Mobilizing v. Organizing? Which Would Have Worked Better?

The initial group of students who approached the issue would be a prime example of what mobilizing looks like. As explained by Jane McAlevey, mobilizing is the act of gathering people who already agree with you to act. In this instance, the students resorted to their peers from an organization that shared the same goals and ideologies they were all members of. While this is a great start, as explained by McAlevey, this can limit their outreach.

Essentially, the base of people that they are trying to reach will not be substantially expanded to networks that may not be on the same page but could be potentially persuaded and join the movement. Instead, the youth involved should have begun their strategy with mobilizing and eventually transition to organizing. In this capacity, the students would mobilize amongst themselves to build a foundation and then switch to an organizing approach to expand their crowd of support.

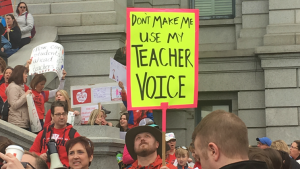

Where Y’all Teachers At When We Need You? Seriously…

Although the work done by these students was brought to the administration, I believe it would have progressed further if teachers became involved. As noted by Benson, educators in urban schools, such as Deering High School, must take the time to become fully aware of the scope of issues around inequity at their school. While the students of these teachers were mobilizing around their cause, educators should have been collaborating with them on an action plan to address the problem immediately.

In this capacity, both students and teachers would have been able to form a partnership—one that would later develop into a stronger, more united front. Essentially, these educators are responsible for nurturing their students’ voices and responding to their efforts by amplifying their call to action.

Stronger Together

Furthermore, Mariana Angelo’s efforts reflect many of the organizing strategies McAlister and Catone underscored in their article. As discussed by both authors, Mariana essentially “prioritize[d] the development of leadership among parents and community members” (McAlister and Catone). When she was actively educating parents, she was empowering them. Even if they may not have had the language to relay what they wanted to say, they were equipped with more knowledge, and from this, they were able to find the strength to mobilize. Further, Mariana succeeded in her mobilizing efforts because she was connected to the community she was trying to advocate for. For her, this was not a distant issue—its impacts were felt all around her.

Final Note

I wanted to end this discussion section with a quote by Christopher Emdin, the author of “For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood… and the Rest of Y’all Too: Reality Pedagogy and Urban Education.” In his book, he discusses a method of teaching he refers to as “reality pedagogy.” He writes:

“Instead of seeing the students as equal to their cultural identity, a reality pedagogue sees students as individuals who are influenced by their cultural identity. This means that the teacher does not see his or her classroom as a group of African American, Latino, or poor students and, therefore, does not make assumptions about their interests based on those preconceptions. Instead, the teacher begins from an understanding of the students as unique individuals and then develops approaches to teaching and learning that work for those individuals” (Emdin 27-28).

I wanted to take a moment to reflect on the heart of the issue and use this quote as a sort of an ode to teachers working in urban schools. The message in this quote should frame the way teachers engage with students who speak a second language and may be struggling with the English language. Educators should not solely view students by their ELL identity, but rather, as complex learners who have individual needs.

Further, what must be understood is that teacher attitudes towards their students motivate teacher behavior in the classroom, and consequently, impact student achievement. If teachers harbor the genuine belief that their students—regardless of the obstacles that might present themselves—are capable of success, then they will be more prone to make deliberate adjustments to their curriculum to improve the quality of learning for ELL students in the ELL and mainstream classroom.

In essence, educators need to take risks in their academic approach and need to match their students’ daring attitude—particularly the ones mobilizing around them. Simply put, comfort and compliance will benefit no one.