WalkPortland: Enhancing the Pedestrian Experience in Portland, ME

Research question

Portland, Maine has a parking problem in its Downtown area. Residents, commuters, and tourists cite the parking situation as a detriment to the overall experience of the city. The city government is aware of the issue and has been working to modify the physical and legal structure regarding downtown parking to increase efficiency and enhance people’s experience of Portland. In my own research, I noticed a general sense of dissatisfaction with the physical capacity of downtown parking, but also a seemingly unnecessary reliance on cars for city as small in population and area as Portland.

The solution I propose is an extension of the city’s stated commitment in the 1991 Comprehensive Plan to “understand and enhance the physical framework of the built environment to assure a livable, pedestrian-oriented, human-scaled downtown.”[1] It would take the form of a mapping app, which would make parking information readily available and also serve as a legible, pedestrian-oriented map of Portland. A key feature of the app would be 5- and 10-minute walk radius maps that would hopefully help to reconnect Portlander’s perception of the city’s size and walkability to its actual area. The app would be supplemented by physical maps in downtown Portland, which increase the accessibility of this resource and also serve as advertisement for the app.

Approach to the common good for the city

The common good in the city rests in large part in the interactions between city government and the people it serves. A government that seeks to understand and respect the will of its people is one that seeks to act for the common good. This definition is cultural; it has to do with the comfortable maintenance and development of existing culture in the city. Portland’s existing policy regarding its Downtown states the city’s desire to develop the space in the best interests of the people, while being careful to maintain the existing culture and identity.[2]

Including systematic goals in writing towards respecting the people who occupy and create Downtown helps to keep “the common good” something that citizens help to define. City changes that do not align with the popular idea of common good are held accountable by town documents and goals such as that to “preserve and strengthen the unique identity and character of the Downtown.”[3]

It is also important, however, to question the existing structures and create plans and policy that keep in mind those for whom Downtown’s existing structure is not ideal, and who might prefer to see Downtown’s “unique identity” move in a different direction.

Approach to the smart city

In the age of growing populations and shrinking resources, the Smart city is efficient, safe, sustainable, and adaptable. The use of new technology is not explicit in this definition, but often the ideas or solutions that meet this description make use of new technologies. In terms of adaptability, too, the capacity of an existing structure to expand spontaneously or over time as needed speaks to its continuing usefulness and relevance; often this means that the structure is technologically updated.

In Against the Smart City, Adam Greenfield raises the important concern regarding the “seamlessness” with which technology is integrated into smart cities. He criticizes devices that are “bolt-ons rather than anything designed into the urban fabric itself ab initio.”[4] Portland’s commitment to maintaining the existing structure and identity of the Downtown presents somewhat of a challenge in utilizing new technologies in that space, but it also provides a foundation from which to build—one that ensures that the whatever solutions are put in place operate as a part of the city, rather than as an addition to it.

Greenfield also criticizes solutions in which “the collection and analysis of data [is] enshrined at the heart of someone’s conception of municipal stewardship.”[5] This hearkens back to the idea of the common good, bringing important concerns of privacy and security into the mix as the daily act of citizenship becomes a source of data-production. Because of its small size but strong sense of urbanity and community, Portland could be an excellent model of smart city technology employed with the common good very much in mind.

Besides maintaining thought of the common good, another important factor in helping smart cities to retain their “city-ness” is the concern of technological ubiquity. A city cannot be built only on smartphones, touchscreens, and Wi-Fi; it functions through human interactions. Tony Hiss[6], Guy Debord[7], and Henry Grabar[8] all speak to the place-driven, human quality of cities, especially through Hiss’s idea of “simultaneous perception” as one of the core qualities that makes a city a city. Almost as a modern day defense of Debord’s derive as a way of experiencing that quality of the city, Grabar points out, “The reverie of wandering, on foot or on wheels, can’t be calculated by an algorithm or prescribed by an app.”[9] However, technology can be used to enhance and facilitate human interactions and understandings of place, rather than make that understanding “unnecessary.” Hiss, Debord, and Grabar’s ideas are of great importance in the unique experience of being in a city, and it is possible to make them present in a smart city, as well. In terms of the WalkPortland app, keeping the app’s focus on getting people out of the shielded bubbles of their cars and out into the city is a way of using technology to promote and facilitate human interaction in the city.

Literature review

Andres Duany and Jeff Speck view “smart” not only as the utilization of new technology and design, but also as the return to some older forms of the same. Their book The Smart Growth Manual highlights “walkability” as a key feature of a smart city’s successful future. Unlike their parents’ generation, millennials (people born between approximately 1983 and 2000)[10] have tended not to buy their own cars, opting instead for a more walkable city life. And the “if you build it, they will come,” policy applies here: 64% of people first identify and move to a city they like, and then seek a job there.[11] Key to creating that desirable city image is “walkability.” Duany and Speck encourage planners to

“foster ‘walkable,’ close-knit neighborhoods: These places offer not just the opportunity to walk—sidewalks are a necessity—but something to walk to, whether it’s the corner store, the transit stop, or a school. A compact, walkable neighborhood contributes to peoples’ sense of community because neighbors get to know each other, not just each other’s cars”[12]

This community is the place for a city’s life, culture, and social capital to be created, learned, and reproduced.

In keeping with Greenfield’s concept of urban and technological seamlessness, Duany and Speck also advocate for “[taking] advantage of existing community assets: from local parks to neighborhood schools to transit systems, public investments should focus on getting the most out of what we’ve already built.”[13] One method they cite for encouraging people to leave their cars and walk is to make that the most economical option by imposing higher parking fees. This method incentivizes people to use public transportation or walk.

However, this solution raises its own set of concerns about who then gets to benefit from walkability. As Sarah Marusek discusses at length in Parking Politics, higher municipal fees such as parking costs have disproportionate effects between socioeconomic classes, and in this way parking becomes yet another way of separating those who have the right to the city and those who have the means to the city.[14] Curbside parking, an equalizer in the world of private and pay-to-stay parking lots, can be restrictive in ways that make driving possible for some and impossible for others. Marusek also cites a case study in which parking rights are connected to whether or not people can call themselves “residents.” At Amherst College, “from September through May, city streets are strictly reserved for town residents who have a town-sanctioned parking permit. This restriction is in place to keep visitors, i.e. students, from claiming parking spaces and leaving no place for ‘rightful’ residents to park during the school year.”[15] While the students reside there most of the year, they are not eligible to be considered residents of the town.

The takeaway from both Duany and Speck’s work and Marusek’s work is that urban planning innovations— smart or otherwise— have fallout of many different forms, affecting different groups of people in predictable and unpredictable ways. They key role of government in these situations is to respond not only to problems in the city but to their solutions as well.

The purpose behind the WalkPortland app is twofold: to decrease car use and car presence in Downtown Portland, and to help people to enjoy the city on foot. The decrease in car traffic may already be underway. A November 2014 article from the Portland Press Herald reported that in Maine, the populations renouncing their cars include not just the millennials that Jeff Speck cites, but Maine’s aging population as well. “At both ends of the age spectrum, people increasingly want to live near restaurants, shops, and cultural amenities.” [16] A more pedestrian-friendly Portland and pedestrian-oriented technology to accompany it would benefit multiple populations.

However, the response to the city’s varying plans to show less privilege to cars and autos is not totally positive. Portland’s plan to consolidate and shrink the Franklin arterial, thereby “[reconnecting] side streets and [improving] pedestrian and bicycle access”[17] is seen by some as a danger to the city, one that “shuts down the life blood of commerce, transit and mobility… [because] if people can’t drive here, they’ll go somewhere else.”[18] This is a serious concern to the city of Portland, which is “the financial and commercial capital of Maine.”[19] If the attempt to take cars out of Portland comes too quickly or before people are ready for it, the effects could have serious consequences for Maine’s economy.

In his lecture “The Walkable City,” Jeff Speck cites not only the enormous health benefits of walkability, but its economic, environmental, safety, and citywide benefits as well. The “inactivity borne of landscape” has more effect on obesity in America than does diet.[20] There is a direct link between the prevalence of asthma and auto exhaust emissions in urban areas.[21] The benefits of walkability are not just individual; it also fosters community and drives people to shop and buy more locally, making their communities wealthier from the inside.

And yet, the car and parking problem in Downtown Portland remains, a strain on the environment (among other things), and a major inconvenience. Apps for increased urban convenience have a large and growing market, and WalkPortland would be one of many attempts to help people navigate a city in a specific manner. The online design and tech magazine Web Urbanist ran an article listing thirteen interactive city maps, which ranged from the frivolity of a smartphone-supported citywide Pacman game called MapAttack, to the everyday usefulness of the widely popular app ParkMe, which locates open parking spots. The goal, in general, is to make the city more conveniently and easily accessible so that people can get what they want from it, when they want it. “Apps for smartphones, tablets and other gadgets are making big urban centers feel smaller than ever, making it easy to catch a ride, find cheap eats, check out street art and make new friends.”[22]

Methods

Input from actual Portland residents was immensely helpful in identifying parking as a major concern for the city, and in gauging people’s conception of the city’s size and walkability. I conducted interviews with 3 residents of Portland and 1 commuter into the city, keeping notes of how exactly they phrased their thoughts on the city. I also collected one mental map of the city from each participant. For my own perception of the city’s size and walkability, the time I spent interviewing and a transect walk to the West End were both helpful. I used QGIS to measure distances in Portland to gauge the perception of walkability against the actual distance.

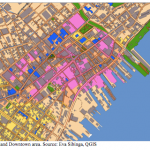

I created a simple base map of Portland, focusing on the Downtown area. I included data layers from the City of Portland that I thought would be helpful in creating a legible map for pedestrians, including of course major roads and sidewalks, but also building outlines (gray), open space (green), the boundaries of “Downtown,” (pink) historic landmarks (yellow and blue), and Metro bus routes (light blue lines). [Figure 1, Figure 2]

I concentrated on the scale of the map, and decided to keep my approach to a specific neighborhood of Portland, since my hope was to take Duany and Speck’s advice to “plan in increments of complete neighborhoods.”[23] Building outlines are an unusual inclusion in a city map, but at a pedestrian scale this seemed to make the map much more easily legible to its user. I wanted to create a map that was visually legible, appropriately scaled, and included more than just tourist attractions or sponsored locations and advertisements.

I also created a map showing the transportation network available around Portland (below). The components shown are the interstate (black), the Metro bus line (orange), the Portland Explorer tourist bus route (red), and railroad tracks (dotted black line). Once again, downtown is shown to help understand the relationship between Portland’s transportation network and its commercial center (pink). With a closer zoom, it becomes apparent that in fact Downtown is serviced more satisfactorily by Portland’s tourist bus (red) than by its city bus (orange). [Figure 3, Figure 4]

Findings

Of the four Portlanders I interviewed, three drove cars in the city. Each one of the three cited parking as source of major frustration in the city, calling it “awful,”[24] “a real difficulty” especially for those who work in Old Port,[25] and a source of dissatisfaction. Another complaint was that the city feels very much geared towards tourists, rather than residents.

Interviewees cited the small size of the city as a major upside, saying that is was “the perfect amount of city,”[26] that they enjoyed “the small town feel” and the fact that “people know you,”[27] and that the city has great, “thriving,” energy but tends to slow down by around 10 pm.[28] Each map depicted the neighborhood that the participant was most familiar with, as opposed to showing the whole peninsula or greater Portland area.

Using QGIS, I measured the length of Portland’s Downtown (as defined by the City of Portland), at .45 miles along the waterfront, and closer to .65 miles along Cumberland Avenue. The total area of the Downtown is about .25 square miles. These are all walkable distances for most adults.

Reflections / Discussion

My proposed solution is an app called WalkPortland. The app serves two main purposes. The more minor of the two is as an information source detailing where parking is available in the city. The second is as a pedestrian-oriented map application.

The parking feature of WalkPortland does not aim to make car usage and parking more convenient in Portland, or to function on a real-time basis like apps such as ParkMe[29]. While increased convenience may be a result of the app, the goal of the project is rather to have residents park their cars outside of Downtown Portland and walk to their destination, thereby reducing automobile congestion in the Downtown area (or other parts of the city) and making that a safer and more pleasant pedestrian and bicycle zone. Rather than functioning as a real-time update system for finding parking, which fosters a sense of competition and “I need to be as close as possible” that contribute to making car travel a problem in cities, the app would merely have an informational list and static map of pay lots, municipal parking and curbside parking available throughout the city. However, I anticipate that a ParkMe-like function would be highly requested.

The main focus of the app, aimed at reconnecting Portlanders’ conception of the city’s size to its actual size, is highlighted 5- and 10-minute walk radius bubbles. The goal of this feature is provide an accessible and understandable measure of Portland’s existing walkability by virtue of its scale. This will hopefully encourage people to consider walking as a viable means of transportation in the city, even across it. Using the standard average human walking speed of 3.1 miles per hour, simple calculations lead us to .25- and .5-mile radii, respectively.[30] In Portland, this translates to the entire length of the Downtown area that is walkable within 10 minutes.

Included on the app would be features important to pedestrians. Most map apps are created for car travelers and have features about traffic and toll-free routes, and leave out helpful and even crucial pedestrian information. The pedestrian map of WalkPortland would include leisure spots and amenities such as coffee shops, public restrooms, restaurants, playgrounds, grocery stores, and green space. It would also include layers that were of particular interest to pedestrian comfort and safety, such as sidewalks, street lighting,[31] public seating, bike lanes and paths, and indoor and outdoor public spaces.

To increase the accessibility of this resource so that it is not limited to those with a smartphone or an Internet connection, the maps can be made into site specific, physical, stationary maps. These maps would function the same as the app, but mapping 5- and 10- minute walk radii from their locations. These maps would serve as advertisement not only for the WalkPortland app, but also for the local businesses they would highlight. I anticipate that the primary audience for this app would be at first largely young, city-savvy smartphone users, and Portland tourists. My hope is that the app would be useful enough that anyone local might find want to have it to enhance their pedestrian experience of the city.

The WalkPortland app is an extension of existing ideas, values, and goals that the City of Portland has already set out. The app updates the technological realization of previously stated goals to help bring Portland closer to its aim of making the city more pedestrian friendly and the Downtown less congested with automobiles. Portland’s commitment to Complete Street practice and principles includes providing resources to make the pedestrian experience as pleasant and well-resourced as the driver’s.[32]

Conclusion

The WalkPortland app will help Portland drivers to get out of their cars, and it will help Portland pedestrians to get the most out of their walking experience of the city. This app will help people to think locally, and to consider walking the powerful tool that it can be in Portland. The benefits of walking are, especially in this context, manifold: to Duany and Speck this experience of the city is environmentally sustainable, community fortifying, and helpful to the literal health of the nation; to Debord, Hiss, and Grabar, the pedestrian experience of the city is of intense personal and cultural value to the city and its inhabitants; to the Portland City Council pedestrian traffic represents the alleviation of a serious congestion problem in the city’s commercial center; to Portland residents and commuters the pedestrian route is a powerful and less stressful way of understanding and moving about their city, while simultaneously helping them to engage more actively in its vibrant and thriving city life.

[1] City Council of the City of Portland ME, “Downtown Vision: A Celebration of Urban Living And A Plan For The Future of Portland – Maine’s Center for Commerce And Culture,” May 9, 1991. Accessed online December 14, 2014. http://www.portlandmaine.gov /DocumentCenter/Home/View/3376, 4.

[2] Ibid., 7.

[3] Ibid., 8.

[4] Adam Greenfield, Against the Smart City (Do projects, 2013), Kindle edition, chap. 1.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tony Hiss, “Simultaneous Perception,” in The Experience of Place (New York: Vintage, 1991), 10.

[7] Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive and Definitions,” in The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, et al. (New York: Routledge, 2014), 65.

[8] Henry Grabar, “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future of ‘Spatial Thinking’,” CityLab from The Atlantic, September 9, 2014, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.citylab.com/tech/2014/09/smartphones-and-the-uncertain-future-of-spatial-thinking/379796.

[9] Grabar, “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future.”

[10] Marina Schauffler, “Sea Change: Living without cars a good sign of the times,” Portland Press Herald, November 3, 2014, accessed December 15, 2014, http://www.pressherald.com/2014/11/03/sea-change-living-without-cars-a-good-sign-of-the-times.

[11] Andres Duany and Jeff Speck, The Smart Growth Manual (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010), 168.

[12] Duany and Speck, The Smart Growth Manual, Appendix 1.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Sarah Marusek, Politics of Parking: Rights, Identity, and Property (Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2012), 30.

[15] Ibid., 32

[16] Schauffler, “Sea Change: Living without cars a good sign of the times.”

[17] Kelly Bouchard, “Opportunity, concern seen in Portland’s plan for Franklin Street,” Portland Press Herald, October 1, 2014, accessed December 15, 2014, http://www.pressherald.com/2014/10/01/opportunity-concern-are-seen-in-arterial-plans.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Jeff Speck, “The Walkable City” (Ted Talk, TEDCity 2.0, September 2013) Accessed online December 14, 2014, http://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_speck_the_walkable_city?language=en, 7:35

[21] ibid., 12:41.

[22] Steph, “Urban Apps: 13 Interactive City Maps, Tools & Guides,” Web Urbanist, accessed December 15, 2014, http://weburbanist.com/2013/07/15/urban-apps-13-interactive-city-maps-tools-guides.

[23] Duany and Speck, The Smart Growth, Appendix 1.

[24] Josh (26, Portland resident), interview by Eva Sibinga, October 13, 2014.

[25] Brittney (23, Hollis, ME resident), interview by Eva Sibinga, October 13, 2014.

[26] Josh, interview.

[27] Brittney, interview.

[28] Marina, (22, Portland resident), interview by Eva Sibinga, October 13, 2014.

[29] www.parkme.com

[30] http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/Walking.html

[31] This idea came from Eileen Johnson, Lecturer in Environmental Studies at Bowdoin College.

[32] City of Portland. Council Order 125, “Complete Streets Policy,” December 17, 2012. Accessed online December 16, 2014. http://www.smartgrowthamerica.org/ documents/cs/policy/cs-me-portland-policy.pdf.

Bibliography

Bouchard, Kelly. “Opportunity, concern seen in Portland’s plan for Franklin Street.” Portland Press Herald, October 1, 2014. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/10/01/opportunity-concern-are-seen-in-arterial-plans.

City of Portland. Council Order 125. “Complete Streets Policy,” December 17, 2012. Accessed online December 16, 2014. http://www.smartgrowthamerica.org/ documents/cs/policy/cs-me-portland-policy.pdf.

Debord, Guy. “Theory of the Dérive and Definitions.” In The People, Place and Space Reader, edited by Jen Jack Gieseking, William Mangold, Cindi Katz, Setha Low and Susan Saegert, 65-69. New York: Routledge, 2014 [1958].

Duany, Andres, and Jeff Speck. The Smart Growth Manual. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Grabar, Henry. “Smartphones and the Uncertain Future of ‘Spatial Thinking.” CityLab from The Atlantic, September 9, 2014. Accessed September 15, 2014. http://www.citylab.com/tech/2014/09/smartphones-and-the-uncertain-future-of-spatial-thinking/379796.

Greenfield, Adam. Against the Smart City. 1.3 edition. Do projects, 2013. Kindle edition.

Hiss, Tony. “Simultaneous Perception.” In The Experience of Place. 3-26. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Marusek, Sarah. Politics of Parking: Rights, Identity, and Property. Burlington: Ashgate Publishing Ltd, 2012.

Shauffler, Marina. “Sea Change: Living without cars a good sign of the times.” Portland Press Herald, November 3, 2014. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://www.pressherald.com/2014/11/03/sea-change-living-without-cars-a-good-sign-of-the-times.

Speck, Jeff. “The Walkable City.” Ted Talk, TEDCity 2.0, Filmed September 2013. Accessed online December 14, 2014. http://www.ted.com/talks/jeff_speck_the _walkable_city?language=en.

Steph. “Urban Apps: 13 Interactive City Maps, Tools & Guides.” Web Urbanist. Accessed December 15, 2014. http://weburbanist.com/2013/07/15/urban-apps-13-interactive-city-maps-tools-guides.