smart city

Sensors and networks of sensors are a “key requirement for the delivery of Smart Environments”, but they are disruptive to install on existing systems/buildings.[2] Powerwise Systems, a Maine business, was started specifically to produce the types of sensors and monitoring equipment able to be installed into pre-existing infrastructure. The systems provide “circuit-level electrical monitoring; remote HVAC and lighting controls; building environment monitoring; performance measurement for PV, solar thermal, heat pumps, energy-recovery ventilators (ERV/HRV); and a variety of flow, fluid level, water, and gas monitoring.”[3] Access to this knowledge would encourage less wasteful behavior, thereby creating a healthier environment and benefiting the common good. It seems obvious that, with these systems already designed and able to be easily installed, the City of Portland should invest in systems. The systems should be installed in City buildings; businesses can nail down machines, practices, or groups that are particularly inefficient; landlords can pinpoint wasteful renters, and even specific rooms that need work; and individual homeowners can control their living spaces from-away to minimize their effect on the environment and the strain on their wallet. The rapid progression of technology is now making it possible to control and monitor these systems from a mobile device, encouraging around-the-clock watchfulness and accountability. However, with a newly installed Powerwise monitoring system comes large-scale data collection and analysis. According to Crowley, Curry, and Breslin, data aggregation from separate existing public systems is a logistical nightmare.[4] In addition, data analysis of citywide, national, international, or global data sets is a monumental task requiring lots of time on specialized high-computing systems run by data and statistical specialists.[5],[6] Ultimately, this means that the tremendous amount of data produced by the system of sensors will need to monitored for specific measurements, trends, or anomalies, with the caveat that much of the generated data from these sensors will go unused for years before computing power rises to levels able to handle current and past data simultaneously.

Literature review

There has been much discussion around the topic of redeveloping and reutilizing existing infrastructure, a small selection of which I will touch on in this short proposal. In his essay “Traffic in Democracy”, Michael Sorkin describes the American growth ideal of “sprawl without end” as having “escaped rational management.”[7] The Downtown of Portland has a different problem, however; located on a peninsula, sprawl and outward growth are not possible. In this case it becomes crucial either to build up, as most large cities opt for, or to repurpose existing infrastructure. This paper points to the London Docklands and New York City’s Hudson River Park as two notable examples of rebuilding, reutilization, and, ultimately, revitalization.

In NYC it is clear that space limitations drove development up; but NYC was obsessed with “NEW, BETTER, DIFFERENT!” Portland and many other cities don’t have the capital, capabilities, or desire to follow that building plan, and should think instead about how to reuse existing infrastructure. Hudson River Park in NYC has been heralded as “the model for New York City parks to come” and “the most significant new public space since Central Park.”[8],[9] Built out of the failed Westway highway project, development of the park was started in 1998 and is approximately 70% complete today.[10] Transformed from decaying piers and parking lots, it is the second largest park in the city after Central Park, encompassing 550-acres and offering over thirty different activities.[11] It is also the largest waterfront park in the United States and hosts 17 million visitors annually.[12]

The Docklands in the outskirts of London were “the old spaces, liberated from their traditional activities and lying derelict and unwanted, [that needed to] be recycled to meet the needs of the new economic world.”[13] Slow abandonment after changes in shipping vessel size rendered the docks obsolete; it took tens of years, millions of dollars, and a bevy of government and public groups to rebuild and revitalize the Docklands. The region now houses the “engine-rooms of twenty-first century business.”[14] In fact, due to the many banks and other economically important businesses in the area, Canary Wharf now rivals London as a financial stronghold.[15],[16] The current economic importance of the Docklands, the region’s architectural transformation from rough industrial and manufacturing buildings to clean-cut skyscrapers of international business, and the discovery of the necessity of cooperation has made the 30-year development a case study of urban revitalization. Against all odds, the London Docklands “wasteland” has become a “Wall Street on Water.”[17]

Setha Low argues that the privatization and commercialization of public spaces is necessary to their future and points out that they induce an expected level of class in the public space.[18] By allowing more non-marine groups and providing economic incentives for businesses, Portland could also develop the piers into an exceptional extension of the already existing waterfront park system. While this privatization may seem to subvert the “right to the city” as Lefebrev puts it, or “the right to sleep unmolested in a city park”, as Mitchell suggests, I argue that the piers as they now stand offer even less right to the underprivileged.[19] In their current ramshackle state, the piers are targets for tighter scrutiny and do not allow public access, excepting the road, thereby making it difficult for the underprivileged to access the waterfront or stake any claim in the space. By creating a public green space and improving the overall conditions of the piers, Portland simultaneously will provide an opportunity for the “right to the city”.

Rebuilding infrastructure requires more than clever engineering as Michael Sorkin tells us in his essay “Traffic in Democracy”: “It has to be thought through politically… rather than approached as merely a set of technical problems.”[20] Since the 1980s when condominiums were built on Chandlers’ Wharf in the Old Port, city policy has restricted development and occupancy to a working waterfront. However, given recent policy changes allowing “up to 45 percent of the ground floor to… non-marine tenants”, the door is slightly more open for other offices and businesses to move into these prime waterfront locations.[21] These business opportunities should be quick to be filled, but the marine spaces remain available due to a deflating ecosystem and therefore decreasing numbers of fishermen and other traditional Maine marine business. Fortunately, there is business called the New England Ocean Cluster proposed on the neighboring Maine State Pier that would fit the marine requirement and greatly benefit the region.[22] While this business would be a great boon for the piers and the City, this is only one of many available marine spaces, and much more needs to be done to complete the transformation of the piers. Ultimately, the redevelopment of the piers as public green spaces, as well as business and housing options, is the most feasible and natural next step in the growth of Portland and will be supported by a history of similar projects around the world.

Methods

My methods of collecting data were threefold: First, data was collected on the revitalization of old buildings during a transect walk. Any structure that appeared to have an authentic skeleton or base, but with obvious new construction or renovations was marked on Map 1. Structures varied from residential-to-business converted properties to unintended utilization of old building space. I chose not to walk in the commercial section of the Old Port because this type of reutilized building structure (store or restaurant at ground level with apartments above) is very common. These streets have been distinguished on the map as generally well-repurposed and revitalized areas.

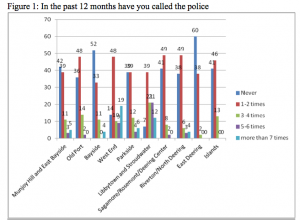

Second, every member of the Digital Image of the City class collected mental map data from Portland residents and commuters. The compiled mapping data provided a lens into the perceived needs of people of Portland as seen in Figure 1. The first part of the figure shows the distinct mentions of green space, waterfront access, economic incentives, art/music spaces, and the preservation of old buildings as a measure for possible resident interest in a proposed pier renovation and revitalization project. Additionally, the second part of the figure shows the prevalence of the geographic areas around the piers on mental maps.

Third, commercial real estate data and residential real estate data was scraped from loopnet.com and zillow.com, respectfully, to build a database of commercial and housing prices in the Downtown. Visualizing this data shows the economic benefit of a water view and real estate closer to the water, as evidenced in Map 2, and the lack of available residential real estate, as evidenced by Image 1. Additional geographic data on green space from the City of Portland allowed the creation of Map 3, which demonstrates the need for the continuation of the waterfront park system. The map displays the green spaces with a buffer zone of five hundred meters, or about one-third of a mile, a comfortable walking distance for any age.

Findings

There is a clear need for these developments, as evidenced by comments from two mental map participants; one participant suggested “Preservation of old buildings – redevelop for business and residency”, while another participant suggested “[Affordable] underground/young spaces for activism and art” and “public meeting spaces for groups/bands.”[23] I found that most of the spaces I saw on my transect walk were restaurants and businesses that necessitated redesigned spaces. I also found that many houses on the Eastern Prom have undergone repairs to make the expensive houses worth more as multiunit apartments or condos. In addition, the fact that the real estate data demonstrated an increasing cost of commercial spaces close to the water implies a desire for office and business spaces, just as the lack of available residential real estate suggests competitive desirability and the need for more spaces. Finally, the proximate green space allows one to visually understand the necessity for a waterfront recreation area, extending the existing park system along Back Bay and the Eastern Promenade.

Reflections/discussion

Portland is a city that likes to stick with its heritage and is restricted by space limitations, but yearns to progress into the future. Repurposing buildings is a fantastic and fascinating use of existing infrastructure because it requires fewer materials and creates less waste, while revitalizing the look (and often purpose) of the building. I propose transforming Portland Pier, Custom House Wharf, and 68 Commercial Street pier, three run-down, mostly dilapidated piers into public green space and commercial and residential real estate. In the beginning of Against the Smart City, Greenfield directly states that the way “city dwellers collectively understand, approach and use the environment around us” is rapidly changing.[24] Even though there have been issues in the past with new condos on the water, we now know the allure and value of those properties. Following the examples of the Hudson River Parkway in New York City and the

|

London Docklands, we know the project is feasible.

As evidenced by Map 1, proximity to highly trafficked roads, retail and restaurant venues, and water views are large influencers of revitalization. It makes sense to continue the revitalization and reutilization of the Old Port on the piers because the underutilized space currently serves very few people and purposes, and provides very little economic benefit for the City, but has the potential for fantastic success, given the piers’ proximity to the commercial and restaurant district. Therefore, I propose the repurposing of commercial and residential buildings, and development of public green spaces, as a method for economic and infrastructure revitalization.

Figure 1 demonstrates the potential support for my proposal, as measured by residents’ specifically voiced concerns in interviews and noted locations on their mental maps. Fifteen of the one hundred residents specifically and uniquely pointed out one of the categories my proposed pier revitalization project would address, namely access to green spaces and the waterfront, economic incentives for businesses, spaces for art and music, and the preservation of old buildings. Exactly half of the residents interviewed chose to note the waterfront as an important feature of Portland on their mental map, while slightly more than one-fourth mentioned the Old Port/Downtown and/or the main waterfront street of the Downtown, Commercial Street. These responses indicate a strong level of interest and motivation by

|

Portland residents to enhance the Downtown and waterfront areas.

As seen in Map 2, there is clear economic benefit of water views and lower Downtown real estate in Portland for office and retail spaces. This data suggests the potential economic benefit of new real estate development on the piers, with leasing prices upwards of $30 per square foot. A rough estimate of the area of the three piers is 280,000 square feet. Assuming one-quarter of the pier is used for commercial real estate, there are two floors in the building, and an average price of $30 per square foot yields a conservative estimate of $4.2 million in taxable leasing revenue per month. This figure does not even take into account the revenue generated by those businesses and their employees eating or shopping at other nearby businesses, a further

|

infusion of hundreds of thousands of dollars into the local economy.

|

Image 1 expresses a lack of residential real estate in the Downtown, and shows that the rental prices are comparable to elsewhere in the city. As the city continues to gentrify and the price of housing continues to rise, there will be an increased demand for housing options, especially in close proximity to areas of employment. The piers provide an optimal opportunity to nip this situation in the bud. With their relative proximity to the majority of commercial and business jobs in the City, and available floor space for housing, the piers offer a solution to Portland’s expanding working population. An estimation of monthly taxable residential real estate (assuming one-quarter of the pier, two floors, at an average rental rate of $2,500 per month per 1,400 square feet) yields $250,000 in taxable revenue every month, and doesn’t take into account the hundreds of thousands of dollars spent locally in the Downtown by residents of the real estate.

|

As evidenced by Map 3, there is a need for additional green space in the Downtown to allow access to the waterfront, provide pleasurable public space for visitors and citizens, and enhance the value of surrounding buildings. In pink is the Downtown area of Portland that is not within 500 meters of a public green space and the proposed revitalized docks are in yellow. While understanding that creating public space has no direct economic benefit for the City, there are clear correlations between access to open, natural space, including a pleasurable waterfront, and workplace productivity and community happiness and health.[25], [26], [27] Additionally, creating a new public space would require vacant land, not often available in the City, especially in residential neighborhoods. Therefore, it would benefit all local businesses, residents, and the common good of the City to continue the already existing and well-used bike path and public green space along the waterfront, while utilizing the currently vacant pier land.

With the assistance of the Portland City Council and public support, one may be able to make the case for a non-typical marine institution such as an aquarium or seafood restaurant, or a space capitalizing on the water and benefiting the common good such as a park and ice rink to inhabit the lesser-used marine 55 percent. This policy change may be a make-or-break factor in the reutilization of the piers, since the existing policy makes it very difficult for all the available land to be utilized to its full economic and common good potential.

Policy Recommendation

My policy recommendation for the city of Portland is threefold. First, amend the current 45-55% (general – marine) space use policy to include non-traditional marine uses over the entire pier system, instead of on individual piers or real estate blocks. Second, encourage economic investment in the physical infrastructure of the piers with tax incentives for repurposing the existing structure. And third, designate and mandate public green space on the piers to encourage residential and tourist interaction with the waterfront. By employing these policy recommendations, the City of Portland will create a new dimension of The Old Port filled with benefits for the local economy and common good.

Conclusion

The Old Port has a fantastic resource within its grasp. There is demonstrated optimistic public interest, positive economic value, a rich history of reutilization in the City, and public health and wellness benefits. In addition, there are a number of prominent success stories from other cities off which to base plans and gain knowledge. The City of Portland should redouble efforts to reutilize the Portland Pier, Custom House Wharf, and 68 Commercial Street pier as sites of residential and commercial real estate and public green space for the benefit of the local economy and common good

Bibliography

Bagli, Charles V., and Lisa W. Foderaro. “Times and Tides Weigh on Hudson River Park.” New York Times, January 28, 2012.

Bell, Tom. “Maine State Pier envisioned as site of incubator for marine businesses.” Portland Press Herald. Last modified October 17, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/10/17/maine-state-pier-envisioned-site-incubator-marine-businesses/.

Billings, Randy. “New Building on Maine Wharf Reflects Portland’s Changing Waterfront.” Portland Press Herald. Last modified August 7, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/08/07/new-building-other-progress-reshape-portlands-waterfront/.

“The Changing Face of London: London Docklands,” September 2012. http://bbc.com.

Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, edited by Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre, 380-82. N.p.: Springer, 2014.

Frumkin, Howard, and Richard Louv. “The Powerful Link Between Conserving Land and Preserving Health.” Editorial. Children & Nature Network. Last modified July 1, 2007. http://www.childrenandnature.org/news/detail/the_powerful_link_between_conserving_land_and_preserving_health/.

Gillett, Rachel. “How to Stop Your Office From Zapping Your Productivity.” Fast Company. http://www.fastcompany.com/3029994/work-smart/how-to-stop-your-office-from-zapping-your-productivity.

Greenfield, Adam. Against the Smart City. 1.3 ed. N.p.: Do Projects, n.d.

Hall, Peter. “The City of Capitalism Rampant.” In Cities in Civilization, 888-929. New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1998.

Hannah, and Joyce. Interview by the author. Coffe By Design, India Street, Portland, ME. October 2014.

How We Built Britain. “The South: Dreams of Tomorrow.” BBC. November 2012 (originally aired July 2007).

Hudson River Park Trust. “About Us | Hudson River Park.” Hudson River Park. Accessed September 2014. http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/about-us.

———. “Explore The Park.” Hudson River Park. http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/explore-the-park.

———. “Hudson River Park Act.” Hudson River Park. http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/about-us/hrpt/hrp-act.

“InView Building Monitoring and Energy Management Solutions.” PowerWise Systems. http://www.powerwisesystems.com.

Ivy, Robert. “Waterborne City.” Abstract. Architectural Record, October 2009.

Low, Setha M. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 164. New York, NY: Routledge, 2002.

MacLeod, Alexander. “Wall Street on Water: The Rebirth of London’s Historic Wharfs.” Christian Science Monitor, November 19, 1997.

Mayer-Schönberger, Viktor, and Kenneth Cukier. Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013.

Mitchell, Don. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights, and Social Justice.” 2003. In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, 193-94. New York, NY: Routledge, 2014.

Price-Mitchell, Marilyn, Ph.D. “Does Nature Make Us Happy?” Psychology Today. Last modified March 27, 2014. http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-moment-youth/201403/does-nature-make-us-happy.

Silver, Nate. The Signal and the Noise: Why so Many Predictions Fail–but Some

Don’t. New York, NY: Penguin, 2012.

Sorkin, Michael. “Traffic in Democracy.” 1999. In The People, Place, and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, 411-15. New York, NY: Routledge, 2014.

[1] “About Us | Hudson River Park,” Hudson River Park, accessed September 2014, http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/about-us.

[2] David N. Crowley, Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin, “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments,” in Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, ed. Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre (n.p.: Springer, 2014), 380.

[3] “InView Building Monitoring and Energy Management Solutions,” PowerWise Systems, http://www.powerwisesystems.com.

[4] Crowley, Curry, and Breslin, “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap,” in Big Data and Internet, 382.

[5] Viktor Mayer-Schönberger and Kenneth Cukier, Big Data: A Revolution That Will Transform How We Live, Work, and Think. (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013).

[6] Nate Silver, The Signal and the Noise: Why so Many Predictions Fail–but Some Don’t (New York, NY: Penguin, 2012).

[7] Michael Sorkin, “Traffic in Democracy,” 1999, in The People, Place, and Space Reader, ed. Jen Jack Gieseking (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014), 412.

[8] Robert Ivy, “Waterborne City,” abstract, Architectural Record, October 2009, 25.

[9] Charles V. Bagli and Lisa W. Foderaro, “Times and Tides Weigh on Hudson River Park,” New York Times, January 28, 2012.

[10] “Hudson River Park Act,” Hudson River Park, http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/about-us/hrpt/hrp-act.

[11] “Explore The Park,” Hudson River Park, http://www.hudsonriverpark.org/explore-the-park.

[12] “About Us | Hudson,” Hudson River Park.

[13] Peter Hall, “The City of Capitalism Rampant,” in Cities in Civilization (New York, NY: Pantheon Books, 1998).

[14] How We Built Britain, “The South: Dreams of Tomorrow,” BBC, November 2012 (originally aired July 2007).

[15] “The Changing Face of London: London Docklands,” September 2012, http://bbc.com.

[16] How We Built Britain, “The South: Dreams of Tomorrow.”

[17] Alexander MacLeod, “Wall Street on Water: The Rebirth of London’s Historic Wharfs,” Christian Science Monitor, November 19, 1997, 10.

[18] Setha M. Low, “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza,” in After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, ed. Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin (New York, NY: Routledge, 2002), 164.

[19] Don Mitchell, “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights, and Social Justice,” 2003, in The People, Place, and Space Reader, ed. Jen Jack Gieseking (New York, NY: Routledge, 2014), 193-194.

[20] Sorkin, “Traffic in Democracy,” in The People, Place, and Space, 412.

[21] Randy Billings, “New Building on Maine Wharf Reflects Portland’s Changing Waterfront,” Portland Press Herald, last modified August 7, 2014, http://www.pressherald.com/2014/08/07/new-building-other-progress-reshape-portlands-waterfront/.

[22] Tom Bell, “Maine State Pier envisioned as site of incubator for marine businesses,” Portland Press Herald, last modified October 17, 2014, http://www.pressherald.com/2014/10/17/maine-state-pier-envisioned-site-incubator-marine-businesses/.

[23] Hannah and Joyce, interview by the author, Coffe By Design, India Street, Portland, ME, October 2014.

[24] Adam Greenfield, Against the Smart City, 1.3 ed. (n.p.: Do Projects, n.d.)

[25] Rachel Gillett, “How to Stop Your Office From Zapping Your Productivity,” Fast Company, http://www.fastcompany.com/3029994/work-smart/how-to-stop-your-office-from-zapping-your-productivity.

[26] Marilyn Price-Mitchell, Ph.D., “Does Nature Make Us Happy?,” Psychology Today, last modified March 27, 2014, http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-moment-youth/201403/does-nature-make-us-happy.

[27] Howard Frumkin and Richard Louv, “The Powerful Link Between Conserving Land and Preserving Health,” editorial, Children & Nature Network, last modified July 1, 2007, http://www.childrenandnature.org/news/detail/the_powerful_link_between_conserving_land_and_preserving_health/.

Providing Access to Public Wi-Fi and Computers: A Two-Step Proposal to Ensure Portland’s Continued Success in the Digital Age

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Providing-Access-to-Public-Wi-Fi-and-Computers.pdf”]