[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/Final-paper.pdf”]

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Unaffordable Housing: Preempting Displacement and Preparing Low-Income Renters

[gview file=”https://courses.bowdoin.edu/digital-computational-studies-2430-fall-2014/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2014/12/bmiller_DIOTC_affordable.compressed.pdf”]

Hannah Rafkin

The Digital Image of the City

Professor Jen Jack Gieseking

12/17/14

BoostPortland: Grappling with Homelessness in the Smart City

Research Area

In the United States, national homelessness declined by over 9% from 2007 to 2013. In the state of Maine, homelessness increased by 17% from 2009 to 2013. In the same timespan, homelessness has increased by 70% in the city of Portland, growing at four times the rate of the state. [1] The city is well known for its extensive support infrastructure, particularly Preble Street Resource Center. Preble Street has been extensively hailed for its “housing first” model, in which people are given housing regardless of substance abuse or mental health problems. Despite the excellence of Portland’s resources for the homeless, these centers are overwhelmed. Shelters often have spillover, leaving many people curling up on chairs or on the floor, oftentimes in other facilities. One cold night in 2013, only 272 shelter sleeping spots were available for double the number of people who sought them out. [1]

The Task Force to Develop a Strategic Plan to Prevent & End Homelessness in Portland reported on the demographics of Portland homelessness as of 2012. The average age of a shelter-goer was 40. Nearly 60% faced mental illness, and nearly 38% grappled with drug addiction – 70% reported a combination of the two. At Florence House, Preble Street’s housing unit for chronically homeless women, 66% were victims of abuse, 54% victims of domestic abuse specifically. Seventy one percent of homeless people had been homeless for a month or less. [2] According to a Bangor Daily News article, a third of homeless people in Portland’s shelters are from the city, another third are from other Maine towns, and another third are from out of state. [3]

Policy Controversies

The City Council of Portland discussed extensive plans to address these issues in the same 2012 report. Their goals included “Retooling the Emergency Shelter System, Rapid Rehousing, Increased Case Management, and Report Monitoring.” Specifically this meant creating a centralized and streamlined intake and assessment process, developing additional housing units, increasing rental opportunities, working with landlords to make housing more accessible, adopting and enhancing an ACT (Assertive Community Treatment) case management system, and increasing work and educational opportunities for homeless youth, families, and veterans. [2]

The Portland Chamber of Commerce responded negatively to the task force and the presence of the homeless population more generally, wondering if the city of Portland was “too attractive to the homeless.” [3] The president of the Downtown District said the homeless were “intimidating,” and “hurt [Portland’s] ability to be a tourist destination and also our business.” [4] The Chamber expressed concern that the city was becoming “a disgusting filthy mess.” [3] Mark Swann, director of Preble Street Resource Center, was “deeply saddened and disappointed by…the misguided and mean-spirited comments…Dehumanizing our neighbors struggling with poverty, homelessness and hunger is deplorable.” He advised the Chamber to talk with Preble Street’s councilors to get a better sense of the “attractiveness” of homeless life in Portland. [4]

These contrasting attitudes represent a growing tension in Portland between wealthy gentrification and impoverished homelessness. As homelessness has skyrocketed in recent years, the city has become increasingly trendy – ‘hipster’ cafes, pricey shops, and condos-with-a-view have sprung up incessantly. Swann’s suggestion for conversation between the Chamber and the Resource Center is wise – these seemingly opposing forces could benefit from dialogue instead of distant and impassioned resentment.

I observed this conflict of interests in action during my transect walk through Portland, noticing the strained simultaneity of homelessness and gentrification. I was particularly struck by a juxtaposition I observed at the busy intersection of Franklin Street and Marginal Way. A homeless man stood leaning against a road sign, holding up a flimsy piece of cardboard. Yards away was a store called Planet Dog, catering exclusively to the bedding, food, toys, and accessories of Portland’s canines. An astronomically expensive antique shop and a home entertainment center sat down the road from Preble Street Resource Center.

Later on, another juxtaposition presented itself. I was walking through Congress Square Park taking photographs and surveying the scene. Some people sat on the steps, one man grilled burgers, another played guitar. My taking pictures clearly upset a woman sitting on a bench, who got up and followed me for several blocks, slurring and staggering, yelling “Fuck the white house, bitch” and other obscenities. Nonsensical as the specific expression of her outrage may have been, this encounter was representative of a larger urban tension. I am a white girl from New Jersey, doing coursework for a course at an elite college, wielding an imposing SLR camera in the attempt of ‘capturing the city,’ only visiting for a brief and comfortable afternoon of exploration. In that instance, I was encroaching on her space – she does not have the option to ‘explore’ the city lightheartedly.

Layers of Congress Square Park

Boost Portland – Smart City Solution

A man I interviewed outside of Preble Street said that complications of daily life and a lack of affordable housing make it “impossible for people to get on their feet” in Portland. I propose a combined application, website, and texting service called BoostPortland, aimed to get Portland’s at-risk population on their feet – and to keep them on their feet – by meeting everyday, individualized needs beyond sleep and food. BoostPortland will draw on the city’s own residents, businesses, and organizations to to support the city’s neediest citizens, creating a pervasive network dedicated to bettering their community. BoostPortland will provide a platform for the struggling citizens of Portland to receive help in confronting the myriad challenges of daily life.

Users would create posts, either offering or seeking out assistance. An individual could post offering help with resumes at the public library, advertising an odd job like shoveling a driveway, or giving away clothing items. Somebody could post requesting a ride to a job interview, asking for a winter jacket, or seeking help with English. Businesses could post offering free food, wireless Internet, a space to organize, or perhaps just some time to warm up.

This format allows for direct and impactful volunteerism on the terms of both the giver and the receiver. Specific, attainable needs will be met at a convenient time and a convenient place for both parties, while creating connections between Portlanders of varied backgrounds. Additionally, involving a diverse group of businesses – from Salvation Army to Portland Architechtural Salvage – might help to ground them in the often-grim realities in the city. This might give them a better understanding of the challenges facing the homeless population, and allow for increased awareness of the role of commerce in making Portland an increasingly expensive place to live. Ideally, businesses will then reconsider the sentiments expressed by the Chamber of Commerce in response to the task force.

Approach to the Common Good for the City

Urban centers are hotbeds of diversity. Socioeconomic, racial, cultural, sexual, and lifestyle differences guarantee exposure to fresh perspectives. In a city with a focus on the common good, all perspectives are given a voice, and there exists a platform for productive and engaging “encounter and exchange.” [5] In a city with a focus on the common good, all citizens have access to basic human rights – water, food, and shelter are attainable for everyone. In a city with a focus on the common good, there is a network of organized care and action around issues of social justice impacting the city.

The homelessness task force is on the right track to meeting this definition (though its website’s most recent agenda item is dated October 11, 2012) but the Chamber of Commerce’s focus on business and tourism poses roadblocks in attaining the common good in Portland.

Approach to the Smart City

The ambitious and futuristic proposals to re-envision the technological functioning of the modern day city in “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments” are exciting. [6] But the idea of “everything [becoming] a sensor” is perhaps overzealous, and has major potential to verge into Big Brother territory. [6] The focus on using technology to better conserve energy is very appealing, however.

A truly smart city integrates technologies that are “situated in a specific locale and human context,” as described by Adam Greenfield. [7] South Korea’s city of Songdo exemplifies the pervasiveness of technology described in Crowley, Curry, and Breslin’s article, but lacks contextual concern for the interests, behaviors, and problems facing its citizens. Songdo was built before those interests, behaviors, and problems could even manifest, before city planners could consider how their innovations would function within the specific flow and feel of the city. In the smart city, citizens define the technology; the technology does not define the citizens.

As technologies tend to be expensive, they come with concerns of accessibility. The smart city does not limit its innovations to “those who can afford it and conform to middle-class rules of appearance and conduct.” [8] This notion is particularly pertinent to my research area.

Literature Review

“To Go Again to Hyde Park” by Don Mitchell emphasizes each citizen’s “right to the city,” though those rights are not always made equal in practice. [5] As “some members of society are not covered by any property right,” they must “find a way to inhabit the city…as with squatting, and with the collective movements of the landless, to undermine the power of property and its state sanction, or otherwise appropriate and inhabit the city.” [5] Mitchell advocates for the marginalized populations’ participation – forcefully, if need be – in the dialogue of urban life. In “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space,” Dolores Hayden also stresses the importance of undervalued voices in urban conversation. She discusses the development of the urban landscape, describing the role of every inhabitant of a city, the marginalized included, in shaping its look, feel, and experience: “Indigenous residents as well as colonizers, ditchdiggers as well as architects, migrant workers as well as mayors, housewives as well as housing inspectors, are all active shaping the urban landscape.” [9]

Technology continues to reform the way citizens interact with each other and share ideas, even within disenfranchised populations. The homeless community’s usage of cell phones has skyrocketed in recent years. In 2009, advocates from Washington D.C. estimated that 30%-45% of the homeless population they worked with owned cell phones. [10] In a 2010 study of homeless cell phone use in Philadelphia, 44% of a 100-person sample size owned cell phones. [11] A 2013 study found that 70.7% of Connecticut homeless emergency room patients owned cell phones. [12] No such study exists for Portland, but similar patterns likely apply. As the homeless population becomes increasingly technologically active, a solution like BoostPortland gains potential to foster discussion and exchange between the haves and have-nots of the city, drawing on the broader community to improve the lives of Portland’s neediest citizens.

Integrating technology into such projects must be done thoughtfully, however. At a 2012 technology conference in Austin, Texas, a marketing agency proposed that homeless people be utilized as mobile wireless Internet transmitters. For $20 a day, homeless people walked around wearing shirts that said “I’m _____, A 4G Hotspot.” Instead of creating inclusive dialogue, this “charitable experiment” denied the personhood of the participants, defining individuals only by their potential for beneficial functionality. One blogger aptly described the project as “something out of a darkly satirical science-fiction dystopia.” [13]

The Hack to End Homelessness meet up in Seattle provides a better model for conscientious use of technology – developers, designers, and “do-gooders” got together to brainstorm solutions for homelessness. The event produced exciting data, maps, applications, and other programs with a focus on dialogue between groups with different staked interests – the event organizer foregrounded the importance of “[reducing] tension between the housing community and tech workers.” [14]

Methods

Representing the homeless through maps was a difficult undertaking – without an address, homeless citizens do not get represented in government census data. Data about issues surrounding homelessness exists (housing, income, neighborhoods). Social Explorer median income census data and the ‘PlanNeighborhoods’ Portland Shapefile were particularly helpful in establishing a backdrop for new data about homelessness directly.

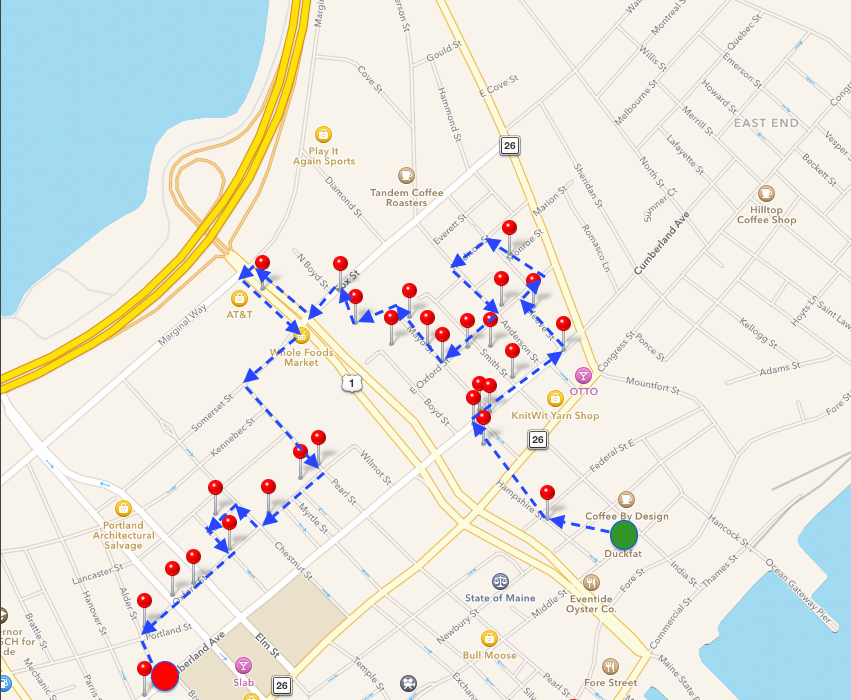

I created new data sets on Portland’s homeless encampments, resource centers, and affordable housing. I began by geocoding the addresses of all of the homeless encampments mentioned in the Portland Press Herald in the past three years to get a sense of where the homeless are congregating. Then, I placed these data points on top of median income data to juxtapose the temporary homes of the homeless with the financial context of their temporary surroundings. This layer provides a means of accounting for transient homes of those that the census does not count – an attempt to bring the homeless onto the city map. I also geocoded all of Portland’s resource centers, shelters, and soup kitchens, and placed them on the same map as the encampments to see where help is concentrated in the city and where it is lacking. As the dearth of affordable housing has made living a stable life in Portland increasingly difficult, I was curious about the prevalence and whereabouts of existing affordable housing in the city, so I mapped housing units deemed affordable by the Maine State Housing Authority. [15]

Findings

As the above map demonstrates, the homeless are inclined to camp near the water and in wooded areas. They camp mostly in low- to middle-income regions, though not exclusively. The city’s resource centers are mostly concentrated in a small pocket in Bayside, a low-income region of Portland. The encampments and resource centers do not show significant overlap in location.

The above map shows that housing deemed affordable by the Maine State Housing Authority is centralized in the Downtown, Bayside, and East End regions of Portland. It is interesting and concerning to consider the consequences of sectioning off low-income populations, reminiscent of tenement-style urban layouts that Hayden discusses in “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” [9]

Reflections: Technological Concerns

BoostPortland will have three technological components to support the expected range of socioeconomic backgrounds: a smartphone application, a website, and an SMS texting service. The smartphone application will likely appeal to a more economically stable faction of users, as they are more likely to own them. It will have a simple and clean interface. There will be four tabs: Get Help, a list of the day’s offers, Give Help, a list of the days requests, Map, a map version of both lists, and Post, an interface for users to offer or request assistance. Users can click on an offer or a request for more details, linking to contact information of the poster. The website will be structured identically. The SMS service will allow those with basic cell phones to request or give assistance on the move. Users can text in requests or offers, to be added to the daily lists. Users can also subscribe to a daily text containing one or both lists, and can text in a reply to be put in contact with the giver or receiver of help.

This technology-driven idea of a combined application, website, and texting service – aimed to assist Portland’s most disenfranchised population – comes with obvious challenges. Without such basic amenities as consistent shelter or food, the homeless and impoverished are much less likely than the average Portlander to have access to such technologies. However, homeless people nation-wide are becoming increasingly technologically connected, as shown by the aforementioned studies on homeless cell phone use in Washington D.C., Philadelphia, and Connecticut. With these changes, homeless people will have increasing accessibility to solutions in the form of apps and websites, and especially basic SMS texting. This is particularly true of homeless youth and the recently homeless, as noted by Mark Swann, director of Preble Street. Additionally, Preble Street and the Portland Public Library have free computers where users could access the website component of BoostPortland.

Policy Recommendation

Portland’s homelessness task force has laid out some very important goals. I suggest that the City Council involves the Chamber of Commerce in achieving them to augment the city’s response to homelessness. Getting businesses involved in the issue will give them a broader understanding of what is happening to the marginalized populations in the city. This approach will also give the Council more power and leverage in addressing their goals, while creating productive dialogue between seemingly antagonistic forces, as Hack to End Homelessness sought to do. In light of the Chamber of Commerce’s commentary on the task force and, most likely, reticence to help, the City Council might create an incentive program to draw the Chamber to the Portland’s social justice issues.

Conclusion

BoostPortland foregrounds the voices of those in need by creating a communal network of Portlanders determined to face the growing problem of homelessness. By including local businesses and addressing gentrification head on, it has the potential to bridge the gap between monetary interests and humanitarian interests. I believe that this solution can make Portland a smarter, more connected, and more engaged city.

Works Cited

[1] Billings, Randy. “Homelessness Hits Record High in Portland.” Portland Press Herald. October 27, 2013. http://www.pressherald.com/2013/10/27/homelessness_hits_record_high_in_portland_/.

[2] “Report of the Task Force to Develop a Strategic Plan to Prevent & End Homelessness in Portland.” Portland City Council. November 16, 2012. https://me-portland.civicplus.com/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/Item/132?fileID=695.

[3] Koenig, Seth. “Is Portland ‘too attractive’ to homeless people?” Bangor Daily News. December 21, 2012. http://bangordailynews.com/2012/12/21/news/portland/are-cities-like-portland-too-attractive-to-homeless-people/.

[4] Murphy, Edward. “Preble Street Head Decries Chamber Remarks on Homelessness.” Portland Press Herald. November 16, 2012. http://www.pressherald.com/2012/11/16/preble-street-head-decries-chamber-remarks-on-homelessness/.

[5] Mitchell, Don. [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al. New York: Routledge, 2014)

[6] Crowley, David N., Edward Curry, and John G. Breslin. 2014. “Leveraging Social Media and IoT to Bootstrap Smart Environments.” In Big Data and Internet of Things: A Roadmap for Smart Environments, edited by Nik Bessis and Ciprian Dobre, 379–99. Springer.

[7] Greenfield, Adam. 2013. Against the Smart City. 1.3 edition.

[8] Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Micheal Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 163-72. New York: Routledge, 2014

[9] Hayden, Dolores. 1997. “Urban Landscape History: The Sense of Place and Politics of Space.” In The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History, 14-43. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

[10] Dvorak, Petula. “D.C. Homeless People Use Cellphones, Blogs, and E-Mail to Stay on Top of Things.” The Washington Post. March 23, 2009. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/03/22/AR2009032201835.html.

[11] Eyrich-Garg, Karin. “Mobile Phone Technology: A New Paradigm for the Prevention, Treatment, and Research of the Non-sheltered “Street” Homeless?” US National Library of Medicine. April 16, 2010. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2871091/.

[12] Eysenbach, Gunther. “New Media Use by Patients Who Are Homeless: The Potential of MHealth to Build Connectivity.” US National Library of Medicine. September 30, 2013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3786002/.

[13] Wortham, Jenna. “Use of Homeless as Internet Hot Spots Backfires on Marketer.” The New York Times. March 12, 2012. http://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/13/technology/homeless-as-wi-fi-transmitters-creates-a-stir-in-austin.html?_r=0.

[14] Soper, Taylor. “Hack to End Homelessness: Maps, Social Networks and Other Ideas to Help Seattle’s Homeless – GeekWire.” GeekWire. May 5, 2014. http://www.geekwire.com/2014/hack-end-homelessness-recap-maps-social-networks-startup-ideas/.

[15] “Cumberland County Affordable Housing Options.” Maine State Housing Authority. December, 2014. http://www.mainehousing.org/docs/default-source/housing-facts—subsidized/cumberlandsubsidizedhousing.pdf?sfvrsn=5.

Amending the Comprehensive Plan: A Study of Portland’s Recreational Infrastructure

Amending the Comprehensive Plan: A Study of Portland’s Recreational Infrastructure

Introduction and Research Question:

Portland, ME is a vibrant, diverse city in an easily accessible location only two hours north of Boston. As a major vacation destination throughout the summer, Portland places great value on its tourism industry. Healthy and vibrant cities must provide residents with proper infrastructure, namely the physical structures that make up the city, to support their and their primary industries. Portland’s infrastructure must support its tourism as well as its significant year-round population, 17.1% of whom are under the age of eighteen. As a substantial percentage of Portland’s population, school-age citizens have certain infrastructural needs that should be met by the city. Portland outlines certain policy goals in the city of Portland’s Comprehensive Plan including one stating that “recreational opportunities should be available for all ages and genders” and that “neighborhood open space should be within walking distance” for all residents. However, playspaces in Portland are not all easily accessible by children and do not serve children in all four seasons. For Portland to successfully meet its own goal of providing playspace infrastructure for its youngest citizens, it needs to provide more playspaces throughout the city, but also playspace infrastructure that is functional in multiple seasons and various weather conditions. I propose that Portland not only expand the number of playspaces in the city, but also create technology-controlled, weather-adaptable playspaces for children to use throughout all four seasons of the year.

Approach to the Common Good:

Residents in cities select a city in which to live for various reasons. However, one thing that all residents in any given city have in common is that together, they make up the living and breathing aspects of that city. Because of their proximity to restaurants, cultural hubs, and downtown areas, city residents often take for granted the variety of services and experiences to which they have access. There seem to be an endless number of perks to living in a city. However, many of these perks and services are expensive, and not all city residents are wealthy. Is a city truly accessible to all and benefitting the common good if it is not giving opportunities to all of its residents? While open park and recreation space is seen as a public good, it is often located in regions not easily accessible by lower socioeconomic classes. Further, playgrounds that do exist in lower-class neighborhoods are often dilapidated, run down, and known as dangerous locations after dark. In these circumstances, how can we create something that is accessible by all and for the common good? In my mind, children have a “right to play” similar to Henri Lefebvre’s “right to the city.” While the idea of creating something for the common good usually refers to the production of something that is entirely inclusive to all populations, children seem to have been vastly underserved in many other aspects of city planning in Portland, and therefore deserve to have something created specifically for them. If Portland as a city lists a policy goal relating to giving more of the population access to park and play space, then Portland needs to provide experiences for all, including the less wealthy and those without a vote: youth.

Approach to the Smart City:

One way in which a city can be characterized as a “smart city” is if aspects of the city are capable of adapting technology to fit the needs of the city. This could come to fruition in many ways. For example, this can be achieved with sensors that trigger changes in functionality of an office building depending on the number of people inside and whether they are working alone or collaboratively. The definition of a smart city varies depending on the goals of the project; they can benefit citizens economically, socially, politically, or culturally. There are also many methods by which a smart city can be created. Certain smart cities are built from the ground up; one example of this is Songdo, a city that is being developed as an “international business district” in South Korea. Other cities can become “smart” over time depending on the integration of technology into pre-existing city life.

I see a smart city as a city that is able to use technology to make itself more accessible to all residents. Portland is a very quaint city in that it fits within a specific New England architectural style, so a mass overhaul of Portland’s architecture to would not only be expensive, but would cause Portland to lose its New England tourism draw. Portland is capable of incorporating technology in other ways in order to benefit all of its citizens. As Margarita Angelidou says in her article “Smart city policies: A spatial approach,” “emphasis should be placed on regenerating degraded urban areas,” rather than just starting from scratch. This is entirely applicable to playspaces in Portland, as Portland’s already existing playgrounds can be redone and new ones can be created in derelict space in order to create technologically advanced, adaptable playgrounds.

Literature Review:

While the idea of a “weather-adaptable” playground is entirely new, the idea of play as a crucial part of a child’s development is supported by a number of national and international organizations. For example, the USA chapter of the International Play Association’s stated purpose is “to protect, preserve, and promote play as a fundamental right for all humans.” Roger Hart, the director of the Children’s Environments Research Group at CUNY, echoes this in an article in which he makes a claim about children’s right to play as a “basic right, fundamental to children’s development” based off of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child was a meeting in 1989 that wrote a document with a number of articles relating to the rights of all children. Article 31 of the document declares that “States Parties recognize the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.” Since then, many researchers have worked tirelessly to stress the importance of play in children’s lives and how to incorporate new ideas of play into playspaces.

A considerable portion of literature on the idea of play is primarily focused on the link between outdoor playtime and its medical benefits, such as a decrease in obesity. More recent research has focused on creating new kinds of playspaces as well. In an article for Parks & Recreation, associate editor Samantha Bartram discusses two important thoughts, the idea of “play deserts,” spaces where there is a lack of playspace, and how fewer than four out of ten Americans live within walking distance of a park. In another article for Parks & Recreation, Steve Casey discusses the redevelopment of a playground in Missouri into an adventure playground. This playground not only incorporates the idea of “free play” into its design, but also happens to be a very environmentally sustainable playground in its construction and function. These articles both highlight the need to create playspace where it lacks and the need to do so in creative and ecologically friendly ways. They reference the ways in which the development of adequate play space is difficult; in certain regions, it does not exist at all, and in others, economic, geographic, social, and visual factors have to be taken into account before the construction of a playground.

While researchers are away of the importance of play in a child’s development, very little research has done about the incorporation of smart technology into playspaces. In my research, I browsed numerous technology websites to look into how playgrounds are currently being designed. My search led me towards three websites in particular, wired.com, gizmodo.com, and nytimes.com. Through these websites, I found numerous contemporary playspace ideas. One article I read on wired.com outlines the creation of a company, Free Play, focused on “creating a series of abstract play structures that will challenge children’s creativity during playtime.” Free Play structures are designed in a way so that children can interact with them how they please, a very new idea compared to a playground containing a typical swing and ladder. Giving children the freedom to interface with playspaces in unique ways allows them a certain level of freedom that does not necessarily exist in a standard playground.

Figure 1: A playspace designed by Free Play, a company focused on bringing imagination-based play to children through unique playspace pieces.

Figure 1: A playspace designed by Free Play, a company focused on bringing imagination-based play to children through unique playspace pieces.

Another article on wired.com outlines a 2010 contest on the website for designing the future of playgrounds and contains images of newfangled playgrounds that could exist in the year 2024. These playgrounds are complete with an autonomous stroller rink, 360º rocket swing, and 10-G merry go round. While these ideas are not currently feasible in terms of safety, cost, and implementation, they speak to the creativity that can go into the construction of playgrounds today.

An article from the New York Times, “Beer for Me, Apple Juice for Her,” outlines a very unique idea of a playspace, the German beer garden, as a space in which parents and children can come together, both indoors and outdoors, to play. In one beer hall in Brooklyn, NY, there is even a “Babies & Bier” playgroup with a $10 entrance fee that includes snacks and drinks (both alcoholic and nonalcoholic). The owner of the Brooklyn beer hall started the playgroups “to address a lack of indoor play spaces” because she found that playspaces options were quite limited in inclement weather. While not exactly smart technology, this is a unique way to incorporate the element of play into less-traditional locations and to acknowledge that play can be encouraged and incorporated into other cultural traditions.

The final article I will discuss is a gizmodo.com article that describes a Danish plan to convert parking garages into multi-functional spaces. By adding open space primarily on top of parking garages, Copenhagen will be able to use otherwise useless space and turn it into parks, workout zones, and gardens for its residents. While this idea is not necessarily weather-proof or adaptable, it is one way in which cities can revamp pre-existing structures into new, more aesthetically pleasing, and functional spaces.

Figure 2: A sketch of what the Copenhagen parking garage playspaces could look like.

Figure 2: A sketch of what the Copenhagen parking garage playspaces could look like.

Methodology:

Over a period of two months, I spent time exploring Portland and observing my surroundings. While at a café in the Arts District, Local Sprouts Cooperative, I realized that there was a significant population of children in Portland that I had not previously noticed. I visited Local Sprouts Cooperative on a cloudy Saturday morning in late October and found the café to be almost entirely populated by parents and their young children. Local Sprouts Cooperative seems to be a very kid-friendly café and even provides space in a corner of the café as a children’s play area. Seeing such a high density of children in a café made me wonder why they were playing there and not outdoors in a playspace. If the weather were accommodating and they play space were close by, might parents have preferred to be there with their kids instead of packed into a café’s children’s corner?

The next portion of my research was spent making observations throughout a neighborhood while on a transect walk. I chose to walk through East Bayside and Munjoy Hill and focused specifically on looking for examples of educational infrastructure. For the purpose of my walk, I wanted to look at where schools and their playgrounds were located among the neighborhoods. Prior to my walk, I made note of where schools were listed on Google Maps so that as I walked by them, I see whether they had playgrounds. Many of the schools listed on my map did not actually exist; further, there were very few playgrounds spread out through the two neighborhoods. While my fieldwork has been limited in locations of Portland as a whole, the lack of playgrounds in the downtown area makes me think that Portland is underserving its youth by not providing them with their “right to play” and their “right to the city.”

Having finished my physical fieldwork in Portland, I turned to my computer for the next portion of my research. Using QGIS Software, I mapped out locations of schools and playgrounds in Portland (Figure 3) to look at where schools were located, where their specific playgrounds were located, and where neighborhood playgrounds were located with respect to schools. Looking at this map, however, I realized that it was not enough to simply map out the locations of schools and playgrounds. While many students are able to go to playgrounds straight from school, students, in my experience, are more likely to play near their homes. For this, I needed to create another map detailing where playgrounds are with respect to where the majority of students live.

Figure 3: Location of Portland schools and playspaces on mainland Portland. Data from City of Portland data sets, kaboom.org.

In order to do this, I mapped data from the US Census against the locations of schools and playgrounds (Figure 4). Using the percentages of residents under 18, I was able to compare where children live in Portland to where schools and playspaces are. The darkest blue portions of the map are the highest percentages of under-18 residents, between 21.8% and 24.4%. The white portions are the lowest percentages of under-18 residents, between 6.21% and 12.22%. On both maps, I chose to omit island portions of Portland, as full census data was not always available and schools and playgrounds were few and far between.

Figure 4: Location of Portland schools and playspaces and percentage of residents under the age of 18. Data from City of Portland data sets, kaboom.org, US Census.

The final element of my research was to look at how playgrounds are being designed and used elsewhere as inspiration for my policy recommendations for Portland. For this, I turned to the internet and looked at a variety of sources, including academic, media, and news sources. Many of these sources were on the development of new, more imagination-inspired playgrounds (such as those mentioned in the Literature Review section); others were on the idea of play as a necessary part of children’s development.

Findings:

When I looked at both of my maps, I found that Figure 3 makes it seem as though there are quite a number of playspaces around Portland near all schools. However, with the addition of the US Census data, it became obvious to me that while there seems to be a larger concentration of playspaces in the downtown area of Portland, there are very few playspaces in regions where children actually live. The darkest blue portions of the map in Figure 4 are not only the regions with the highest portion of under-18 residents, but are also the regions with the fewest playspaces.

My online research led me to numerous playspace ideas that have not been widely developed yet, but sadly did not lead me to any already existing, physically adaptable, weather-proof playspace ideas. While many people are working towards new ideas of playspaces and trying to stay away from a classic model of swing set, ladder, and monkey bars, no one has gone past the imagination playground to create a playground model that is functional in different weather conditions.

Discussion:

My research has led me to the conclusion that Portland not only needs more playgrounds, but also needs weather-adaptable playgrounds so that children might have the ability to play outside throughout all four seasons. I also concluded that Portland is currently failing to provide access to parks or play space as proposed in its Comprehensive Plan. If it is recommended that people have some kind of park or play space within walking distance, or ½ mile, from their home, it is impossible that Portland’s youth have adequate access and ability to get to a park or playground. Portland is not living up to its own policy if it does not add playspaces in the areas of highest under-18 population density.

I propose that Portland expand the number of playspaces predominantly in two areas, in zones where there are too few playspaces and a high density of the under-18 population, and in poverty zones. By placing new playspaces in these areas, they will hopefully be able to accomplish two goals. First, they will support the city’s goals to provide playspaces, and second, they may contribute to the revitalization of impoverished communities. I also believe that creating playspaces on top of already existing buildings such as parking lots (similar to the idea being implemented in Copenhagen) is a viable way to create playspace infrastructure in areas where there might not be already existing city-owned free space. Portland is not a city full of skyscrapers, so rooftop gardens and playgrounds in the downtown area would also allow many people a beautiful view of the waterfront.

Most interestingly in my mind, I propose that new and pre-existing playspaces be designed or redesigned in such a way that they are physically adaptable depending on weather conditions. Maine is known for its snowy conditions, and in the case of inclement weather, of which there is a significant amount during the winter, children are stuck inside to play. Playgrounds can be designed with automated moving parts, sensors, and computer connections to change their function based on current weather or weather forecasts. For example, a playground could have a portion that in rainy weather has a covered portion to keep segments of the playground dry and usable in the rain. Other structures can be built on inclines and designed in such a way that integrate scientific exploration in the summer vis-à-vis running water, which helps kids learn about creating and changing currents. Similarly, these structures could have a retractable cover that can then convert into speed controlled, toboggan-like apparatus creating safe snow play and allowing children to sled in more regions of Portland. Playground function would only adapt based on the current outdoor weather or the weather forecast, but seeing as Portland often has rainy or snowy weather, the playgrounds would never be too static in their function. To add to the idea of playspaces in paring garage space, playspace can be designed and built into the second to last level of a garage, providing views and air, but protection from snow and rain. Lastly, technology could also be used to identify materials that are ecologically safe and made of a material that is not slippery to gloves and mittens. So many young people, geared up in winter wear, would love to play outdoors, but cannot grip or safely maneuver play areas.

Technology can enhance a playground’s adaptability. By connecting directly to a weather forecast or Portland’s main weather system, playgrounds could be programmed to move parts prior to a change in weather. All this would take is a simple computer connection to a main database and, either automatically or at the push of a button from someone in Portland’s Recreation and Facilities Management Department, a playground would adapt its moving parts to best fit the weather circumstances. Playgrounds could also be outfitted with sensors near the entrances to gauge how many people are using them and at what times of the day and year they are most frequently using them; this data could be used for future analysis of locational placement of new playgrounds as well as reevaluation of existing playgrounds and their popularity.

New and renovated playgrounds placed in more locations around the city would impact a larger number of residents in Portland. By giving more people walking distance access to a playspace and the ability to use the playspace in all kinds of weather, more of the city’s population would be served for the better. The audience for playspaces would be primarily youth, but not only those of a high socioeconomic class. Statistically speaking, low-income students spend more time in front of a TV screen than their high-income peers and therefore are more likely to struggle with issues of obesity. Outdoor playspaces can act as a means by which to keep youth off the streets, but also limit their indoor screen time and keep them healthier.

Portland’s Comprehensive Plan, with detailed goals for recreational access for its residents, was drafted in 2002 with guidelines for a recreational plan published since 1995.

Now, almost 20 years later, it seems to me that Portland has still not met these goals for recreational space around the city. Not only does Portland’s official policy on the matter state that Portland will “develop a comprehensive management plan for the City’s park system… to meet the needs of Portland’s citizens” but it also states that Portland will “acquire and improve additional facilities in neighborhoods, which have been determined to have inadequate or insufficient open spaces and recreational resources.” I believe that Portland needs to amend its policy documents so that it can work towards giving more people the access to parks and playgrounds within walking distance of their homes and take measures to provide adequate recreational opportunities throughout all four seasons.

Conclusion:

The City of Portland is a thriving, cultural hub in northern New England. However, its play infrastructure is distributed inequitably and inadequately to its various neighborhoods. In order to provide its citizens with proper park and playspace infrastructure, Portland should amend its policy documents in order to provide more and improved playspaces throughout the city. Existing playspaces should be revamped and new ones should be created in order to give all of Portland’s youth adequate access to play. These playspaces should be designed to be technologically sound and versatile; if they are able to change their function throughout all four seasons of the year, then more youth will have access to them at all times, regardless of weather. As Carmen Harris, epidemiologist at the CDC, says, “As great as technology and engineering are, we have perhaps engineered ourselves out of physical activity.” Using technology to improve the quality of play and availability to it across all four seasons and to increase access to playspace for all of its citizens, independent of neighborhood, Portland can engineer itself back into giving more people the possibility of physical activity and show other cities the kind of technology pioneer that Portland can be.

Bus data collection

Emma Chow Final Paper: Recommendations for Creating a Recreation Hub in India Street Neighborhood

Emma Chow

Professor Gieseking

The Digital Image of the City

12/17/14

Recommendations for Creating a Recreation Hub at the Foot of India Street, Portland, Maine

Research Question

Once a bustling commercial hub of industry, Portland’s historic India Street Neighborhood has lost its neighborhood vitality and is now in need of revitalization. The India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan, published September 2014, is comprised of five goals, six vision statements, thirteen development principles, and twelve critical actions.[1] This paper focuses on Critical Action 11 – Create a Recreation Hub at the Foot of India Street, by giving recommendations for developing the Recreation Hub to best align with the plan’s vision. The recommendations aim to meet the following goals and visions: Goal 5: Enhanced Mixed-Use Nature of Neighborhood; Vision Statement 5: A Healthy, Connected, and Active Neighborhood; Vision Statement 6: A Neighborhood of Strong Identity.

Integrating a workout park, green space, solar lighting, public art, seating, and small local businesses will create an enjoyable destination space for people of all ages. India Street Neighborhood (ISN) has great potential to leverage the vacant space at the foot of India St. to create a recreation hub that will effectively energize both the ISN neighborhood and the entire City of Portland.

Approach to the Common Good for the City

A city can serve the common good by developing its public spaces in a manner that allows Setha Low’s five freedoms[2] — freedom of access, freedom of action, freedom to claim, freedom to change, and freedom to ownership – to be realized. Cities must take measures to ensure public space maintains civilian safety; is accessible by all groups regardless of race, gender, age, or socioeconomic status; only allots temporary private ownership (i.e. evening or weekend events); and relinquishes power to the people for further shaping the space. Portland may be tempted to supplement limited government funding for public space with private dollars; however, the City should be wary of fostering any public-private partnerships that will turn its parks and squares into permanent large-scale advertisements. This may be especially likely given Maine’s regulations against billboards. Ultimately, government decisions should always be made to maximize the common good of the public, rather than the private.

Approach to the Smart City

A Smart City is one that first realizes the way technology can expand people’s potential well-being, and then implements technological systems with the goal of actually reaching this potential. The Smart City creates policies that incorporate and leverage available technologies to further the city towards where it wants to go[3]. Technology does not dominate the Smart City, but simply enhances the quality of the essential features of a city: infrastructure, housing, and public space. The Smart City uses technology to address issues such as poverty, urban food deserts, climate change, reliable energy supply, global communication, and transportation[4]. The most successful Smart Cities carefully adopt technology to help alleviate their greatest issues while still keeping people at the forefront of their decision-making.

The Smart City not only uses technology to install smart meters, coordinate traffic lights according to congestion patterns, and display subway wait times in real time, but also uses technology to enhance public space. For instance, cities can install free Wi-Fi in public space to improve Internet access and provide outdoor workspace, where tasks can be completed while surrounded by nature. Technology can be integrated into public space and shape the way people use that space. Technology can also be used to create a virtual communication platform for engaging the future users of public space in the planning process. Residents are the everyday consumers of the city, therefore, their voices should be heard – online forums and email surveys may be a great way to ensure the most voices are heard. Finally, the Smart City makes its data available to the public so people can develop apps to meet their changing needs. Apps can be designed to maximize people’s usage of public space, making them aware of where these spaces are located and what they can do there.

Literature Review

Academic Literature:

Green areas in cities are essential for sustainable urban development. Here, the word sustainable is used to describe cities that simultaneously ensure sustainable environmental, social, and human health. Additionally, green infrastructure both directly and indirectly, generates a series of economic benefits that will be realized in the future.[5] Accessible public space in cities improves the quality of life for residents by “facilitating social contact between people of all ages, both informally and through participation in social and cultural events (local festivals, civic celebrations or doing some theater work, film, etc.)”[6] Recent research has expanded experts’ understanding of well-being, revealing humans are social animals that experience an increase in well-being from pro-social behavior.[7] Well-designed public space provides a permanent site for consistent social interactions, thus further developing social capital and building community.

Public space can be designed to host an array of recreation opportunities, such as workout parks, walking and biking paths, children’s play areas, soccer fields, and open space for yoga classes. Green public space and recreation space can bolster the identity of a neighborhood, consequently creating a higher quality community environment for residents and attracting tourists and private investment, as well. When green spaces are installed, property values tend to increase: “Numerous studies have shown that housing and land value, which are adjacent to green spaces, may increase by 8% to 20%.”[8] Therefore, issues of gentrification need to be carefully considered when implementing projects for creating green space in cities. Other economic benefits include: savings healthier residents experience due to improved physical health, the revenues earned by vendors at cultural events, reduced storm water management costs, and increased spending by tourists.[9]

Waterfront cities have an incredible opportunity to leverage the natural water amenity as a means for improving residents’ quality of life. By facilitating physical and emotional contact with water, public waterfront space can foster strong relationships between urban populations and water. As a result, residents’ well-being is heightened by the enjoyment they derive from waterfront activities. Residents also gain an appreciation for the water and are subsequently compelled to protect the essential resource by changing their behavior and/or supporting water conservation groups.[10]

The success of public space is largely determined by its ability to meet people’s needs; the only way for planners to know those needs is by including the public in the planning process. Traditional image-based survey methods involve showing often biased, manipulated photos to participants; therefore allowing planners to elicit intended opinions from the public. Being able to say they involved public participation in their planning is often more important to planners than actually generating meaningful input. In Participant Driven Planning (PDPE), participants provide photos and are able to engage in meaningful dialogue about what they like/do not like about the places they present. Bottom-up planning processes, as opposed to expert-driven top-down approaches, ensure public space is designed to meet the real needs of the community.[11] Additionally, as MIT’s Places in the Making whitepaper concludes, the placemaking process is just as important for empowering local communities as the physical outcome is.[12]

Media Literature:

There is a national movement to “push back on the hegemony of the automobile and make public spaces accessible to pedestrians.”[13] Cities are increasingly realizing that designing for cars attracts more cars, while designing for people attracts more people. Great public space pulls people outdoors and then gives them a reason to stay – whether it be something to do, places to socialize, or beautiful scenery to look at. Many formerly industrial cities were built along the water for easy access to transportation channels, and now those cities are transforming their waterfronts to be multi-use areas for people.

Open space can be transformed using technology and nature to create dynamic public space that attracts tourists and residents alike. Three key features that need to be kept in mind when creating public space that will develop community attachment, are: social offerings, openness, and beauty.[14] Important features in any public space include: seating, lighting, and grass, plants, and trees. Many American cities are taking steps to create public space that offers recreation opportunities. New York City installed its first adult playground (an outdoor workout park) at Macombs Dam Park in the Bronx in 2010, and plans to install as many as two-dozen similar parks by the end of 2014.[15] Miami-Dade County, Los Angeles, and Boston have all installed public adult fitness facilities, as well.[16] The size and cost of workout parks can range from the $40,000 (the average cost per site in Los Angeles) to more than $200,000 (the cost of New York City’s largest park).[17] New technologies are even making it possible to install workout parks that generate electrical energy from users’ exercise on the fitness equipment; however, these technologies are not yet widespread since they are more expensive than conventional workout parks.[18] Workout parks are not the only solution for creating recreation space for adults. Boston’s Lawn Street D, for instance, offers circular LED-lit swings that change color according to movement, bocce ball, beanbag toss, Adirondack chairs, and a sound stage for music.[19]

Lighting can be used to transform public space at night. One team at the 2012 Makeathon in San Francisco designed an affordable technology for adding digital light projections to buildings and brighten up dark alleyways.[20] Another team at the same tech event offered technology to create a portable light up stage for performances in public space.

Methods

The Portland Master Plan and India Street Neighborhood Master Plan documents were first reviewed to understand the goals for the city and this specific neighborhood. Next, the History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood[21] was reviewed to gain familiarity about the history of the neighborhood and the important role the waterfront has, and continues to play, in developing Portland’s economic and physical landscape. An academic literature review was completed to provide insights into the economic, health, and environmental benefits of public space along the waterfront, as well as the importance of authentic public participation during the planning process. Media sources provided exposure into emerging technologies used for workout parks and lighting features in public space, as well as the value of placemaking for fostering community.

Conclusions about public space and opportunities to enjoy the waterfront were drawn from a series of data sets, including: consolidated data on the 97 mental maps collected by Digital Image of the City students and recommendations proposed by those 97 participants, as well as QGIS shape files provided by the City of Portland.

Maps were created to visualize the proposed area of development and guide planning recommendations. A map was first created to identify ISN and the future site of the Recreation Hub. Another map with a broader perspective reveals the extent and location of existing outdoor recreation space in the city, while contextualizing the Recreation Hub with respect to neighboring residential areas. The City of Portland provided data identifying the types of open space in Portland – areas identified as a trail, park, golf course, or playground were all grouped to map “recreation space”. Another map was created using data to illustrate the connection between different recreation spaces in the ISN area and the need for accessibility to the Recreation Hub. Bus route schedules were examined to understand the scope of accessibility.

Historical maps provided by the City of Portland were also referenced. These maps provided insights into how the city’s growth was fueled by the waterfront activity at the foot of India St and the commercial center of India St., Exchange St., and Middle St. Historic sources discuss the interplay between daily life in Portland and the waterfront; highlighting how it has changed from the eighteenth century to present day.

Findings

Historic maps and sources indicate that ISN’s identity as the city’s commercial center has changed over the years. Now, the neighborhood serves as a transitional area between the rapidly gentrifying neighborhood of Munjoy Hill and the tourist and commercial center of the Old Port and Commercial St. ISN lacks a sense of clear identity.

Fig 1. (Left) Portland in 1775 with India St. (King St. then) as a major artery to the waterfront. (Right) Portland in 1866 featuring the rail network along the waterfront centered at India St.[22]

As Fig 3. Illustrates, recreation space is concentrated around the Eastern and Northern edges of the city with very little in the center or along the waterfront. Piers and tightly concentrated streets dominate the waterfront. ISN is situated on the Eastern part of the city near the waterfront.

Fig 3. Recreation space (trails, parks, playgrounds, golf courses) in Portland.

Fig 4. ISN and its major streets are highlighted, along with the site for the Recreation Hub.

ISN is dominated by open space that is not used for recreation and large buildings that consist of industrial buildings, parking garages, and hotels. There is no recreation space in ISN, there are only three recreation sites located just beyond the neighborhood boundaries. Residential neighborhoods border ISN, as indicated by the many small buildings to the Northeast and Northwest.

Fig 5. Bus routes, sidewalks, and streets connecting ISN to the rest of the city.

Bus route 8, which stops at Commercial St. and India St. provides access to the Recreation Hub. However, the bus only runs every 30 – 45 minutes on weekdays and 40 – 50 minutes on Saturdays, with no service on Sundays. Major streets in the area have sidewalks, but some are disconnected in and immediately around ISN.

Discussion

My recommendations have dual aims: (1) to offer feasible solutions for transforming the open space at the foot of India St. into a Recreation Hub, and (2) to suggest the optimal planning process for engaging public participation. I recommend installing an adult workout park, a play area for children, comfortable seating, lighting, and a storm-water collection pond. My recommendation for the planning process leverages technology and the web interface to provide a highly-accessibly and interactive platform for residents to voice their opinions.

The Recreation Hub needs to be developed with the goal of maximum usership in mind. The area can establish itself as a destination that draws people to ISN and gives them a reason to stay. Currently, popular restaurants, such as Hugo’s, Duckfat, and Eventide Oyster Company located on Middle St., are the main attraction to the neighborhood. The success of these restaurants, as well as nearby shops and the popular Italian landmark, Micucci Grocery Store, has already initiated a revitalization process; however, public space is still lacking. Even more, Portland as a whole presents limited opportunities for its residents to enjoy the waterfront. The water is a valuable natural amenity whose ability to improve quality of life should be better taken advantage of. Not only can transforming the open space at the foot of India St. into a Recreation Hub provide opportunities for people to spend time near the water, but it will also provide much needed opportunities for recreation.

While Portland does have some recreation sites, they are primarily located along the North and Northeastern edges of the city. The new Recreation Hub should include a workout park for adults, consisting of stationary equipment and signage providing exercise information. The workout park should occupy no more than a quarter of the total space. A play area for children should occupy another quarter of the space. Depending on budget limitations and residents’ desires, the play area can be as simple as a paved section for chalk or a sandbox, or full on playground equipment. The children’s area should be surrounded by benches for parents to sit on while attending to their children. At least half of the space should be made of natural materials. This includes open grass patches for picnics, bushes to separate the Recreation Hub from the street, flowers, and trees to provide shade. If space permits, a pond that collects storm water and then uses it to irrigate the greenery should be installed. The pond would minimize run-off and save water, as well as create a feature that children can interact with. Seating should be positioned around the pond so people of all ages can sit and relax, enjoying the calming effects of the water.

Lighting is essential, especially given the dark days of Maine during the late fall and winter. The City of Portland should partner with students at MECA, University of Maine, Bowdoin College, and Bates College and challenge them to create public art installations in the form of solar-powered lights. Different lights can be installed each season, transforming the look and feel of the space and showcasing many different student-artists. These installations would be an ideal way to incorporate public art into the space while minimizing commissioning and electricity costs and ensuring visitors’ safety.

It is critical that the Recreation Hub is made accessible to the rest of the city, especially as the most densely populated residential areas are located beyond the boundaries of ISN. While Bus 8 stops right by the Recreation Hub site, the bus does not run frequently and does not run on Sundays. Since the Recreation Hub will be catering to all ages, family visitation rates are expected to be highest on weekends when parents have the most time to spend time with their children. It would be advisable to increase the frequency of Bus 8, and at the very least, provide service on Sundays. The surrounding sidewalk network appears to be sufficient, however, the Recreation Hub needs to meet cyclists’ needs by offering ample bike racks. The Recreation Hub should also be well connected to the preexisting recreation area of the Eastern Promenade. This lookout area attracts many visitors and the Recreation Hub could become a final destination for these people, especially runners and cyclists seeking an additional workout. Establishing this connection and then educating the public about it will be key to increasing usership.

Finally, the Recreation Hub should be multi-purpose, capable of serving as an event venue year-round. Events can integrate local private businesses, to take part in food festivals. Similar the Art Walk model, one evening each month, the Recreation Hub could invite a selection of Portland restaurants to sell a few menu items at a capped cost. Temporary seating could be set up so people could pick up food from restaurant booths and then sit and eat. Musicians could be invited to provide entertainment. The food offering could be tailored to the season – outdoor heaters and blankets, Duckfat poutine, a hot chocolate stand, and snow sculpting competitions in the winter; Nosh burgers, a lemonade stand, and popsicles in the summer. This would be a good way for ISN to engage local businesses in community-building events without giving them long-term ownership to the space.

Conclusion

The recommendations detailed in this paper provide a means for Portland to significantly revitalize ISN. GIS analysis indicates that Portland needs to expand its green space and provide increased opportunities for residents to enjoy the waterfront as a part of their daily lifestyles. If the Recreation Hub incorporates the recommended features – an adult workout park, children’s play area, seating, green space, public art solar lighting, and an irrigation pond – the space will become a prominent destination spot for both residents and tourists. What these features finally look like should be determined by public preferences. Portland can best listen to the public by establishing an online platform that anyone can easily access to voice their opinions. The platform would become a forum where people can vote on options (i.e. four options for a children’s play area), comment on proposed solutions, and even post photos of places in Portland or elsewhere explaining what they like or do not like about it. Essentially, an online “public space” should be created to develop the public space to ensure people’s needs are best met.

The design of the Recreation Hub is critical, but accessibility ultimately determines its public usage. Thus, Portland should increase its Route 8 service to the Recreation Hub, ensure sidewalks are well maintained, and create a well-marked connection to the Eastern Promenade. Public awareness about the space can be increased through newspaper articles, newscast features, and events sponsored by local businesses. The Recreation Hub can become an engaging dynamic place for people of all ages to enjoy the waterfront, play, socialize, relax, and engage with nature. In these ways, the Recreation Hub has great potential to improve people’s quality of life and well-being. The recommendations discussed in this paper ensure the Recreation Hub will ultimately Portland help further ISN towards the goals and visions outlined in the India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan.

Works Cited

Beatley, Timothy. Biophilic Cities. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. 2010.

Cicea, Claudiu and Corina Pîrlogea. “Green Spaces and Public Health in Urban Areas.” _____Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 6, no. 1 (02, 2011): 83-92. _____http://ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/858207241?acc_____ountid=9681.

City of Portland. India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan. September 2014. _____http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/6471.

Durgahee, Ayesha and Matthew Knight. “New Gym Turns Workout into Watts.” CNN. _____November, 27, 2011. http://www.cnn.com/2012/11/27/world/europe/gym-workout-watts-_____electricity/.

Hu, Winnie. “Mom, Dad, This Playground’s for You.” New York Times, June 29, 2012. _____http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/01/nyregion/new-york-introduces-its-first-adult-_____playground.html?pagewanted=all&module=Search&mabReward=relbias%3As%2C%7B_____%222%22%3A%22RI%3A14%22%7D&_r=2&.

Hurst, Nathan. “Digitally Enhancing Public Spaces at the Urban Prototyping Makeathon.” _____Wired. November 6, 2012. http://www.wired.com/2012/10/up-makeathon/.

Larry, Julie and Gabrielle Daniello. History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood. Accessed _____November 17, 2014. http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/4276.

Low, Setha M. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial _____Plaza.” in After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, ed. Michael Sorkin _____and Sharon Zukin (New York: Routledge).163-172.

Perry, Tony. “San Diego’s Waterfront Makeover is Heavy on Public Space.” Los Angeles Times. _____December 8, 2014. http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-san-diego-waterfront-_____20141209-story.html#page=1.

Petty, Raven. “Four Cities with Playgrounds for Adults.” Livability. November 17, 2014. _____http://livability.com/health-and-wellness/four-cities-playgrounds-adults.

Rutherford, Linda. “Why Public Places are Key for Transforming Our Communities.” Greenbiz, _____April 25, 2014. http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2014/04/25/why-public-places-are-key-_____transforming-our-communities.

Sareen, Himanshu. “Smart Cities: A Brave New Digital World.” Wired, March 28, 2013. _____http://www.wired.com/2013/03/smart-cities-a-brave-new-digital-world/.

Schulkin, Jay. Adaptation and Well-being: Social Allostasis. Cambridge: Cambridge University _____Press, 2011.

Silberberg, Susan. Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities. _____Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013). _____http://dusp.mit.edu/cdd/project/placemaking.

Tomer, Adie and Rob Puentes. “Here’s the Right Way to Build the Futuristic Cities of Our _____Dreams.” Wired. April 23, 2014. http://www.wired.com/2014/04/heres-the-right-way-to-_____build-the-futuristic-cities-of-our-dreams/.

Van Auken, Paul, Shaun Golding, and James Brown. “Prompting with Pictures: Determinism _____and Democracy in Planning.” American Planning Association: Making Great _____Communities Happen. 2012.

[1] City of Portland, India Street Sustainable Neighborhood Plan, September 2014, http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/6471.

[2] Setha M. Low, “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza,” in After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, ed. Michael Sorkin and Sharon Zukin (New York: Routledge), 163-172.

[3] Adie Tomer and Rob Puentes, “Here’s the Right Way to Build the Futuristic Cities of Our Dreams,” Wired, April 23, 2014. http://www.wired.com/2014/04/heres-the-right-way-to-build-the-futuristic-cities-of-our-dreams/.

[4] Himanshu Sareen, “Smart Cities: A Brave New Digital World,” Wired, March 28, 2013, http://www.wired.com/2013/03/smart-cities-a-brave-new-digital-world/.

[5] Claudiu Cicea and Corina Pîrlogea, “Green Spaces and Public Health in Urban Areas,” Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 6, no. 1 (02, 2011): 83-92, http://ezproxy.bowdoin.edu/login?url=http://search.proquest.com/docview/858207241?accountid=9681.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jay Schulkin, Adaptation and Well-being: Social Allostasis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 3.

[8] Claudiu Cicea and Corina Pîrlogea, “Green Spaces and Public Health in Urban Areas.”

[9] Ibid.

[10] Timothy Beatley, Biophilic Cities (Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2010), 6.

[11] Paul Van Auken, Shaun Golding, and James Brown, “Promting with Pictures: Determinism and Democracy in Planning,” American Planning Association: Making Great Communities Happen (2012), 2.

[12] Susan Silberberg, Places in the Making: How Placemaking Builds Places and Communities,” Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2013), http://dusp.mit.edu/cdd/project/placemaking.

[13] Tony Perry, “San Diego’s Waterfront Makeover is Heavy on Public Space,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 2014, http://www.latimes.com/local/california/la-me-san-diego-waterfront-20141209-story.html#page=1.

[14] Linda Rutherford, “Why Public Places are Key for Transforming Our Communities,” Greenbiz, April 25, 2014, http://www.greenbiz.com/blog/2014/04/25/why-public-places-are-key-transforming-our-communities.

[15] Winnie Hu, “Mom, Dad, This Playground’s for You,” New York Times, June 29, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/07/01/nyregion/new-york-introduces-its-first-adult-playground.html?pagewanted=all&module=Search&mabReward=relbias%3As%2C%7B%222%22%3A%22RI%3A14%22%7D&_r=2&.

[16] Raven Petty, “Four Cities with Playgrounds for Adults,” Livability, November 17, 2014, http://livability.com/health-and-wellness/four-cities-playgrounds-adults.

[17] Tony Perry, “San Diego’s Waterfront Makeover is Heavy on Public Space”.

[18] Ayesha Durgahee and Matthew Knight, “New Gym Turns Workout into Watts,” CNN, November, 27, 2011, http://www.cnn.com/2012/11/27/world/europe/gym-workout-watts-electricity/.

[19] Linda Rutherford, “Why Public Places are Key for Transforming Our Communities”.

[20] Nathan Hurst, “Digitally Enhancing Public Spaces at the Urban Prototyping Makeathon,” Wired, November, 6, 2012, http://www.wired.com/2012/10/up-makeathon/.

[21] Julie Larry and Gabrielle Daniello, History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood, accessed November 17, 2014, http://www.portlandmaine.gov/DocumentCenter/Home/View/4276.

[22] Julie Larry and Gabrielle Daniello, History of Portland’s India Street Neighborhood

Resource Map Application

According to the 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, national homelessness has declined by over 9% since 2007. [1] This is not the case in Portland, Maine, where the homeless population grew by 70.3% from 2009 to 2013. [2] A man I interviewed outside Preble Street Resource Center commented that other cities are sending their homeless to Portland for its strong outreach programs. Despite the renown of these programs – the Preble Street ‘housing first’ model, in particular – these facilities are overwhelmed. In particularly busy months, only 272 sleeping spots were available for nearly double the people [2].

A Resource Map application would draw on Portland’s own residents, organizations, and businesses to augment the work of the resource centers in helping this population to its feet. The map would include all of the city’s shelters, pantries, resource centers, and libraries, but its primary focus would be interaction between Portlanders in need and those who are able and willing to help. Users would create their own posts on the map, both offering and seeking out assistance. An individual could create a listing at the public library offering help with crafting a resume, English tutoring, or teaching basic computer skills. An individual could post an odd job like shoveling a driveway. People could post on the map listing items they are giving away. Businesses could place themselves on the map, perhaps offering up free wifi, free food, or other resources.

Accessibility is a key concern with any tech-related urban project – as noted by Setha Low, this app cannot function if it “limits participation to those who can afford it.” [3] A large percentage of the targeted population will not have dependable access to smartphones or the Internet, so it is essential to ensure their ability to use the app. Portland’s homeless do have computer access at Preble Street and the Portland Public Library, and are likely to have basic cell phones. Thus, the app would include an SMS texting function. A user would text in a request – asking for a ride to a job interview, for example – and other users could respond to that person with a time and a place to meet up. Users of the app could also subscribe to a daily text containing an updated list of available services, as well as a list of that day’s requests for assistance.

This project relies heavily on the generosity of the people of Portland, thus creating a sense of communal care and organization around the problem of homelessness. This rising issue in the city has coincided with an influx of tourism and gentrification. Involving a varied group of Portland businesses and citizens in this issue – ranging from stores like Salvation Army to stores like Portland Architectural Salvage – might help to ground them in the often grim realities of the city. Additionally, the app would give the city’s skyrocketing new establishments – condos-with-a-view, trendy coffee shops, and pricey antique stores – the opportunity to make a positive change for the at-risk population of the city. In any urban center, as Don Mitchell wisely points out, “different people with different projects must necessarily struggle with one another.” [4] Ideally, the Resource Map application would allow for more engaging, productive, and enlightening “encounter and exchange” between the haves and have-nots of Portland. [4]

[1] “The 2013 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress.” HUD Exchange. 2013.

[2] Billings, Randy. “Homelessness Hits Record High in Portland.” Portland Press Herald. http://www.pressherald.com/2013/10/27/homelessness_hits_record_high_in_portland_/

[3] Low, Setha M. 2002. “Spaces of Reflection, Recovery, and Resistance: Reimagining the Postindustrial Plaza.” In After the World Trade Center: Rethinking New York City, edited by Micheal Sorkin and Sharon Zukin, 163-72. New York: Routledge, 2014

[4] Mitchell, Don. 2014 [2003]. “To Go Again to Hyde Park: Public Space, Rights and Social Justice.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al. New York: Routledge, 2014)

Portland’s Lifestyle Juxtapositions

In my walk through Portland, I was most struck by stark juxtapositions within the city in regards to standards of living. I noticed the construction of condos and apartments near blocks and blocks of identical low-income housing. I noticed the existence of a Planet Dog – a store exclusively for the accessories, beds, toys, and food receptacles of Portland’s canines – next to homeless people begging with signs on the street. I noticed the irony of an upscale antique store and a home entertainment store just down the road from the Preble Street Resource Center and Salvation Army.