When student organizers seem to operate independently of any visible, larger organization, their work can be linked back to the liberatory organization framework espoused by Pablo Freire and the youth empowerment organizing framework elucidated by Ben Kirschner.

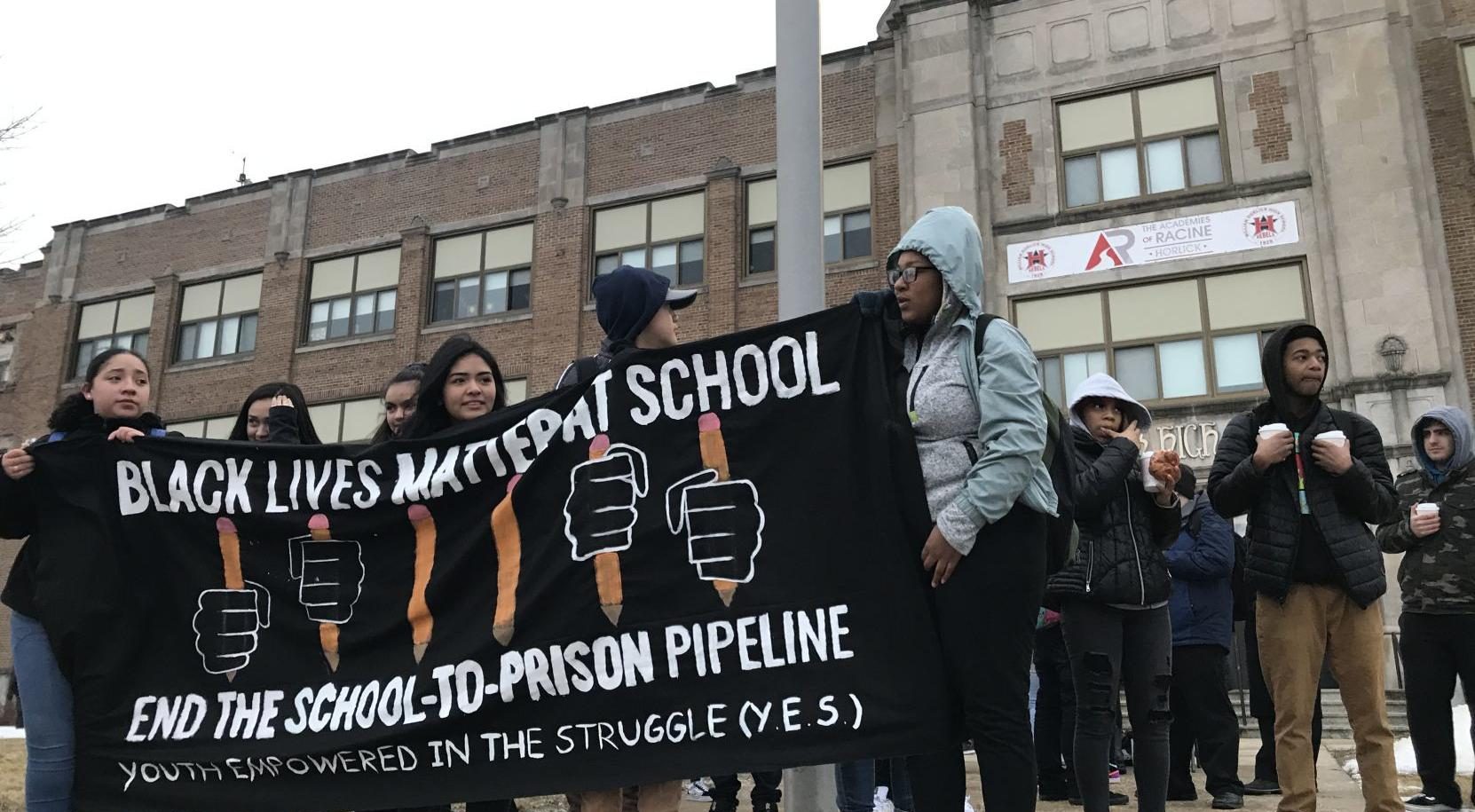

Student organizing follows a Freirian method when organizers try to connect with their members’ personal experiences and, as a result, earn more engagement from their members  (Martinson and Su 2012). In Minneapolis, we can see student-organizers taking this approach with students organizing protests that fight against policing in schools by relying on personal experience with policing to encourage broader support for the protest and to apply more pressure on the school board (Retta, 2020). Furthermore, Freirian organizing tends to de-emphasize the importance of leadership positions by seeking to abolish traditional student-teacher hierarchies (Martinson and Su, 2012). This aspect of Freirian organizing is very present in Minneapolis as students who seem to be leading protests do not actually have an affiliation with any larger organizations, such as teacher unions, the PTA, or national organizing groups. Rather, student organizers who take on some leadership role seem to be functioning more as democratic participants who happened to be interviewed. While it is very clear that student pressure had an impact on swaying the mind of the school board to cancel the contract with the Minneapolis Police Department, it remains unclear exactly who the student leaders of the movement are, strongly suggesting that student organizers in Minneapolis are not following traditional hierarchies.

(Martinson and Su 2012). In Minneapolis, we can see student-organizers taking this approach with students organizing protests that fight against policing in schools by relying on personal experience with policing to encourage broader support for the protest and to apply more pressure on the school board (Retta, 2020). Furthermore, Freirian organizing tends to de-emphasize the importance of leadership positions by seeking to abolish traditional student-teacher hierarchies (Martinson and Su, 2012). This aspect of Freirian organizing is very present in Minneapolis as students who seem to be leading protests do not actually have an affiliation with any larger organizations, such as teacher unions, the PTA, or national organizing groups. Rather, student organizers who take on some leadership role seem to be functioning more as democratic participants who happened to be interviewed. While it is very clear that student pressure had an impact on swaying the mind of the school board to cancel the contract with the Minneapolis Police Department, it remains unclear exactly who the student leaders of the movement are, strongly suggesting that student organizers in Minneapolis are not following traditional hierarchies.

Significantly, student organization on the ground in Minneapolis clearly includes Krischner’s two markers of youth empowerment activism: attempts to overcome the stereotype of the naive youth and resemblance to non-traditional educational environments. Under the framework of youth empowerment activism, youth organizers seek to buck public conceptions that youth are neither sophisticated nor developed enough to participate in or shape public policy (Krischner, 2008). With thousands of students both signing petitions to remove SROs from schools and taking to the streets with daily protests over the over-policing of minorities, Minneapolis youth sought to pressure and shape public policy on these issues despite their position as students (Retta, 2020). Furthermore, youth organizers often learn to protest for these policy changes in environments resembling non-traditional educational environments, such as students learning how to take action to solve meaningful and concrete problems instead of grappling with the transactional and abstract nature of problems presented in traditional education (Kirschner, 2008). Student protesters in Minneapolis regularly connected their organizing struggles back to their own struggles with SROs, SLOs, or with the outside police and, in the process, learned how to propose policy modifications and exert pressure on the school board to get the result the students desired. Thus, these two frameworks of student organizing suggest how student organizers succeeded to accomplish most of their goals despite the seeming lack of institutional support.